It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead. 1

—James Joyce, “The Dead,” from Dubliners

On the afternoon of January 12, 2020, Taal Volcano in the Philippine province of Batangas erupted after forty-seven years of dormancy. Ash propelled into the air and quickly covered the surrounding area, even reaching Metro Manila, about 60 miles to the north. Catastrophe struck the villages around the volcano’s crater lake. Many of the villages housed people whose fisheries within the lake were their livelihood. Global news media images of farm animals, homes, and roads buried in ash tell tales of structural ruin and human displacement, with nearly forty thousand people from the Batangas and Cavite provinces retreating to cramped evacuation centers set up by government authorities. Nearby, atop a mountain ridge next to the lake, a resort and condominium development named Tagaytay Highlands was also blanketed with ash, though evacuees were better off. The vacationers in the Highlands rushed to join other family members or return to their city homes in Metro Manila amid the ashen chaos. Many condominium owners of the Highlands were, luckily for them, not present.

For those stuck in the crisis zone, lack of medical supplies pushed a Department of the Interior and Local Government official to release a statement asking the public to “donate clean drinking water, food, emergency medicines and other basic essentials,” despite the Duterte government cutting the Philippine emergency fund to 16 billion pesos (a little over 300 million USD).23 In comparison, almost twelve times that amount (P 185 billion) has been directed to the Philippine police forces, and over twenty times the amount (P 365 billion) will be dedicated to developing the Metro Manila subway system, financed by the Japan International Cooperation Agency and executed by a group of Japanese design and construction corporations.45

The stark differences between the experiences of highly mobile vacationers and condo owners in Tagaytay and the peasant, small vendor, and wage-worker population of the Taal lakeshore (alongside the uneven distribution of funds between public service, national military, and urban-centric development) tell of deep, systemic colonialities that have defined Philippine economy, culture, and spatial forms. With this deeper interpretive framework, Tagaytay and other mountaintop leisure infrastructures represent a geographical phenomenon that spans indigenous, colonial, and postcolonial design in the archipelago and become key contested sites of a longue durée history of capital accumulation, foreign profit, and oppression of the peasantry in the Philippines.

Tagaytay

The city of Tagaytay has been and remains vastly different from the smaller municipalities around Taal Lake. A summer retreat for those financially able to escape Metro Manila’s heat, smog, traffic, and other unsavory aspects of the capital region’s urban sprawl, Tagaytay’s primary job market is in the hospitality industry, supporting a growing number of hotels, resorts, and condominium developments built in the cooler, less severe climate of the mountains. Tagaytay Highlands, parts of which are currently under construction, is one of the more exclusive developments, boasting its ability “to develop investment-worthy properties for those looking for high-quality amenities, holistic environs, security and privacy, and accessibility.” The project’s website asks, “just what is it about Tagaytay Highlands that makes your weekends special?” and provides its own answer: “more than the exclusivity, more than the luxury, more than the finer things in life, it’s the great destination you can call your own.”6

The development is a condo hotel, a popular tool for drawing foreign investment that abides by the Condominium Act of the Philippines, passed in 1966 under the famously corrupt Philippine president Ferdinand Marcos.7 Under this law, corporations can sell as many condominium units to foreign individuals as they choose. It acts as a loophole that allows foreign property ownership in the Philippines—otherwise barred—while also working around percentage restrictions on foreign corporate stakeholders. Condominium hotels such as Tagaytay Highlands are essentially a contemporary form of colonial investment opportunity for the wealthy international community of Southeast Asia, a modern protocol for developing land in continued service to its landlord-driven, semi-feudal, and semi-colonial economy.

Tagaytay Highlands was originally conceptualized by a young professional from Belle Corporation and later acquired by SM Prime (formerly known as Shoemart), one of the largest land-owning companies in Southeast Asia founded by the late Chinese Filipino businessman Henry Sy, Sr. As of 2018, SM Prime had built seventy-two malls, sixty-three high-end residential projects, eleven office buildings, and a number of new ventures in hotel, convention center, and trade hall developments in the Philippines, totaling over 600 billion PHP in assets.8 As with many large land-holding ventures in the Philippines, this kind of wealth is primarily a family affair, with three younger Sys on the Board of Directors. Amado Guerrero describes this social class in detail in Philippine Society and Revolution: “The comprador big bourgeoisie links the international bourgeoisie with the feudal forces in the countryside and has profited most from trade relations with the United States and other imperialist countries… It has accumulated the biggest capital locally in its role as the principal trading and financial agent of US imperialism.”9 Written in 1970 and published by the Communist Party of the Philippines, the systems and structures outlined in the book’s comprehensive class analysis have only deepened and diversified, becoming more deeply entrenched in semi-feudal Southeast Asian reproductions of capitalism (the West’s most persistent and pervasive form of empire).

On my own recent family tour of the Philippines, I witnessed firsthand all the Western-influenced amenities of the Highlands. As a first-generation Filipino American who had only visited the homeland a handful of times, I was struck by the pure essence of the country club, itself a familiar indicator of wealth that my immediate family is close to but does not quite have. We were invited to stay by a tita whose own successes in the Philippines afforded us accommodation there for a night, and we slept in The Lodge, a log cabin-style spa and hotel building replete with moose antler chandeliers and fireplaces in common areas. I could imagine gruff white men with rifles coming back from a hunting trip or down-jacketed skiers drinking hot cocoa. But the lobby was empty, save for my two titas waiting to greet us over a hearty dinner of chicken and mashed potatoes.

The next day, my father, an immigrant to the US who achieved his own version of the American dream investing in California real estate, started a conversation, naturally, with a real estate agent. The young man quickly called a driver to give us a tour. Along this tour, the Highlands’ history and intent became increasingly and unbearably apparent. The fascinating, appropriative architectural forms act as visual manifestations of the Tagaytay Highlands marketing copy, with the development’s log cabin condominiums and The Lodge hotel where we stayed directly inspired by mountain resorts in Aspen, Colorado, despite there never having been snow in Tagaytay (or in the Philippines, for that matter) in recorded history.

Our guide took us to a model condominium filled with art books, shag rugs, and glass coffee tables, then on a short drive to one of the development’s newest marketing tools: the Horizon condominiums. The as-yet-unfinished complex consists of low-rise condominium buildings named after American golf courses—Augusta, Bay Hill, Gleneagle, Greenbrier, Pebble Beach, and Pinehurst—set around a central common area furnished with walking paths and a pool for those staying there. Of course, Tagaytay Highlands is home to two golf courses, respectively called the Highlands and the Midlands; in the condominium complex, prospective buyers are marketed a golf-ridden pleasure palace.

When we arrived, the Horizon construction site was eerily quiet, as empty as The Lodge the night before. We learned from our guide that the workers themselves—maids and janitorial staff, restaurant waitstaff, the chefs, the security guards, the caddies—are not permitted to enjoy any of the amenities to which they attend, or to be present in the development outside of working hours. The only exception to this is near the construction sites, where food vendors occupy temporary shacks, erected by the vendors themselves, that provide food and drink for the construction workers. Of course, our guide assured us, the shacks and workers would be safely outside of the development after construction is completed. It won’t be difficult to enforce; the entirety of Tagaytay Highlands is a gated community, guarded by walls and fences.

Dwelling on the Americanized signifiers of wealth in the Highlands, I could not shake the development’s strange haunting by Western style. Iyko Day provides a useful outline for this cultural phenomenon in Alien Capital: Asian Racialization and the Logic of Settler Colonial Capitalism, observing how “cultural production… magnifies settler colonial mythologies to reveal a system of representation that reproduces the logic of capitalism.”10 In transporting visual cultural production in North America to the mountains of the Philippines, the resulting mythology itself becomes a representation of a representation, a Baudrillardian simulacra eluding reality in favor of the brand of American wealth. These forms are nothing more than a rearticulation of capitalism “as a system of representation that is objective but immaterial, immanent but subject to resignification.”11

Inspired in form and function by American capitalist culture, the settlement is constructed for the express purpose of attracting wealthy Chinese, Japanese, and Filipinos; in other words, the small but significant social stratum defined by globalized Southeast Asian wealth. For many in the Philippines, this is the definition of success, and a life to strive for. Although American- and other foreign-owned enterprises in the Philippines have been restricted since the archipelago was granted independence, the Philippines’ colonial past has, in a manner similar to D. I. Saranillio’s analysis of Hawaiian colonial history, left “Native lands and resources… under political, ecological, and spiritual contestation,” while “the political agency of immigrant communities can bolster a colonial system initiated by White settlers.” Elaborating on this phenomenon, Saranillio poignantly considers how “the avenues laid out for success and empowerment are paved over Native lands and sovereignty.”12 In contrast, wage-earning Filipinos are literally hidden in their service to this wealth, with the semi-feudal nature of the Philippines readily apparent in the development’s inner workings. Tagaytay Highlands, then, is only the latest development in a broader capitalist and settler colonial system, the same system that planned and architected “hill stations,” mountaintop urban forms pioneered by white settlers of South and Southeast Asia with the explicit purpose of offering cooler oases to serve foreigners in a tropical land.

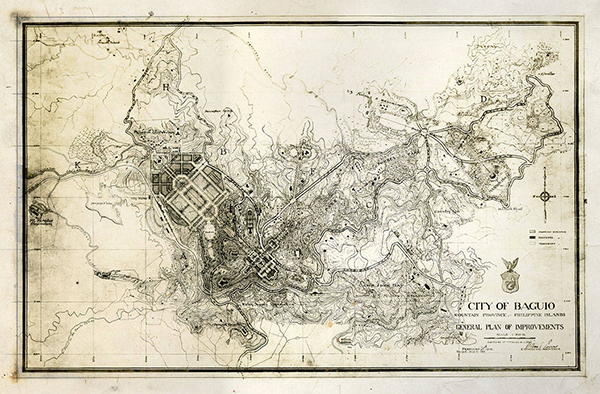

Baguio

Baguio was established by the US government among the mountains of Northern Luzon in 1900, deeming it the summer capital of its newly claimed colony after the Spanish-American War.13 The city was praised by Governor-General William Taft himself as having “air as bracing as Adirondacks or Murray Bay… temperature this hottest month in the Philippines on my cottage porch at three in the afternoon sixty-eight.”14 As the city’s access was limited to horse trails along mountain roads, the Americans hired Filipino and Chinese workers to build Kennon Road in 1903, with an American military encampment and “The Mansion”—the city’s so-called summer palace and then-residence of the governor-general—to follow. The Mansion was designed by architect William Parsons, while the city was planned by a pioneer of the American “City Beautiful” movement, Daniel Burnham (who was, incidentally, more of a businessman than a planner). Baguio thus has direct spatial referents in Chicago, Detroit, and Washington, DC, adorned by the Classical Revival architecture then popular in the US. In its monumental buildings, parks, and residences, there is a distinct lack of indigenous infrastructure, a subtle invisibility that is telling of the long-term, ongoing erasure of Filipino agency in its architectural and revolutionary histories.

Once a hunting ground for the sedentary indigenous Ibaloi Igorot people (literally translating to “mountaineers who live in houses”), the area was never fully under Spanish colonial rule due to the mountains’ natural defenses and Igorot tactics. The Spanish did, however, divide the region into rancherías, a term used across the Spanish colonial world to refer to small, rural, native settlements. These settlements were activated in 1899 during the Philippine Revolution, when the province was reclaimed as part of the revolutionary-led First Republic of the Philippines, with Baguio under the leadership of Ibaloi chieftain Mateo Cariño. As a truly independent, indigenous-led city, Baguio was short-lived; the US had by then already purchased the Philippines from Spain under the Treaty of Paris, and American forces proudly picked up the colonial torch in the centuries-long foreign occupation and control of the archipelago.

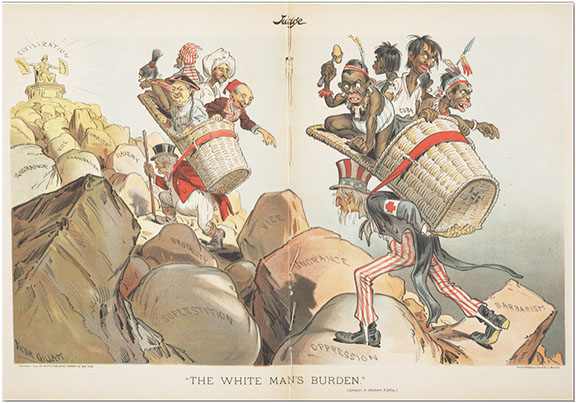

The Americans’ subsequent replacement of the Igorot infrastructure and community has deep, disturbing, and ultimately unsurprising cultural roots in the American conception of the “white man’s burden.” Derived from Rudyard Kipling’s eponymous poem about the United States’ “burden” after claiming the archipelago as a colony, the propagandistic, pro-imperialist poem was widely distributed to convince Americans, divided on the issue of the Philippines, of the moral obligation to civilize and raise up the “new-caught, sullen peoples / Half devil and half child.”15 While the archipelago’s rich material and visual cultures of art and architecture, writing, and structural feats (see the Ifugao traditional houses, replaced in Baguio; the Ifugao-made Banaue Rice Terraces; or even the more common yet particularly efficient bahay kubo) tell a different story—that of a complex, sustainable, independent ecology of unique societies—the design of the city of Baguio was an enthusiastic display of a warped moral duty that Americans felt toward the Philippines, which design historian David Brody considers as being “continuously secured and reinvented through the construction and planning of an artificial scape of architectural design.”16 What’s more, Baguio ultimately became an American pleasure palace expanded upon by William Cameron Forbes of the elite Forbes family, and governor-general of the Philippines from 1909 to 1913. In those four years, Forbes would build upon the archipelago’s summer capital to include a country club, golf course, and other amenities that, as Rebecca Tinio McKenna points out, together recreated “the society that such an establishment fostered.” Indeed, Forbes would utilize these amenities to reinforce Americanized ideals of high society even among Filipinos, inviting the likes of revolutionary leader Emilio Aguinaldo, future president Manuel Quezon, and others to mingle within the engineering feat of hilltop leisure infrastructure, slowly but surely encouraging wealthy Filipinos and Americans alike to invest in Baguio property. As such, the mountain city became not only a place of governance during the hotter months but also a structural manifestation of “what US tutelage offered” and “a stage for setting in motion new relations of social credit and debt.”17 It had become an “American imperial pastoral” masterpiece, an example of the luxury that wealth accumulation might afford to those willing to expand Filipino markets for raw materials.

Baguio’s history can, then, be directly referenced to understand Tagaytay, a city often deemed the “second” or “alternative” summer capital of the Philippines. The Highlands, along with Baguio and other contemporary hill stations, mirror in some respects what Frantz Fanon details, in African colonial states, about the structural elements of settler towns compared to smaller native villages:

The settlers’ town is a strongly built town, all made of stone and steel. It is a brightly lit town; the streets are covered with asphalt, and the garbage cans swallow all the leavings, unseen, unknown and hardly thought about… The settler’s town is a well-fed town, an easygoing town; its belly is always full of good things. The settlers’ town is a town of white people, of foreigners.18

This description applies to both Baguio and Tagaytay, elucidating the cold and difficult fact that both cities, in their infrastructures and architectures “made of stone and steel,” are explicitly in service to foreign control and investment. Indeed, Diana Martinez’s in-depth material analysis of reinforced concrete in the American imperial Philippines provides a critical framework for understanding how concrete, in its well-suitedness to fast, efficient building and as a manifestation of American “progress,” helped lay the groundwork on which to build an unprecedentedly durable economic empire.19 These colonial settlement architectures have functioned to uphold and reproduce the colonial system even decades after Philippine independence. Under the auspices of the culture of the vacation getaway, the Highlands continues the foreign wealth-infused structural tradition of the hill station. As a walled development, it acts as a clear contemporary manifestation of the semi-feudal (resort workers living outside of resort walls contribute to the SM Prime’s success in exchange for a much, much smaller sum) and semi-colonial (the resort itself, under condominium law, serves the agendas of foreign investors) state of architecture in the Philippines, forms that have effectively replaced all traces of Indigenous design in order to reproduce the systemic imperatives of a postcolonial society.

This phenomenon’s roots can be seen in the visual presence of the Philippines in the US during the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, when the United States imported around 1,200 “little brown brothers” from the newly acquired Philippines to construct temporary villages, sparking a sense of colonialist wonder in the American public and staging “the imperative of modifying the Philippine landscape with Western architecture.”20 Christopher Chanco describes the subsequent evolution in the reproduction of settler spaces in the Southern Philippines, noting the reproduction of particular spaces, “from the refugee camp to the agricultural colony… crucially, this need not involve a white-settler subject backed by a colonial state, but could occur even in the context of relations involving actors who are technically indigenous.”21 This spatial reproduction is to be expected, particularly when measures of Indigenous success are defined by the Western capitalist drive of land and wealth accumulation, and many efforts otherwise are quelled by militant government force.

People’s Park

Yet a different mountaintop near Taal Volcano, a short drive away from the Highlands, holds perhaps one of the most spatially and revolutionarily interesting would-be settlements of bureaucratic wealth in the Philippines. The People’s Park in the Sky (formerly known as the Palace in the Sky) is a Marcos-era mansion development project once riddled with corruption and opulence. Initiated by Imelda Marcos, construction of the mansion began in 1981 and was rushed to near-completion in 1983, when the opportunity to house President Ronald Reagan during his visit to the Philippines arose. However, when Reagan’s visit was canceled, the Marcoses simply halted construction. The development was left alone until after the People Power Revolution of 1986, when “the guards vanished and curious Filipinos began appearing to gaze, for the first time, at the unfinished palace in the sky.”22

After our tour of the Highlands—and upon seeing the half-finished structure from afar—my mother explained the history of the People’s Park, and I convinced my father to come along. My parents themselves had been privileged enough to flee the Philippines for the US just before the revolution and had never seen the park themselves. We walked up the steep mountain road leading from a makeshift, seemingly collectively owned visitors’ center (complete with sari-sari stores and a small restaurant); we made our way past small, Chinese-style guardian lion sculptures along the road up to the mountaintop. The park itself defies notions of a “park,” at least as defined by Baguio’s City Beautiful–inflected master plans. Instead, it is defined by its history as an architectural artifact of government greed and power, as well as of the people-led revolution of the last century. Incomplete, abandoned, and what in any other instance might be called ruins, the park/palace is now filled with Filipinos coming from nearby cities in a casual joy that any day spent at a park might have. It was a perfect day in the mountains, of course; we took in the majesty of the sunny view atop the mountain alongside other families, young couples on dates, and local tourists. Small vendor huts sold espasol and other small food items, temporary tattoos, souvenirs, T-shirts, and the like. I wondered what they and others working on the site thought of their occupation of what would have been the visiting place for the president of the United States, and what it was like to work in a space built to accommodate administrations—both Filipino and American—whose national legacies have been to suppress the archipelago’s people by way of empire.23 As I looked out to the sky through the half-finished windows, almost Brutalist in the structure’s raw concrete state, I began to consider the ongoing evolution of this People’s Park into the future.

In the park lies a triumphant counter to a long legacy of the kinds of corrupt governments susceptible to Western influence that are typical of postcolonial countries during and after the Cold War. Fanon’s writing again comes to mind: here, on this site, “dreams are encouraged… and the imagination is let loose outside the bounds of the colonial order.”24 The People’s Park in the Sky struck me as an opportunity for Filipinos to gaze upon colonial ruins and, as Filipinos, provide the life of a structure that in the government’s eyes was long dead. While those enjoying its amenities still may suffer from the decisions of a fascist contemporary post-American government, and while the archipelago’s undeveloped mountains can and should be respected as past and potential revolutionary strongholds, the People’s Park makes it clear that when the heavenly gates of empire fall to ruin, the people show up. Fanon continues: “For the native, life can only spring up again out of the rotting corpse of the settler.”25 When the settler is more an institution than a person, a set of unjust principles and –isms that define how the physical world is developed, the unfinished palace is one such decaying structural ideal.

The park has effectively transitioned into what Dipesh Chakrabarty describes as the “History 2” phase on a colonial timeline, in which this mode of cultural reproduction “does not contribute to the reproduction of the logic of capital… [even though they] can actually be intimately intertwined with relations that do.”26 While the Filipinos in the park have created their own opportunities for survival as small vendors in a broader postcolonial system, they are doing so within a spatial and economic subversion of the very system they are surviving. The park’s vendors, those who come to pay homage to the revolution, and everyday visitors coming to enjoy the view all exhibit a life that, beyond refusing to reproduce “the logic of capital,” is filled with an almost mundane joy. I witnessed there an everyday serenity, seeing what seemed to my Americanized eyes a more ideal, collective, contemporary Filipino reality following unjust development. Having myself been born from the wellspring of capitalism that served to deepen injustice in the Philippines, I quietly celebrated the bustling collective life in the People’s Park that survived amid the chaos of foreign wealth, big landlord corporations, and corrupt bureaucracy.

We left the park around 12:00 p.m., an hour or two before the volcano erupted. The eruption covered the park in ash, much like the lowlands surrounding Taal and Tagaytay Highlands, leaving food and souvenir stands in a state of ruin not unlike the mansion itself. However, mere days after Taal’s initial explosion and while still under threat of increasingly hazardous eruption, the park’s vendors came together to clean and maintain the park in an attempt to return to their ways of life. Video coverage of the effort shows them collectively working to wash ash from the roofs and walls of their park, speeding the park’s reopening along.27 Any questions around the park’s name were answered then: an essentially cooperatively run public amenity, it is truly of the people.

It is in this detail we can see that after colonial and postcolonial governments fail, after their structural manifestations of power have violently stamped out the will of the people, and after the people wrest literal palaces from the invisible hands of their oppressors, then begins “the second phase, that of the building-up of the vision… helped on by the existence of this cement which has been mixed with blood and anger.”28 When the cement of empire—the physical manifestation of ongoing economic development, turning again to Martinez—is laid upon the land, the decolonial turn is not to expel it in some attempt to return to indigeneity; rather, it is to reclaim and reorient the infrastructures built on the laboring bodies of the marginalized.

As Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang write, “decolonization is not a metaphor.”29 It is not a metaphor because colonization is, likewise, not a metaphor and continues today in the forms of systems of oppression favoring wealth accumulation and foreign investment over a nation’s people, even during crisis. Colonial architectures are modes of production that hold distinct properties, values, and laws defining the built environment in increasingly complex and clandestine ways; these ways continue to shape the colonial world, from its hill stations to its palaces, and, now, its condominiums. Ironically, it is becoming clearer now, among the ashes and the ruins of colonial society, the ways in which this system continues to break, the ways in which we are viewing “the descent of their last end.” Of course, calamity strikes at random, and sometimes in quick succession. But when the land rears its magmatic head, and the infrastructures and corruptions of the past fail our recovery, what more just, more communal architectures will rise among the ruins we scrub clean?

-

James Joyce, “The Dead,” Dubliners (1914; Urbana, IL: Project Gutenberg, 2019), link. ↩

-

Republic of the Philippines, Department of the Interior and Local Government, “Statement of DILG Sec. Eduardo M. Año on Measures Undertaken in view of Taal Volcano’s Phreatic Eruption,” January 14, 2020, link. ↩

-

Sofia Tomacruz, “Duterte Wants P30-B Supplemental Budget for Taal Volcano Eruption,” Rappler, January 20, 2020, link. Though President Duterte had made steady and significant cuts to the calamity fund, he requested a “supplemental budget” for the emergency, ignoring comments and questions around the past budget cuts. In the current pandemic, he has proposed similar emergency budget expansions, though his COVID-19 response is more military than medical and has drawn increasing criticism from within the Philippines. ↩

-

Reuben Pio Martinez, “As the World Burns,” UPLB Perspective, January 16, 2020, link. ↩

-

Keith Barrow, “Construction Begins on Metro Manila Subway,” International Railway Journal, February 27, 2019, link. ↩

-

“Tagaytay Highlands,” Tagaytay Highlands, accessed March 27, 2020, link. ↩

-

Republic Act No. 4726, Republic of the Philippines, Congress of the Philippines, “An Act to Define Condominium, Establish Requirements for Its Creation, and Govern Its Incidents,” June 18, 1966, link. ↩

-

SM Prime Annual Report 2018 (Pasay, Philippines: SM Prime Holdings, 2018), 2. ↩

-

Amado Guerrero, Philippine Society and Revolution (Hong Kong: Ta Kung Pao, 1971), 114. ↩

-

Iyko Day, Alien Capital: Asian Racialization and the Logic of Settler Colonial Capitalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 8. ↩

-

Day, Alien Capital, 7. ↩

-

Dean Itsuji Saranillio, “Why Asian Settler Colonialism Matters: A Thought Piece on Critiques, Debates, and Indigenous Difference,” Settler Colonial Studies, vol. 3, no. 3–4 (2013): 286. ↩

-

Hill stations across South and Southeast Asia (including a small number in Africa) were colonial wellness retreats for European legislators unused to the heat, humidity, and otherwise non-European climates of the colonies. Hill station culture, architecture, and infrastructure has been written about extensively, from the of-the-era 1948 article “The Hill Stations and Summer Resorts of the Orient,” by J. E. Spencer and W. L. Thomas and published in the October issue of the Geographical Review; to more recent literary analyses of hill stations as setting and context in Alan Johnson’s 2011 book Out of Bounds: Anglo-Indian Literature and the Geography of Displacement; to the numerous geographical, architectural, and ecological analyses of specific hill stations across the world. ↩

-

Samuel E. Kane, Thirty Years with the Philippine Head-Hunters (Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1933), 317–319. The title of this publication is telling of the racist presumption of the Igorot people (alongside, of course, indigenous Filipinos and other indigenous islanders more broadly) as violent, headhunting savages. I expand upon this phenomenon and its imperialist implications below. ↩

-

Rudyard Kipling, “The White Man’s Burden: The United States & The Philippine Islands, 1899,” in Rudyard Kipling’s Verse: Definitive Edition (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1929). See John Bellamy Foster and Robert W. McChesney’s 2003 analysis of the poem in the Monthly Review, articulating the poem’s ongoing legacy of race and American empire, link. ↩

-

David Brody, Visualizing American Empire: Orientalism and Imperialism in the Philippines (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2010), 160. ↩

-

Rebecca Tinio McKenna, American Imperial Pastoral: The Architecture of US Colonialism in the Philippines (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 169–170. ↩

-

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Constance Farrington (New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1963), 39. ↩

-

Diana Jean Sandoval Martinez, Concrete Colonialism: Architecture, Urbanism, Infrastructure, and the American Colonial Project in the Philippines (doctoral dissertation, Columbia University, 2017). ↩

-

Brody, Visualizing American Empire, 144–145. ↩

-

Christopher John Chanco, “Frontier Polities and Imaginaries: The Reproduction of Settler Colonial Space in the Southern Philippines,” Settler Colonial Studies, vol. 7, no. 1 (2017). ↩

-

Janet Cawley, “Marcos’ Mountain Palace Is the House that Arrogance Built,” Chicago Tribune, March 30, 1986, link. ↩

-

After Spanish rule, a revolutionary government called the First Philippine Republic was established. After it was made clear that the US would not recognize it as a legitimate government, the Philippine–American War broke out, lasting from 1899 to 1902. Estimated civilian deaths as a direct result of the Philippine independence movement range from 200,000 to 1 million. An estimated 4,000 to 6,000 American soldiers were killed, while anywhere between 16,000 to 20,000 Filipino independence fighters were killed. ↩

-

Fanon, Wretched of the Earth, 68. ↩

-

Fanon, Wretched of the Earth, 92. ↩

-

Dipesh Chakrabarty, “Universalism and Belonging in the Logic of Capital,” Public Culture, vol. 12, no. 3 (Fall 2000): 669. ↩

-

The park was set to reopen only two weeks after the initial eruption; of course, however, conversations around the overall safety and sustainability of living near the volcano would follow. Currently, the COVID-19 pandemic has seen militant, martial-law-style shutdowns throughout the archipelago, with even brief ventures outdoors leading to dire legal and even life-threatening consequences, further disabling the park’s vendors. ↩

-

Fanon, Wretched of the Earth, 93. ↩

-

Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, vol. 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–40. ↩

Patrick Jaojoco is an independent curator, researcher, and organizer focusing on the long-term spatial implications of colonialism and decolonization. He is an organizer of the Decolonial Mapping Toolkit, a project that attempts to decolonize mapping processes by reframing colonial histories in public space, and has written for Artforum, the Brooklyn Rail, and numerous exhibition catalogs. Patrick is a 2020 AICA Art Writing Workshop participant and a member of NEW INC at the New Museum.