When the Clippers are doing well…it feels like the world is in the right gear and everyone’s going to understand our record.

— Angus Andrew, the Liars1

Soccer makes you forget that the rich control politics. It makes you forget that the rich become richer. It makes you forget your own poverty and plight. It makes you settle for injustice and accept that the rich own the soccer clubs.2

— Bubbi Morthens, Icelandic folk rocker

“Place Iceland’s seven indoor halls in Coventry,” former Iceland soccer manager Guðjón Þórðarson recently hypothesized—Coventry being an English city with a population that roughly matches that of Iceland—“and just wait and see what happens over, say, 15 years.”3 Þórðarson’s pronouncement is reminiscent of Kevin Costner’s famous line “If you build it, he will come,” from the 1989 film Field of Dreams. In that scene, Costner wades through a cornfield and hears a voice whispering, telling him he should build a baseball diamond in the middle of it. The “he” has since been transformed into a “they” in popular culture, de-emphasizing the biblical connotations of the original phrase and giving it new life as an adage to be deployed in aspirational public works projects, often oriented around sports complexes.4

Variations on Guðjónsson’s “Field of Dreams promise” will be given frequently in the coming month of June 2018, as Iceland heads to its first World Cup tournament in Russia. With a population of only 330,000, it will be by far the least populous nation to qualify for the Cup. Regardless of how well Iceland plays in the tournament, simply appearing will be an extraordinary feat. It is not my intention here to speculate on the reasons why national teams perform well, and I am cautious about attributing sporting success to causal relationships.5 Any such performance will always be due to a combination of genetic, demographic, economic, environmental, and cultural factors, not to mention the vagaries of chance and whatever it is that creates that thing called “momentum” in sports. Many of those influences also comprise what could be referred to as a governmental apparatus, to loosely adopt Michel Foucault’s terms, and within this apparatus, I intend to focus on one factor—the environmental—and the role of Guðjónsson’s “indoor halls” in Iceland’s “managed miracle.”6 These halls, also known as “soccer houses,” are “environments” understood in the most literal sense, some complete with temperature and humidity controls. They comprise a series of “well-tempered environments”—to quote Reyner Banham—dotting the island’s coast, in which an unvarying 10°C reigns, a perpetual English spring in the deep of the Icelandic winter.

Indoor sports environments are hardly a new or novel phenomenon—and yet it would be hard to imagine works on such scale dedicated to such small populations elsewhere. Other Scandinavian countries come to mind in this regard, but the investment in soccer infrastructure for Icelandic rural villages remains an outlier even in that context.7 Glancing at an aerial view of one of the “houses” set in one of the smaller villages, one can see that the investment is not financially sustainable in any traditional economic sense—such extensive square footage could not come close to being remunerated through registration fees, ticket sales, and rentals to local users. In most cases, therefore, the houses are built by the municipalities and financed with taxpayer money. The space is then leased to municipal sporting organizations through what is effectively a subsidy, without money ever changing hands. The taxpayer’s wages, most of which derive from the three primary industries, tourism, fishing, and aluminum (in order of percentage of GDP), are thus syphoned into artificial turf, steel trusses, and hot air. What comes out on the other side of this indoor athletics apparatus is a World Cup–qualifying men’s soccer team. To fully understand the soccer miracle then requires a careful reading of soccer houses as participants in a complex economic system in which private and municipal money is deployed in myths of national economic resilience, and in which the urban-rural relation—and its corresponding pair, the service and the real economy—produce a particular social and built environment.

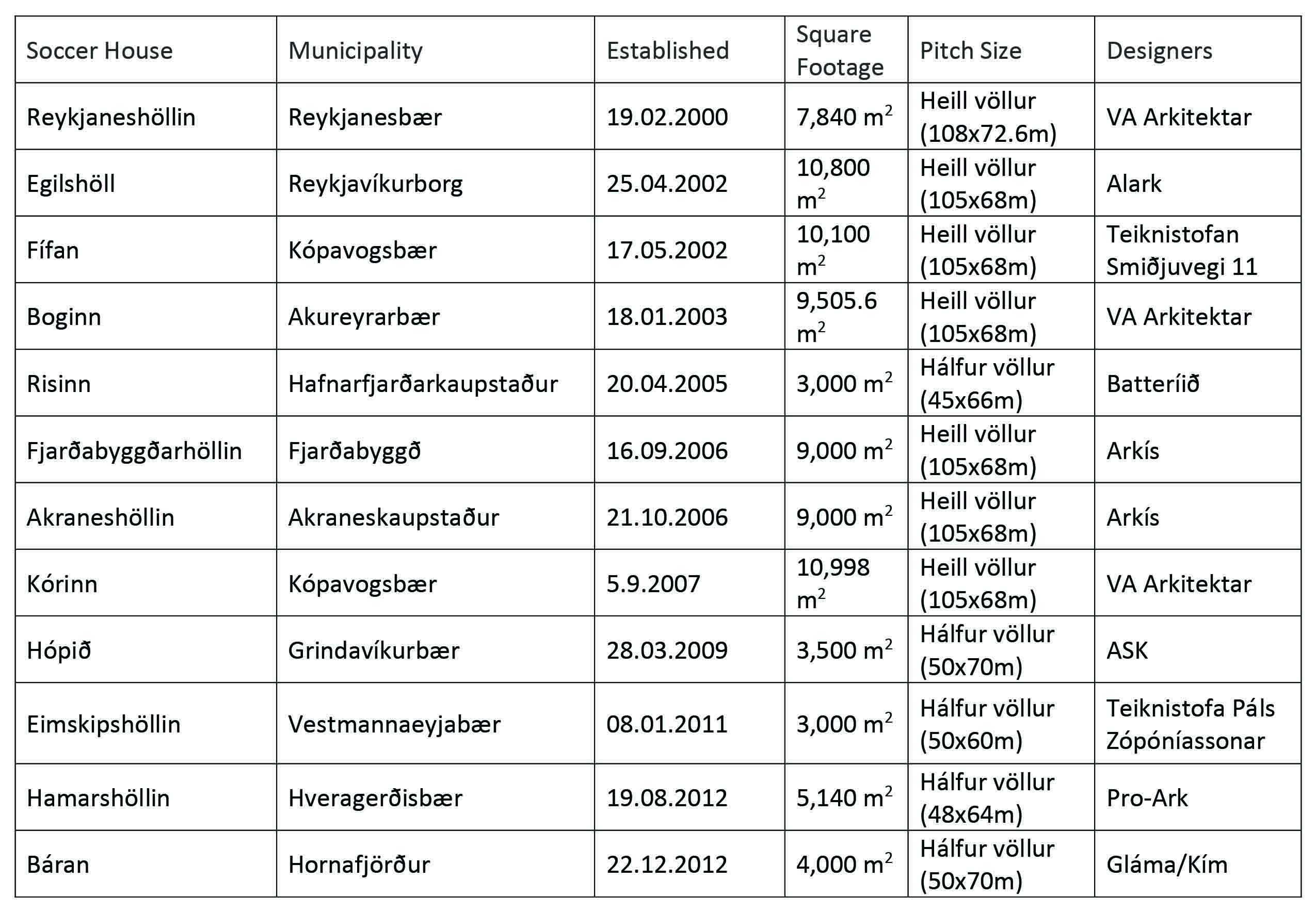

The Soccer Houses

A “soccer house” is, in short, a hermetically sealed superstructure built over a soccer pitch. The ensemble consists of a variety of sizes, structural systems, and materials. The island sports twelve such houses, built between 2000 and 2012, with many more in the planning stages. All are concrete slab-on-grade structures, topped by artificial turf. Ten of them are spanned by steel trusses. One of them, Báran (i.e., the Wave), to be discussed at length below, consists of a three-pinned-arch structure assembled from continuous locally manufactured glulam beams. Another exception features an inflated bubble structure, requiring over-pressure from the inside to keep the PVC cover aloft.

Some houses feature full-size competition pitches, but more commonly the pitches are half-size. The latter are not intended for competition, since the Icelandic soccer season takes place over the summer when the weather is fair. Rather, the houses serve a wide range of publics, from the club-level team down to very young children and groups of amateurs, who do not use full-size pitches, making the smaller sizes easier to fill and therefore more efficient economically.8 The consequence of these modest requirements is that the houses are designed primarily for practice—most facilities have no provisions for onlookers, and some even have no changing rooms and restrooms. This is an essential point; even though the larger of the houses, with their full-size pitches, are designed to fulfill the Icelandic Soccer Association’s (KSÍ) requirements so they can accommodate legal matches, they hardly ever do.

Urbanistically, the soccer houses are gigantic non-events in the village landscape. In some of the smaller villages, the only other buildings of a similar scale are fisheries or for heavy manufacturing, and in at least one case, a building system that had originally proved successful for industry was adapted for use to cover a pitch, the Finish Best-Hall system to be discussed in detail below. Even so, the houses are the most active social gathering sites in many villages, where opportunities for social activities can be slim—places where relationships and comradery are forged in changing rooms, on sidelines, and on the pitches.

The general appearance and material selection is one of economy, but even so, the soccer houses retain a utilitarian beauty, in their blank, gigantic monotony, dotting the coastline like so many beached whales. Some of them are bought fully engineered from abroad while others are given subtle treatments by architects. One such example is the Wave in Höfn, designed by Gláma/Kím architects, an Icelandic practice known for its restrained neo-modernism. The Wave is the only building of those erected to date that was fully donated by a local fishing company, Skinney Þinganes, to the municipal sporting organization, without municipal funding. This gave the architects leeway to produce a more rarified piece of architecture than some of the other soccer houses. The building is understated, with its visual concrete base, industrial-grade detailing, and use of exquisite locally fabricated, bent-pine glulam beams, forming an array of three-pinned arches. The interior furniture, as well as the custom-built windows, are executed in the same pine.

In a clever contextualist move, the building is clad with Aluzinc corrugated steel sheets, simultaneously conjuring up three national imaginaries on different scales. First, corrugated iron invokes the Icelandic timber-framed houses, the oldest continuously inhabited houses on the island, which define the appearance of village centers. These houses were initially clad in painted wood paneling, later replaced with corrugated iron. Immediately recognizable by their gabled roofs, they have since become the most romanticized Icelandic house typology, evoking a touchy-feely imagery of the “human scale” despite themselves. Second, corrugated iron recalls the industrial counterpart to the timber-framed houses: the shacks in which twentieth-century Icelandic homeowners worked, and from which they probably derived the economizing idea of using corrugated iron as a replacement for maintenance-hungry wood paneling in the first place. Third, “corrugated iron” in Icelandic literally translates as “wave iron,” creating an explicit relationship between these buildings and the sea they hold on to so tightly for their livelihood. The name of the Wave in Icelandic, “Báran,” therefore explicitly references the cladding material as well as the sea, completing the metaphor and tying together the three scales; village domesticity, national industry, and the ocean on which each feed. The contextualism does not stop at metaphor and materiality—The Wave is one of the few cases in which the architects thought about opening the building up to village life, through ground-level openings exposing the interior activities to the street, and expansive clerestory windows bathing the interior with light during the day.

Over the course of the European Cup tournament two years ago, when it had dawned on the world of soccer that Iceland had a respectable men’s squad, international news organizations began dispatching reporters to the island to investigate the sources of the Icelandic soccer “miracle.”

In Sports in Iceland, Halldórsson argues that the men’s team’s success cannot be attributed to the soccer halls, pointing to the deadpan empirical fact that few of the 2016 national team’s players ever played on them—they were either too old or had been playing in Europe for professional clubs before the Icelandic houses could affect their game.9 Although Halldórsson’s point is well taken, it does not invalidate my own focusing on the houses in this text: Icelandic professionals on the continent universally enjoy better year-round environmental conditions, both outside and in the indoor halls of Europe’s soccer clubs. This confirms that the more stable a player’s practicing environment, the more precisely he or she will be able to execute during a match. There is another argument that takes even more wind out of the KSÍ’s promotion of its Field of Dreams promise: The national women’s team, which had already reached the European Cup for two tournaments in a row in 2016, and would soon participate in the third, had none of the access to soccer houses that the men had when they first qualified in 2009. A quarter of those now existing had not even been built, while even those that had were only a couple of years old. This disregard for women’s sports is, of course, nothing new, and it is exacerbated through the monoculturalism of big sporting events, where one frequently hears, “Well, the men are more popular,” which may be the case but which also makes this the case.

As Halldórsson shows, the foreign journalists were quick to toe the KSÍ line. Without fail, these articles mention the soccer houses as the main source of Icelandic soccer’s success along with improved professionalism of Icelandic coaches.10 Here, the soccer houses are part of an energetic strategy established by the Icelandic Soccer Association. The KSÍ had organized trips to Norway in the nineties to observe Norwegian successes with indoor soccer houses and attempted to get the municipalities to buy into erecting houses in Iceland following their standards. Although this happened—by 2000, the first hall had risen in Reykjanesbaer (KSÍ did not possess the power or money to make it happen)—the incentives always had to come from the municipalities and the soccer teams themselves.

A common trope of media coverage, as already mentioned, is the reference to the financial crisis of 2008, parroting what has often been said about the Icelandic way out of it—deposing its government, jailing its bankers, rejecting austerity, and keeping the welfare state intact—and offering soccer as an exemplar beneficiary on the municipal level.11 The implication is that other, more populous nations with less egalitarian soccer systems would do well to follow heroic little Iceland, which continued to put money into soccer despite economic hardships.

These accounts never mention that Iceland’s more tangible economies, fishing and smelting, were never in danger, and, indeed, did well after the crisis precisely because of the fall of the króna, helping to stabilize the economy. The economy could therefore be rebuilt minimally reformed, let alone restructured. In a stunning manifestation of complacency and forgetfulness on behalf of the Icelanders, when Iceland played at the European Championship in France in 2016, its government was a coalition formed out of the same parties that had overseen both the privatization of the Icelandic banks in the first years of the millennium and the entrenchment of the ITQ system in the eighties and nineties, more on which below.12

Soccer, and particularly the soccer houses, play a role in production of this complacency, for better or for worse. This production is best discussed in terms of the politics of the rural and the urban. In Iceland this relation has, like everywhere else, been held in a precarious balance. The countryside has produced most of the Iceland’s wealth—the industries of tourism, fishing, and the harvesting of electricity for energy-hungry manufacturing do not belong to the city, in the case of Iceland, even as metropolitan centers come to dominate economies elsewhere. Despite having recently been overtaken by tourism as the most lucrative industry, the fishing industry is still the dominant, and most entrenched, productive sector in the country.

Icelandic fisheries have, since 1983, operated through an individual transferable quota (ITQ) system of resource management, which has proved exceptionally efficient ecologically. Through the system, vessels are allowed to catch a finite tonnage only within the two-hundred-mile waters of the island, creating a finitely managed resource. This allows for scientific planning of the sizes of fish stocks, with the national Marine Research Institute adjusting quota numbers to the state of the fisheries. This has, in turn, allowed most fish stocks that were depleted in the 1980s, when the system was initiated on a trial basis, to rebound. The ITQ is effectively an “enclosure of the sea” designed to avoid an oceanic “tragedy of the commons” (to modify a pair of formulations coined in an industrializing nineteenth-century England). 13 The idea is that through handing a mismanaged, finite resource to a select group of ship owners that already have the know-how to fully exploit the resources, they will be more effectively managed, since owners will, according to liberal economics, naturally try to maximize the profit of their investment.

If this privatization of the fisheries has been successful from an ecological point of view—and it has certainly been an economic success for the lucky owners of the quota—the social effects of this privatization have not been as positive. Because shares of that quota are fully transferable, it has consolidated into fewer and fewer hands, to the extent that it can, in certain instances, leave whole villages completely bereft of fish. For villages that exist almost entirely because of the fisheries, this affects every single inhabitant. Moreover, most of the capital generated by these industries is extracted from the communities that produce it, instead ending in the bank accounts of a few “quota kings.” The municipalities are not on the winning side of this equation, and neither are the sports organizations.

In the last decades, the fishing villages have increasingly found it difficult to retain young people, who choose higher education and comfortable service sector jobs in the city over well-paid manufacturing jobs in the countryside. This is compounded by the villages’ own difficulties retaining fishing vessels with quota and the accompanying employment. Their only hope is to hold on to their tax bases and retain, or at least encourage the return of, young people and, failing this, attracting immigrants. Moreover, because of the peculiarities of the Icelandic electoral system in which rural votes are worth three times that of urban ones, it has long been in the interest of the center and right parties to keep the people in the countryside content where they are. The “quota kings,” many of whom reside in Reykjavík, are represented by those same parties in parliament and are therefore held together in a curious electoral alliance with their workers in the country. Fish and soccer comprise the net that holds this alliance together.

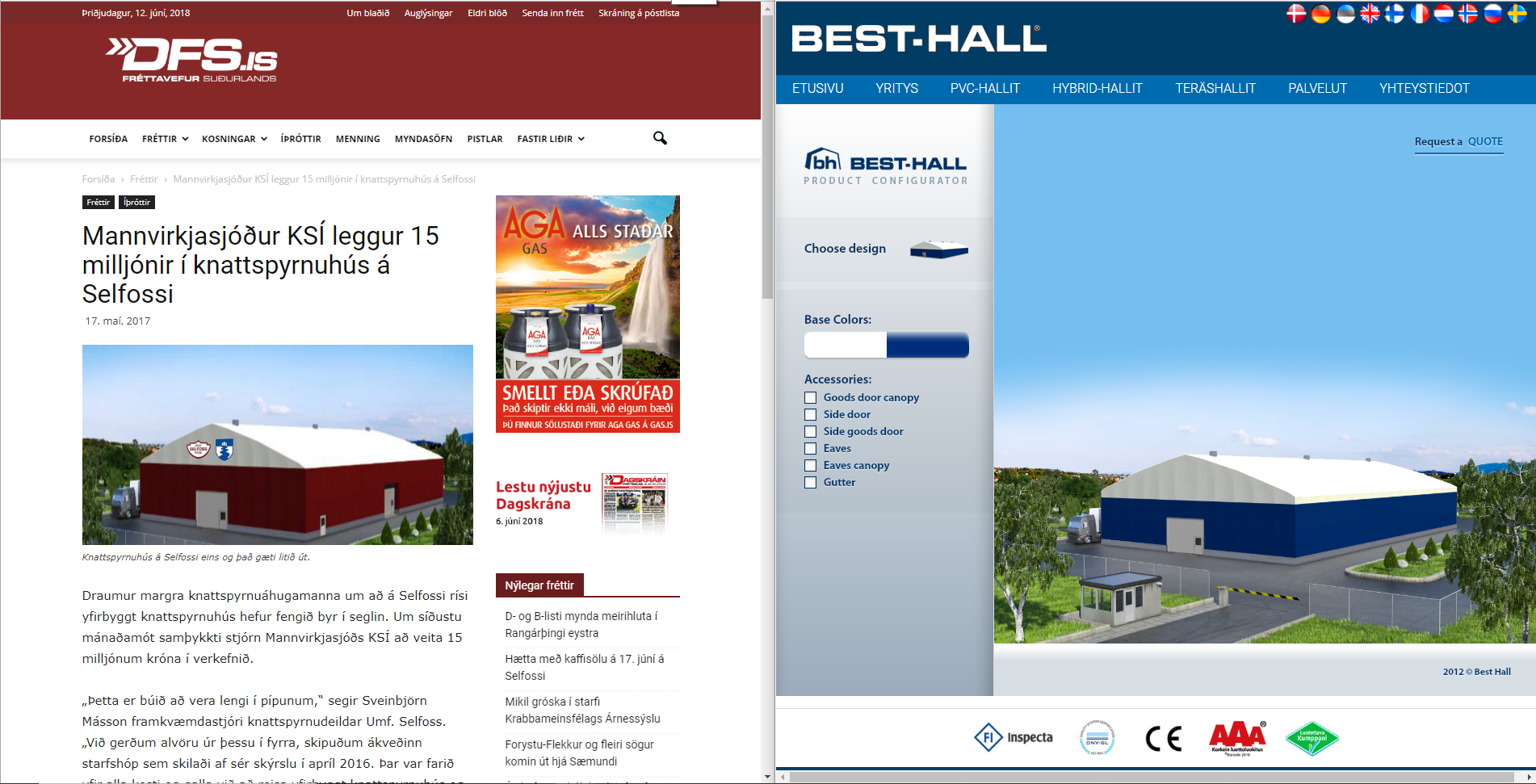

Perhaps another case study will put this net in relief. Of the soccer houses that have caught the eye of foreign reporters, perhaps the most distinctive are the structures erected by the soccer division of FH, a neighboring town of the capital Reykjavik. These steel-and-PVC structures are imported wholesale from the Finnish company Best-Hall, “the leader in product development and quality for buildings with steel lattice structures,” specializing in “warehouse, industry and sports buildings.”14 The PVC cover is translucent during daytime, providing a calm, diffuse light. The owner of the exclusive import rights to these structures, the ebullient Jón Rúnar Halldórsson, who generously engaged with me during the writing of this article, is the former owner of salt import company Saltkaup, which he sold in 2007. In his capacity as owner of the company, he built several salt warehouses around the country utilizing Best-Hall designs, and as the director of FH soccer club, he oversaw the building of two Best-Hall structures for FH, with one more in the planning stages. FH is the only soccer club that finances its own soccer houses, supposedly avoiding the obvious conflicts of interest that would arise if the municipality were funding it.15 The case of the relationship between Saltkaup, the Best-Hall structures, and a soccer company shows the relationship between capital, the real economy (salt is both a major ingredient in fish processing and storage while being a key lubricant in keeping the wheels of the Icelandic economy turning—no salt, no roads) and soccer on a small island.

Sports are a quintessentially biopolitical practice. First, they develop the physical capacities of those that play them. They create healthy, capable bodies that are supposed to house healthy, capable souls that are, again, attentive to their bodies and take care of them like clockwork, fitting their daily fitness regimen in with their work like good, productive citizens. They serve a major role in combating obesity, alcoholism, and drug addiction, all major health problems that take their toll on economies with strong welfare programs such as Iceland. They take up time that otherwise might be spent on less empirically productive activities. Finally, sports are entirely quantifiable—that is, after all, the entire point of modern sports—that physical activity can be measured, quantified, compared, developed, charted, predicted, bet on.16 In the case of Iceland, civil society’s intensive investment in soccer, and the national narrative around it, only heightens its biopolitical effects.

For Foucault, who developed the concept of biopolitics, the term referred to the process through which the state develops the body of its citizens to maximize their productivity while simultaneously maintaining their psychological malleability. However, in the case of the phenomenon of sporting, what we see is not a top-down application of biopower to the body of the citizens by the state but rather a proliferation of biopolitical strategies that pass from institutions to persons to corporations, across national borders. An Icelandic teenager who unwittingly picks up a copy of a fitness magazine at the village gas station and makes a subtle adjustment to her lifestyle choices as a result participates in biopolitics. Power is applied, nudging her behavior in some direction, however predetermined. It is difficult to ascertain to which end. To get her to buy more magazines, maybe? As I reach my conclusion, I do not claim to have good answers. But I hope to have at least disarmed some bad ones.

Team sports therefore produce a certain type of individual, and even certain types of nuclear families through rituals of sports playing and sports patronage. These hypothetical families might have their children involved in sporting activities and attend bigger sporting events. Sports bolster village morale and create an identity for villagers to gather around. Bigger events provide a level of novelty and excitement. This way, sports facilities become cultural centers, far more conductive to intermixing of classes, political orientations, and different ages of people than other cultural events, which retain a certain elitist character, even in a rural village. The ultimate validation of this biopolitical production, on the scale of the whole country, this complex intersection between politics and leisure is the unlikely event of an actually existing world-class men’s soccer team.

It is hard to be sitting in one’s chair writing this and not feel a little bit paranoid in the face of these facts. It’s a beautiful Saturday in New York, less than a week before Iceland’s first game, against Argentina. My article to the Avery Review editors is overdue. My son is waiting for me to press send, so we can go out to play soccer in Riverside Park. I just got myself a pair of Adidas Sambas—I, who have hardly touched a soccer ball in my entire life. We are, after all, Icelandic, and taking us as an example, the existence of this team validates the whole enterprise of this governmental apparatus and the working-class Icelandic voters it appeals to. And at the same time, perversely, Iceland’s “soccer miracle” can make it seem so simple hiding the multiplicity of parts that supports its sporting infrastructure and its financing. Stories of a winning team inject a form of naturalism into a complex orchestration of administrative sporting organization, fishing monies, voter morale, and economic narratives: Place Iceland’s seven indoor halls in Coventry. Build it, and they will come. And while you are enjoying it all, who cares about somebody else’s money, class politics, the urban and the rural, fishing, and the rest? Enjoy!

List of Icelandic Soccer Houses and their designers:17

-

Ian Cohen and Angus Andrew, “Liars,” interview, Pitchfork, March 31, 2012, link. ↩

-

Bubbi Morthens, tweet on June 5, 2018, link.

“Fótbolti fær þig til að gleyma þeir rìku stjórna pólitík þeir ríku verða ríkari fær þig til að gleyma eigin fátækt og basli fær þig til að sættast við óréttlætið og að þeir ríku eiga fótboltaliðin.” ↩ -

AP, “Soccer Success: Iceland Investment Takes Tiny Nation to WCup,” USA Today, December 2, 2017, link. ↩

-

The first reference I can find in the press using the line in this connection is a 1993 Los Angeles Times article: Mike Clary, “They Built a Field of Dreams, but No One Came: A City’s $138-Million Baseball Showcase Fails to Lure a Big-League Team,” Los Angeles Times, March 8, 1993, link. This article comes complete with a Field of Dreams reference of its own, in which the misremembered “they” has already won out: “After city officials had been jilted several times, Dodge says, former baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn wooed them with what would become known as the ‘Field of Dreams’ promise: ‘If you build it, they will come.’” This article may have been a first in a cottage industry of reports, books, and articles that play with the phrase or the movie, culminating in a hearing before the US Congress’s Subcommittee on Domestic Policy of the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform titled Build It and They Will Come: Do Taxpayer-Financed Sports Stadiums, Convention Centers, and Hotels Deliver as Promised for America’s Cities? from 2007. See also Field of Schemes: How the Great Stadium Swindle Turns Public Money into Private Profit by Neil deMause and Joanna Cagan. ↩

-

In this, I partially agree with sociologist Viðar Halldórsson at the University of Iceland. In a recent book, Halldórsson dismisses the “Fields of Dreams’ Promise,” along with what he sees as journalist’s coaching obsession, emphasizing the role of culture in the formation of a successful national team. I agree with his skepticism of simple causal explanations but still remain unconvinced of the culturalist argument he supplements them with. Then again, I am an architectural historian and he is a sociologist, so perhaps it is not surprising that the fault line corresponds so neatly with our disciplinary gates! See Viðar Halldórsson, Sport in Iceland: How Small Nations Achieve International Success (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2017). ↩

-

Barney Ronay, “Football, Fire and Ice: The Inside Story of Iceland’s Remarkable Rise,” the Guardian, June 8, 2016, sec. Football, link. By “governmental apparatus,” I do not mean government in the literal sense, in the form of a top-down governmental policy. Rather, I mean it in a diffuse sense, where a cultural artifact such as a soccer house is inscribed in networks of power, weaving together culture and politics, people, and, as I will argue for further below, fish. What is precisely so intriguing about the soccer houses is their ambiguity. From where is the power being applied, and to what end? ↩

-

See Kolbjørn Rafoss and Jens Troelsen on the relationship between the Nordic “Sport for All” model: “Sports Facilities for All? The Financing, Distribution and Use of Sports Facilities in Scandinavian Countries,” Sport in Society, vol. 13, no. 4 (May 1, 2010): 643–56, link. ↩

-

Some houses are even used by non-soccer players, such as golfers, joggers, and public-school gym classes. ↩

-

See Halldórsson, Sport in Iceland, 44. For Halldórsson’s primary source on this observation, see Óskar Hrafn Þorvaldsson, “Gerðu hallirnar Frakklandshetjurnar virkilega svona góðar?” (Were It Really the Soccer Houses that Made the French Heroes So Good?), Fréttatíminn, July 12, 2016, link. ↩

-

See, in addition to the others cited, Jonathan Liew, “Euro 2016: The Story of Iceland’s Unlikely Footballing Revolution,” the Telegraph, June 3, 2016, link; Davis Harper, “Volcano! The Incredible Rise of Iceland’s National Football Team,” the Guardian, January 30, 2016, link; and “Iceland: How a Country with 329,000 People Reached Euro 2016,” BBC Sport, November 15, 2015, link. ↩

-

Joshua Kloke, “How Did a Nation of 330,000 People Qualify for Euro 2016? The Secret behind the Iceland Miracle,” Goal Euro 2016, June 27, 2016, link. ↩

-

For a comprehensive view from the Icelandic Left of the history of the collapse of the Icelandic financial system, and its tragically wholesale reinstatement, see Viðar Þorsteinsson, “Iceland’s Revolution,” Jacobin (March 2016), link. ↩

-

For insight into the ITQ system and its relationship to political geography, I rely on Mattias Kokorsch and Karl Benediktsson, “Prosper or Perish? The Development of Icelandic Fishing Villages after the Privatization of Fishing Rights,” Maritime Studies (May 2018): 1–15, link. ↩

-

Sveinn Arnarsson Skrifar, “Umboðsaðili Fær Ekki Greidda Krónu,” Vísir, March 31, 2015, link. ↩

-

See Niko Besnier, The Anthropology of Sport: Bodies, Borders, Biopolitics (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018). ↩

I would like to thank Jóhannes Þórðarson (Gláma/Kím), Jón Rúnar Halldórsson (FH), Gísli Gíslason (KSÍ), Þóroddur Helgason (Fjarðarbyggðarhöllin), Sigurður Guðjónsson, (Límtré Vírnet), Viðar Halldórsson, and everyone else I spoke with in the preparations for this article. Thanks to Arnór Sigfússon for the drone photography. Thanks to Dennis Pohl for the stimulating discussions. Finally, thanks to the Avery Review editors for their generous feedback and for tolerating my frantic back and forth.

Óskar Örn Arnórsson recently completed his third year of the PhD in Architectural History and Theory at Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation (GSAPP). He is also pursuing comparative and cross-disciplinary work at the Certificate in Comparative Literature and Society at the same university. His dissertation is about the architecture of international governance, from the Treaty of Vienna in 1815 to the Present. In his Masters thesis at the program for Critical, Curatorial and Conceptual Practices, also at the GSAPP, he compared the renovation of the United Nations Headquarters in New York, completed in 2015 to the initial buildings, planned and built Mid-Century. Prior to his academic work, Oskar, originally from Reykjavík, Iceland, pursued architecture at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts School of Architecture in Copenhagen and the Cooper Union in New York, before embarking on an architectural career that lasted five years, most prominently with the studio of Diller, Scofidio + Renfro in New York and PK Arkitektar in Iceland.

He never played soccer, but was a decent basketball player, appearing for three minutes of one game in the Men's Premier League during the 1999-2000 season.