I fondly recall a mid-1990s lecture by Deborah Berke praising the possibilities of “everyday” architecture, arguing that visual fireworks were not necessary for success as an architect (or, I imagined, as an architecture student).1 This has proven true enough, at least for me: I have great respect for projects of modest budget and scope, in which typical materials and trades are used with creativity to meet clients’ and users’ needs. Even absent creativity, I’ll grant that architects, like 99 percent of everyone, have to make a buck—both for their survival and for the survival of the profession under today’s conditions. Architecture can be driven as much by constraints as by program, digital tools, or higher aspirations.

At first glance, the San Quentin Lethal Injection Chamber (constructed 2007–10) might be just such an “everyday” project of the kind that Berke discusses, driven by basic constraints and implemented without much fanfare—although her concern for thoughtful selection, placement, and proportioning of everyday materials is not much in evidence here.2 Painted sheetrock walls, resilient flooring, vinyl cove base, and fluorescent lighting are used in a thoroughly predictable and pedestrian manner, much like a dentist’s office in a strip mall. The buttresses of the adjacent prison housing block, which a more creative designer might have incorporated, are instead covered by new framing; a storage room is used to occupy one of these irregular alcoves. But there is more to this design than meets the eye. Sometimes the banal is not ordinary.3

The design constraints here were not the typical budget and schedule but instead flowed from a court decision in 2006.4 Prior to the court’s intervention, the State of California had conducted executions in a small suite of rooms centered on an airtight steel capsule designed for executions by lethal gas. When gas was replaced by lethal injection as a presumably more humane method of execution, the state simply crammed a gurney into the gas chamber. This created cramped working conditions and poor sight lines for the execution staff that eventually became part of a finding of constitutional violations that temporarily suspended the death penalty in California (another finding was that the level of pain experienced from the lethal injection was not necessarily humane). In order to ensure that the condemned man dies without a “cruel and unusual” level of pain, the judge ruled, the state’s executioners must carefully observe him (or very rarely her) for signs of the effectiveness of the anesthetic and evidence of death—something impossible to do through the limited windows of the old gas chamber.5 In addition, the number of people watching the execution—in their respective roles as official witnesses, media representatives, state agents, family members of the victim, and the inmate’s spiritual advisers and visitors—were creating crowding that obstructed “even simple movement,” according to the judge.6

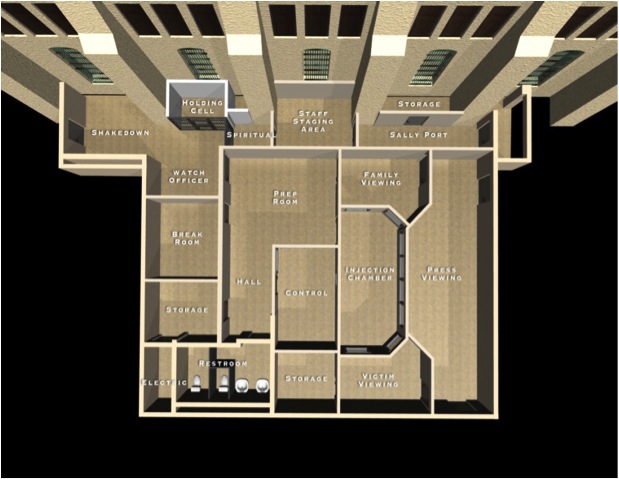

The state’s response (in addition to changing more prominent aspects of the lethal injection protocol such as the rules for handling the drugs involved) led to plans to build an all-new facility for lethal injection that would provide more workspace around the body of the condemned man, an adjacent secure workspace and chemical storage room, and separated viewing areas for the various categories of observers. Site constraints included a law requiring all executions in the state to be carried out at San Quentin State Prison—the oldest and most complicated facility in a sprawling thirty-three-campus prison system, relatively close to the federal courthouse in San Jose—which precluded building on a less heavily scrutinized and crowded prison campus. Bureaucratic skullduggery initially led to an unrealistically low project budget of $399,000: just under the $400,000 requirement to request legislative authorization of the project.7 Perhaps some secret executive-branch projects stay secret; in this case the state legislature found out about the project, causing further delays (they weren’t happy about having been hoodwinked) and an eventual approved budget increase to over $850,000. This included the use of inmate labor provided by the California Department of Rehabilitation and Corrections (CDCR) vocational training program.

The general layout of the suite of rooms was borrowed from previously completed projects in other states. Unlike in other states, where death chamber design materials are generally only available when they have been released in response to lawsuits, the final project was presented on a tour that included the federal judge presiding in the case, reporters, and a press release that included output of the CAD model used to design the project (now no longer available). Still, when I made a public request for the identity of the architect(s) and engineer(s) responsible for the project, CDCR would not provide an answer.

The Lethal Injection Chamber is a project that teeters on the edge of visibility and invisibility. CDCR exercised unusual control of the project budget in order to try to keep the project invisible. Yet a floor plan of the design proposal eventually became part of the court record submitted by CDCR to prove the constitutionality of the new facility, making it permanently available to the public. Newspapers published photos of the completed chamber and ancillary spaces and developed infographics of the layout.8 Nevertheless, today it is an incredibly difficult space for members of the public to visit unless they are part of the highly specified group of participants in or observers of an execution.

Perhaps in the same spirit, or perhaps because of the general obsession with the control of sight lines in prison environments, visibility within the Lethal Injection Room itself is carefully controlled.9 Witnessing the death of the condemned man is a central component of the execution ritual, with prescribed access for family members of the condemned man, family members of the victim, prison staff, and witnesses to verify that vengeance has been earned for the aggrieved public. Accordingly, the execution room is something of a fishbowl, surrounded on all sides by windows, including a band of wall-to-wall glazing for the public witness and media viewing room. However, mirrored glass is used along the line where the victim’s family might see the inmate’s family: a line that crosses the body of the condemned man, as the two families are positioned at opposite ends of the room just as they are presumed to be of opposite sympathies regarding the murder. Although it is not uncommon for the family of the victim in capital cases to object to the execution of the perpetrator, either out of a generalized objection to killing or after personal reconciliation, the plan denies the opportunity for this kind of potentially healing contact between families. Just as positions of state-driven authority are fixed in a courtroom, with a jury one level up and the judge above them, the dichotomous relations of innocent and guilty inherent in the finality of the death penalty are fixed around the body of the condemned man.

The position of the “lethal injection team” is even more tightly prescribed. California’s new regulations detail which of the various execution subteams will occupy different rooms, and when individual members will enter or leave them. A small, one-way-mirrored window and four hose ports connect the intravenous subteam, who insert the IV lines into the condemned man after the security subteam has brought him into the injection room and strapped him down, and the infusion subteam, who push the lethal chemicals through syringes in the Infusion Control Room behind the condemned man’s head. 10 Visibility is required for direction of the infusion subteam by the warden stationed in the injection room, but the mirrored glass protects the infusion subteam members from identification from the press gallery opposite. The hose ports, arranged in a roughly cruciform pattern, carry the IV lines that connect the syringes in one room to the condemned man’s veins in the other. Yet even though these ports are among the few indicative details that stand out from the banality of the overall project, they are not particularly uncommon objects; I, myself, specified through-wall hose ports in a winery project (stainless steel, as opposed to the plastic used here). The most obvious signal of the room’s function, the lethal gurney, is on wheels—as if the space might be used for other purposes.11

Hannah Arendt famously diagnosed the “banality of evil” after watching the trial of Adolf Eichmann, a midlevel bureaucrat who was part of implementing the mass deportation and execution of European Jews in the Nazi Holocaust. The banality of California’s execution chamber is just as troubling as if it were a Gothic Revival chamber of horrors or a dystopian stainless-steel science fair project. The use of everyday materials indicates the lack of special value that the state of California places on its practice of execution. But execution is not an everyday procedure, nor does it happen in an everyday place. In ancient and medieval times, and even in the early history of the United States, executions took place in venues of major ritual significance; part of execution’s role was to reinforce the authority of the state against potentially lawless and disorderly subjects—even though, as Foucault observes in Discipline and Punish, the occasion of an execution itself predictably triggered disorder and lawlessness if not rioting.12 The refusal of many American states to place the lives of people above their own authority is a troubling aspect of US jurisprudence that human rights organizations around the world routinely denounce, and that other countries have demonstrated they can live without. As Amnesty International and other critics observe, the death penalty says far more about whose death is worth revenging (and about persistent American attitudes toward race) than about the value of life: More than three-quarters of executions are for the killing of white people, even though black people constitute almost half of all homicide victims.13

The death penalty debate, especially in California, now hangs on a tenuous balance between the desire for revenge (an “eye for an eye”) and revulsion at the spectacle of suffering driven by our own blood lust (with a subtext of racism). CDCR—the department charged with conducting executions, and the owner of the chamber in architectural parlance—would clearly prefer to go about its business and has a long history of avoiding public oversight (unsuccessfully in this case), but continuing the death penalty is subject to judgment by a California electorate that is trending toward abolition. Part of the design’s banality (and its low-budget, medical undertones) may be intended to visually deescalate the death penalty debate in order to perpetuate the status quo. But perhaps even the CDCR embodies the same unresolved questions about execution that continue to reverberate in ballot referendums, courtrooms, and public debates. The bland nature of the execution chamber may also indicate a lack of investment in the procedure’s future, a realization that this is no permanent edifice but rather a set of rooms that may be demolished or at least renovated for some other purpose before long.

In court, the state argues that lethal injection is not a medical procedure requiring medically trained personnel—in part because the AMA directs its members not to participate in any part of capital punishment—even though, by attempting to remove the pain of death to further soothe an uncertain electorate, it moves ever closer to medical practice.14 And what of architecture? For now, the design of the death chamber is an acceptable part of architectural practice, but for how long will that remain the case? With an AIA ethics code that already requires members to “uphold human rights in all their professional endeavors,” and an active petition (of which I’m the director) calling for a clear determination that executions violate human rights, will this ambiguity remain?15 Can the architectural profession hide behind a mask of banality any more than the death chamber’s design shrouds its purpose? Time will tell.

-

This eventually became a book Berke coedited with Steven Harris, Architecture of the Everyday, (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1997). ↩

-

The project began in 2007 but, as discussed below, was not completed until 2010. The name of the architect, also discussed below, has not been made public. ↩

-

Readers wishing to learn more about this and similar projects can visit an exhibition on display October 14 to November 21, 2014, at the U.C.–Berkeley College of Environmental Design’s Wurster Gallery. "Architecture and Human Rights—Spaces at the Line" highlights spaces that house activities deemed to violate human rights: execution chambers, supermax prisons, and juvenile isolation cells. It is organized by Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility (www.adpsr.org), of which the author is currently president. ADPSR publishes additional information on the architecture of execution chambers and solitary confinement in relation to human rights at adpsr.org/home/ethics_reform. ↩

-

Morales v. Tilton, U.S. District Court in the Northern District of California, December 15, 2006. ↩

-

Incidentally, the refusal of doctors to participate in the administration of the death penalty is a precedent for ADPSR’s campaign calling on the AIA to implement a similar ethical ban of violations of human rights and public health, safety, and welfare. I use the phrase condemned man to recognize the vastly greater frequency of executions of men as compared to women: Only 2 percent of death-row prisoners are women, although in recent years up to 6 percent of death sentences have been handed down to women: deathpenaltyinfo.org/women-and-death-penalty. ↩

-

Ironically, this was around the same time that a separate panel of federal judges found the overall California prison system to be so overcrowded as to be unconstitutional in Brown v. Plata (see, for instance law.cornell.edu/supct/html/09-1233.ZS.html, accessed 9/15/2014); this, despite more prisons having been built in California in the previous three decades than anywhere else in the country or around the world (Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California, [Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007] 26). ↩

-

Mark Martin, “New Execution Chamber Infuriates Lawmakers/Facility at San Quentin was built quietly,” San Francisco Chronicle, April 14, 2007, sfgate.com/news/article/NEW-EXECUTION-CHAMBER-INFURIATES-LAWMAKERS-2565265.php. ↩

-

Seeing one such article in the San Francisco Chronicle was a powerful motivator of my own personal involvement with ADPSR’s petition asking AIA to prohibit the design of execution chambers. It led me to realize that the tools architects routinely use to make the world a better place—as I see my work and the profession’s broader purpose—can also be used to much more sinister effect. ↩

-

The final regulations for the Prison Rape Elimination Act require all spaces within prisons and jails to be directly ↩

-

The fourth subteam, record-keeping, has members distributed with the other three teams and with the warden and other leaders of the execution process. ↩

-

The division of labor seems intended to spread the responsibility for actually killing the condemned man across enough people so that no one “team member” has to appear to be an executioner, either to him-/herself or to the public. Public fondness for executioners is not great. This was true even when execution was a more common practice: Executioners were not allowed to live within the walls of medieval European cities. ↩

-

California’s regulations call for San Quentin prison to be placed on lockdown during an execution procedure to forestall disorder; a correspondent of mine in a Texas prison reported that chicken and cake are served as a special dinner throughout the Walls unit of Huntsville prison on days when its death chamber is used, marking a kind of bacchanalia of execution days. ↩

-

Amnesty International: “Death Penalty Facts,” updated May 2012, http://www.amnestyusa.org/pdfs/DeathPenaltyFactsMay2012.pdf accessed 9/15/2014. ↩

-

To further controversy: The makers of the drugs used in most U.S. lethal injections refuse to sell their products to state governments for use in executions and have threatened to stop selling in the United States entirely if their products are used for execution without their consent. Death penalty states have responded by using compounding pharmacies to make after-market versions of the same chemicals and have refused to divulge the identity of the pharmacies involved. ↩

-

See www.tinyurl.com/aiaethics for more information. ↩

Raphael Sperry is an architect and green building consultant, President of Architects / Designers / Planners for Social Responsibility, and Adjunct Professor at California College of the Arts where he teaches the course “Rights, Power, and Design.” He is writing a book on architecture and human rights.