A previous version of this essay was published in City Unsilenced: Urban Resistance and Public Space in the Age of Shrinking Democracy, ed. Jeffery Hou and Sabine Kneirbein (New York: Routledge, 2016).

Foucault asserts that genealogy differs from history in that it identifies the accidents, deviations, errors, false appraisals, and faulty calculations that gave birth to things that have value to us. This is in contrast to demonstrating a historical past to actively exist or animate the present in some essential, predetermined form.1 This insight of Foucault’s bears particular relevance to the history of cities, in that laws, plans, and projects often have results and afterlives that defy stable intentionality as they produce new practices and spatial forms.

This concept of genealogy provides a framework to review the urban activism practiced by Land Action, a legal aid skill-share based in Oakland, California, dedicated to utilizing and teaching “adverse possession law” (the legal procedure for acquiring property through squatting). One point to begin this genealogy is the Occupy movement of 2011. While occupiers in New York City’s Zuccotti Park gained media prominence, on the other side of the country, occupiers in Oakland, California, also garnered national attention for their radical actions, including the dramatic closure of the Port of Oakland. Lesser-known actions included attempts to permanently occupy vacant buildings in downtown Oakland, leading to pitched battles with the police and a proliferation of political squats across the city. This is the context that gave form to Land Action in its efforts to reclaim properties left vacant from decades of racialized disinvestment and fiscalized urban development. However, long before Land Action, squatting developed as a spatial practice that was pivotal to settling the San Francisco Bay Area and the US West. Since Land Action’s current endeavors spring from these genealogical accidents, understanding them is crucial not only for understanding Land Action’s practice but also for making second-order observations about unforeseen pitfalls, potential outcomes, and new alternatives within this contemporary practice.

Settler-Colonialism and the Land Question

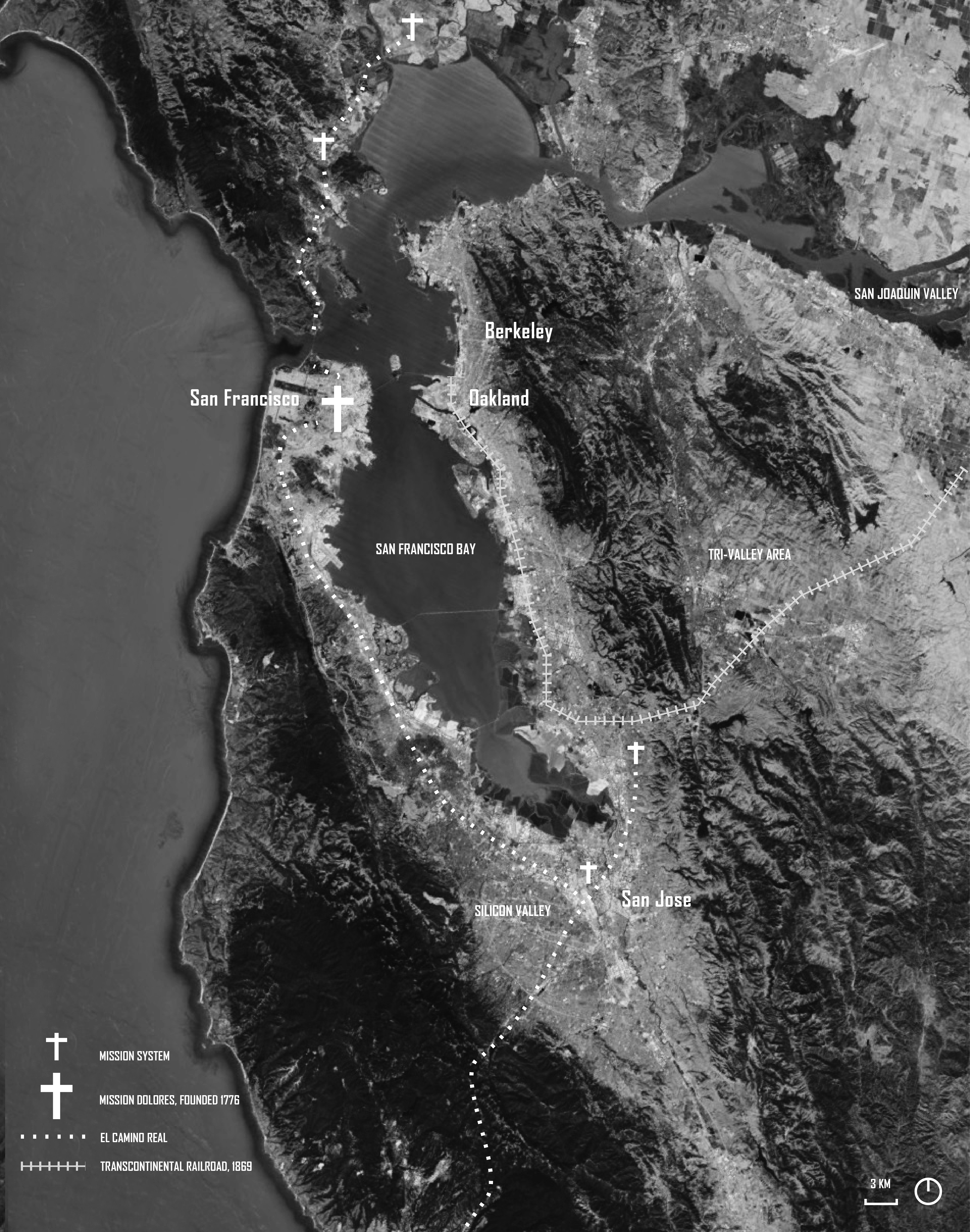

Spanish imperialism organized space in New World settlements into three separate formations according to the Law of the Indies: a Presidio military installation, an ecclesiastical Mission, and a Pueblo, the civilian town where the Law of the Indies drew upon Leon Battista Alberti’s Renaissance interpretations of Vitruvius’s ancient Ten Books of Architecture to establish the grid form around a central plaza, which persists in towns and cities along the West Coast. In the puebla of Yerba Buena, for example, the Law’s guidelines designated public spaces for pasturing livestock and trade goods centered on modern-day Portsmouth Square in San Francisco. This partitioning of space according to enlightenment principles established sacred and secular space that laid the way for regimes of private property. The ecclesiastical doctrine of the Mission bundled this spatial partitioning with the establishment of a white supremacist settler-colonial racial hierarchy.2

With the decline of Spanish mercantilism, the church’s role as primary arbiter of land and labor in California came to an end. By the 1800s, the Spanish crown began to secularize the missions and granted large tracts of land to Californio ranchers. However, only twenty-five years after Mexico achieved independence, the Mexican-American War broke out over a land dispute with the newly annexed state of Texas as the United States expanded westward along the frontier. By the war’s end, the US occupation was made official, with Mexico ceding the territories of modern-day California, New Mexico, and other large chunks of the West in exchange for the meager sum of $15 million. At this moment, the distribution of this territory—known as “the land question”—reflected broader conflicts stemming from immigration and slavery, upon which the future of the West and Jeffersonian democracy appeared to hinge, especially after gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in 1848. Would land be distributed to the (white male) landless citizenry centered in the urbanizing eastern cities? Or granted to large corporations employing noncitizen labor following the plantation model of the US South and Caribbean? Revisiting these questions helps frame a review of the contemporary politics of Land Action’s work. In the end, land outside the municipal boundaries of the old pueblos or unaccounted for in arcane Spanish records became “public domain” eligible for settlement by white men according to the Preemption Act of 1841. This federal act of Congress, passed a few years before the start of the Mexican-American War, outlined, legalized, and encouraged the practice of squatting as a mechanism to settle America’s newly acquired western territories.3

Squatting practices illustrated the paradoxical notion of a “public domain,” one that was pivotal for a democratic society yet restricted to a privileged set of white freemen. In both the East Bay and San Francisco, these dynamics continued in the formation of the modern metropolis and the process of enclosure, or what Marx calls ursprüngliche Akkumulation, that paves the way for industrial capitalism. Squatters, for example, were integral to the creation of San Francisco’s famous Golden Gate Park in the 1860s. While city officials argued that the land was part of the Spanish pueblo and therefore within the jurisdiction of the City of San Francisco, prominent and politically influential squatters in the area argued that they occupied federal lands subject to the Preemption Act of 1841. After protracted litigation over the location of the new park, the Outside Lands location was chosen to suit the mutual interests of both the squatters and the city. Prominent squatters agreed to donate their claims to portions of land to the city for what was to become Golden Gate Park in return for receiving a clear title to their remaining homesteads. As was foreseen with the construction of the park, the value of their remaining property spiked dramatically. The city, for its part, rather than constructing a park in the crowded tenements where land was more expensive, managed to acquire cheap land for a municipal public space that extended the boundaries of San Francisco all the way to the Pacific.4

After the wars of the early twentieth century, a selective, racialized democratization of land through privatization continued with the GI Bill, the interstate highway system, and redlining and blockbusting financial schemes as urban development exploded outward across the hills in a process Kenneth Jackson famously described as “the crabgrass frontier.”5 As this growth slowed in the late 1970s and the real estate market in California began to suffer heavy inflation, retirees concerned about paying property taxes on a fixed income initiated a referendum officially named the “People’s Initiative to Limit Property Taxation” (Proposition 13). By freezing property taxes at their 1975 value with a hard cap on interest until the property is resold, Prop 13 served to permanently skew the real estate market, locking in a predominantly white landed class—which had already benefited from the wartime boom and postwar prosperity—into paying a disproportionately low property tax into perpetuity. Prop 13 effectively ended an era of progressive planning that helped build the infrastructure of twentieth-century California, as local governments, losing a major source of revenue, became beholden to block grants from the state government.

But beyond decimating public services, it had the unintended spatial consequence of fiscalizing land use. Rather than balancing modernist planning criteria such as housing, work, circulation, and recreation, Prop 13 reflects a neoliberal or entrepreneurial shift in spatial planning whereby tax-earning assets (such as retail shopping centers that generate sales tax revenue) are given preference. Subsequently those that do not generate income, such as working-class family housing that demand funds for public schools, are relegated to distant in-land areas desperate to attract the most meager development.6 Further, it creates disincentive to sell property post–Prop 13, since the sale of a property results in reassessing property taxes, creating severe bottlenecks in the housing delivery system thereby restricting access to land.

This reflects a crucial shift in regional urban dynamics that are vital to understanding the landscape in which Land Action operates. As urban geographers Richard Walker and Alex Schafran describe it, the present-day Bay Area—much like Los Angeles, its sprawling rival to the south—is characterized by a polycentric network of vast suburban sprawl.7 Generally speaking, the flatlands ringing the bay were traditionally the most densely populated and industrialized, where the working classes occupy the oldest housing stock. These areas struggled in the wake of post-Fordist restructuring while San Francisco evolved into a center for finance, tourism, and increasingly a sort of “urban lifestyle suburb” for the economic engine of the region: Silicon Valley. With San Francisco becoming the bedroom community for Silicon Valley, cultural industries and nonprofits have been displaced to Oakland—the “new urban frontier”—and gentrification creeps across the Bay. West Oakland, a historically black area that witnessed systematic disinvestment and under siege during the war on drugs of the 1980s and 90s, has gradually come to be appreciated for its Victorian housing stock, multicultural diversity, and ten-minute nonstop train ride to downtown San Francisco. However, residents priced out of San Francisco and the flatlands of Oakland, often surviving on a service-industry wage, are increasingly forced to relocate to suburbs of the San Joaquin Valley, sometimes upward of 100 miles from San Francisco. Because this low-wage housing stock generates so little in property taxes due to Prop 13 urban restructuring, these areas often lack basic amenities and infrastructure. The subprime mortgage crisis of 2008 accelerated this process, especially for working-class families in the gentrifying flatlands ringing the bay and the far-flung suburbs of the valley. These are the conditions into which Land Action intervenes, extending on the tradition of squatting practices and culture in the San Francisco Bay Area and serving as an agent of protest in the face of an extreme housing shortage and rising economic inequality.

Land Action and Contemporary Occupations in the San Francisco Bay Area

Rooted in the East Bay’s punk culture, Land Action founder Steven DeCaprio became acquainted with squatting while on tour with his band in 1999, performing at squats across Europe, notably La Scintilla in Modena, Italy. By the time DeCaprio returned to the Bay Area he found himself homeless, and after several years navigating the dizzying legal process and an arrest for trespassing, he successfully defended his own residence at an abandoned duplex in Oakland. As DeCaprio legally and structurally secured the occupation, he came to be considered by many an expert on squat law and adverse possession, and his house served as a sort of headquarters for Land Action and a material depot while the group organized with other squatters in the area. Once Occupy Oakland began, it served as a platform to expand Land Action as a skill-share network, where occupiers would exchange tactical and legal knowledge, contributing their own skills and labor in the many efforts required by occupying buildings left vacant and disintegrating by racialized economic restructuring. Dicaprio delivered presentations at Occupy Oakland on occupying buildings with the goal of providing permanent space to activists and organizers from Occupy Oakland.

Through trial and error, Land Action attempted to design a process to systematically deploy adverse possession as an act of protest. Land Action’s current process begins with site selection, researching tax-defaulted property auction listings or inquiring with government officials on the legal and financial status of other prospective sites. Once a prospective site is selected, physical, and spatial qualities such as presence of buildings or quality of the soil become important indicators for the possible use of the site and the potential for signifying its “improvement,” while the location of the sewer lateral might dictate the placement of additional structures such as a “water house” with shared kitchen and bathroom. Land Action’s squats have often required major cleanup upon entrance: DeCaprio has noted that many of his squats have been initially full of debris and dead animals. Major impediments to taking action can include intimidation from police or red tape from municipal officials in acquiring building permits. To anticipate these obstructions, Land Action deploys structures with a maximum footprint of 11.15 square meters, spaced 15 meters away from each other—just under the threshold for a building permit in California. An occupant can be evicted at any time, especially in the early stages, so inexpensive and modular designs that can be easily and cheaply constructed using commonly salvaged or off-the-shelf materials and hand tools are ideal. DeCaprio also espouses the ideals of sweat equity: once a squat has been secured, Land Action initiates a number of home improvements to its squatted properties, including installing drywall and new floors. In one squat in particular where DeCaprio resides, DeCaprio installed solar panels on his roof and remains off-the-grid.

As Land Action physically secures an occupation, they create a paper trail to the property by paying back taxes, which will name Land Action on the assessor’s tax roll, filing a homestead declaration that recognizes the property as the primary residence of the occupier. DeCaprio has found that as this paper trail of innocuous bureaucratic requests snowballs, the occupation becomes more secure as claimants will require lengthier legal proceeding to win evictions and therefore become more willing to negotiate with occupiers.

In many respects, these tactics intersect with the “Tiny Home” or “Small House” trend that is popular in the largely affluent northern reaches of the Bay Area. Following this typology, a well-designed small dwelling can function to activate the landscape and utilize it as an exterior dwelling space in the moderate California climate. However, in contrast to the Thoreau-inspired dogma prevalent in the Tiny House movement and the self-sufficiency of homesteading squatters in the nineteenth century, occupying urban land means working with people, building coalitions, and commons. Following this understanding that spatial politics—especially in Oakland—cannot be reduced to building codes, Land Action developed an urban micro-farms project to better navigate the social dynamics of occupying urban land.

Urban Micro-Farms

Like the Occupy movement rousted from Oscar Grant Plaza, a subsequent wave of post–Occupy Oakland squats encountered mutually exclusive assertions of rights rooted in cultural conflicts between publics and counterpublics. Land Action faced difficulty coordinating with occupiers and reciprocating on the skill-share, which in part stemmed from the lack of a cohesive structure at many of the occupations. In the worst cases, individuals or groups of individuals would strong-arm their way into an occupation, what DeCaprio would call “squatting a squat,” ultimately leading to conflicts at numerous squats in Oakland, including the “Hot Mess” Squat, which was rendered uninhabitable due to severe fire damage in the spring of 2014. These dynamics caused Land Action to shift its focus from traditional housing squats to the creation of urban micro-farms in vacant lots around Oakland produced by the city’s anti-blight campaign that demolished run-down tax-defaulted properties.

The urban micro-farm project tapped into existing community gardens, sustainability politics, and slow and local food movements sweeping the country, which already had a strong presence in the Bay Area. Many in Land Action felt gardening made the organization more broadly appealing than squatting vacant buildings, which was associated with Occupy Wall Street, vandalism, riots, and violent clashes with the police. While squatters generally viewed community gardening as volunteerism and therefore unsustainable in the long-term outside of those with disposable time and income, the micro-farming project incorporated housing into the action. Adopting a stewardship-housing model for individuals or small groups of people also bypassed the long-term social difficulties presented by squatted buildings. The idea was that these individuals or smaller collectives would be bound to the land, working it as required by the adverse possession process, with legal support from Land Action. Following this model, Land Action even reached an agreement with the city of Oakland in which Northern California Community Land Trust could take ownership of the land once it was ushered through the adverse possession process, legalizing the occupations. Because of the Land Trust’s stewardship mission, adverse possession emerges as a means to de-commodify land through the labor of occupation, ideally a sort of reverse settler-colonialism that returns it to the commons rather than enclosing it as private property as in the days of the frontier.

However, significant hurdles remained as occupiers turned to green and sustainability politics in their desire to distance themselves from the radical politics and racial divisions of Occupy Oakland. A summer crowdfunding campaign was not as successful as hoped, likely due to the fact that a localized community garden project with no connection to broader political resistance failed to resonate beyond immediate Bay Area gardeners and local food advocates. Worse, soliciting donations under the banner of “a garden on every corner” replicated the colonial ideology of “improvement” and risked appearing obtuse to the reality of displacement in the context of extreme gentrification—particularly given the fact that many of these lots once contained multiple housing units prior to the city’s racialized blight elimination programs. While an apolitical sustainability approach saved Land Action gardens from displacement by city authorities, it offered little aid to the very real fears of neighbors who may view tiny homes sprouting up on abandoned lots as harbingers of gentrification. Like the broader Occupy movement, Land Action is not a black-led group of multigenerational West Oaklanders but a hodgepodge anarchistic affinity group, a heterogeneous mix of racial and class backgrounds but broadly leaning toward queer, punk youth. This perceived or presented identity can place Land Action outside of the predominantly black West Oakland community’s established political hierarchies and social institutions, allowing power brokers to prevent occupations or other challenges to entrepreneurial urban development. The group clashed with Elaine Brown, former leader of the Black Panthers, as well as local clergy and investors looking to cut deals with the city on undeveloped property in West Oakland. In February of 2016, the Alameda County district attorney cracked down on one of Land Action’s occupations, charging not only the occupiers but DeCaprio and another organizational board member with felony, conspiracy, and fraud crimes; he and three other group members now face up to eight and a half years in prison. DeCaprio believes these charges to be politically motivated, stemming from his dispute with the California State Bar Association’s refusal to grant his law license over issues of “moral character.” While these charges are serious, the case has been taken up by well-known Bay Area civil rights attorneys, including Tony Serra, and thereby presents an opportunity to publicly contemplate the state’s response to a contemporary crisis of housing and access to land.

While the conflicts of the Old West lie in the past, their afterlives continue to animate contestations around land in California in new ways. Racial hierarchies stemming from colonization and the imposition of property regimes continue to resonate in California urban politics. First deployed as a mechanism by the state to settle and improve western territories with excess white landless laborers, the work of Land Action shows the potential for a reappropriation of legal codes and social structures to democratize access to land without speculative financial instruments. However, when squatting and urban gardening become an end in itself, the dynamics of enclosure of the western frontier by a privileged class are reproduced on the new post-industrial urban frontier described by Neil Smith.8 Detached from an overarching framework for connecting individual and actions to the broader dynamics animating contemporary space, little differentiates these occupations from the nouveau city beautiful “parklets” popping up in front of cafés in gentrifying neighborhoods. As Jeffrey Hou argues, neither formal public spaces nor symbolic cultural inclusion is sufficient to challenge the commodification of social relations as a result of fiscalized spatial planning.9 Gestures toward neighborhood greening or institutionalized multiculturalism, hollowed of demands for material redistribution and communal control outside the market, will not solve the problem of a 100-mile commute from underdeveloped San Joaquin Valley and may even accelerate gentrification by increasing the cultural capital of a given place. Reviewing Land Action’s work in the context of the broader genealogy of squatting in California reveals how designers and urban planners must think critically about the distribution of value produced in the everyday occupation of space. This means challenging not only landlordism and regimes of private property but also the slippery effects of cultural and social capital in an age of environmental gentrification. Such inquiry can lead not only to more vibrant public spaces, a prime goal of planners and designers, but to a more equitable society as well.

-

Michel Foucault, Language, Counter-Memory, Practice (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1980). ↩

-

Lisbeth Haas, Conquests and Historical Identities in California, 1769–1936 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995). ↩

-

William Wilcox Robinson, Land in California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1948). ↩

-

For the prehistory of Golden Gate Park and the Outside Lands, see Terence Young, Building San Francisco’s Parks, 1850–1930 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004); and Raymond H. Clary, The Making of Golden Gate Park: The Early Years, 1865–1906 (San Francisco: California Living Books, 1980). ↩

-

Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985). For the politics of this spatial transformation in Oakland, see Robert O. Self, American Babylon: Race and the Struggle for Postwar Oakland (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005). ↩

-

Alex Schafran, “Origins of an Urban Crisis: The Restructuring of the San Francisco Bay Area and the Geography of Foreclosure,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 37, no. 2 (July 2012): 674. ↩

-

Richard Walker and Alex Schafran, “The Strange Case of the Bay Area,” Environment and Planning A, vol. 47, no. 1 (2015): 10–29. ↩

-

Neil Smith, The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City (New York: Routledge, 1996). ↩

-

Jeffrey Hou, “Beyond Zuccotti Park: Making the Public,” Places Journal (September 2012). ↩

Millay Kogan is a graduate of Cornell University (BS), Columbia University (MS Urban Planning), and Golden Gate University School of Law (JD). She has worked in international development, housing, and environmental law, and currently resides in Los Angeles.

Marcus Owens is founding partner of CAMO design studio in Oakland, California. He is currently a PhD candidate at the University of California–Berkeley. Previously, he studied architecture and urbanism and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and Harvard Graduate School of Design.