On July 12, 2020, I was lying on my couch, catching up on the twitterverse, when I came across a video. Hundreds of people were squished together, rager style, without masks, swaying to a song you couldn’t hear. I rolled my eyes thinking it was some college party, complete with guys in backward hats and “bro tanks,” oozing with heteronormative masculinity. I checked the caption and choked on my iced coffee. “Independence Day party video of US soldiers, rumored to be the cause of a cluster… #沖縄 #コロナ.”1

Hashtag Okinawa.

Hashtag Corona.

Okinawa Prefecture, the political unit that comprises most of the former Ryûkyû Kingdom, is a chain of hundreds of small islands between Japan and Taiwan and “home” to roughly half of the US service personnel stationed in Japan.2 On July 7, 2020, US Marines informed the Okinawa Prefectural Government that a coronavirus cluster had been identified at a particularly contentious base: Marine Corps Air Station Futenma.3

MCAS Futenma has for years been what Dustin Wright has called “the lodestone for Okinawan frustration.”4 The base first came under deep scrutiny after the now-infamous 1995 kidnapping and rape of a twelve-year-old Shimanchu girl by three American servicemen.5 In 2003, then-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld deemed Futenma “the most dangerous base in the world,” in no small part due to its location in the densely populated city of Ginowan.6 Frustration over MCAS Futenma, however, can be isolated not only to Futenma itself but also to the planned construction of the Futenma Replacement Facility (FRF) in Oura Bay, Henoko.

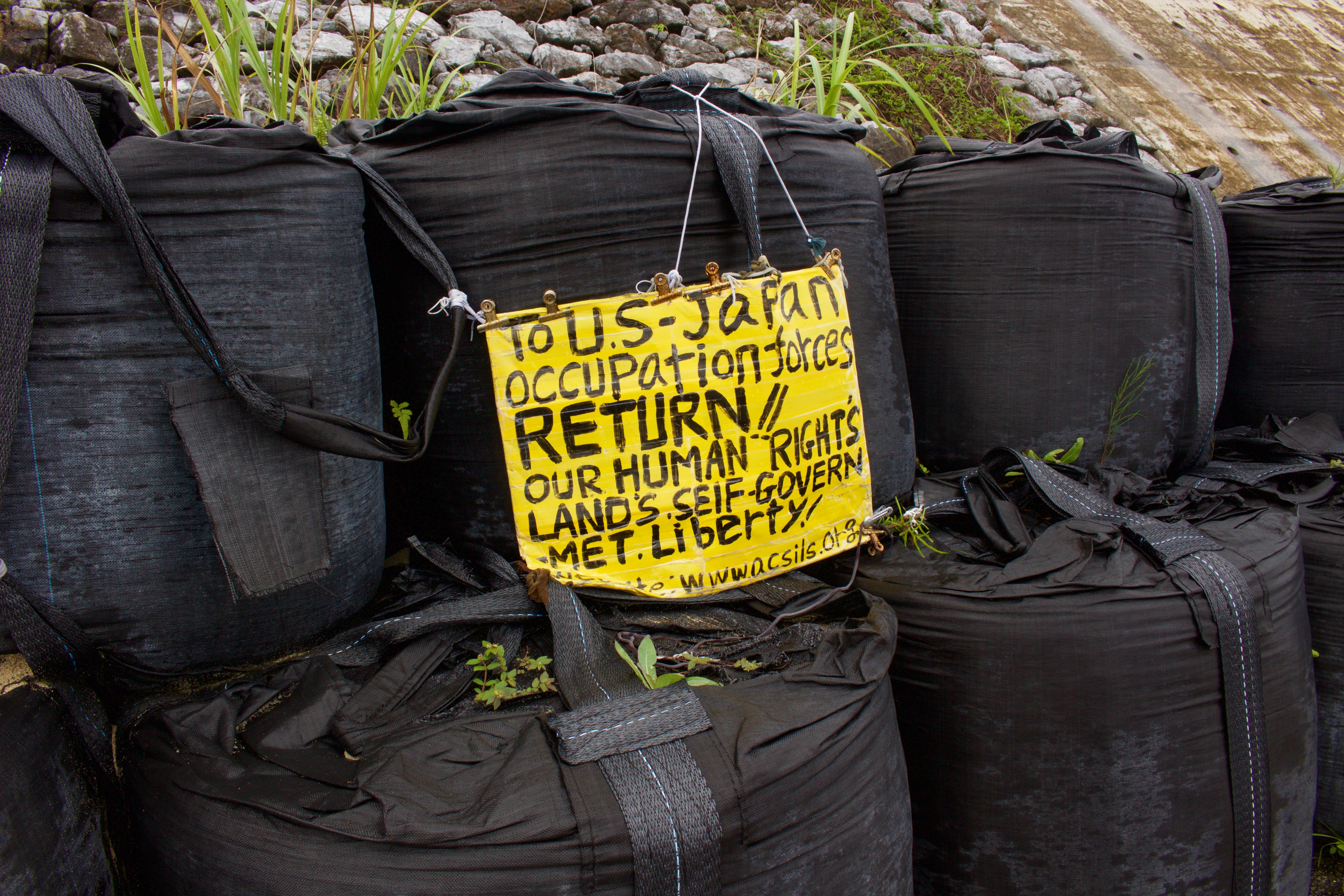

The ire surrounding MCAS Futenma and its planned relocation in Henoko has been the result of years of accidents, crime, and the undermining of Shimanchu self-determination—evidenced most recently by the Japanese government’s skirting of the results of a nonbinding referendum that voted in heavy opposition to the construction of the new base. In a recent survey conducted by the Ryûkyû Shimpo, Okinawa Television Broadcasting, and JX News Agency, 61 percent of the 502 respondents at least somewhat opposed the construction of the FRF in Henoko; in February 2019 a Prefectural Referendum resulted in a resounding “No” vote against the construction of the FRF in Henoko, with 70 percent of voters opposing the plan.7

The history of land seizure by the United States via “bayonets and bulldozers,” the high concentration of US soldiers in the Ryûkyûs, and the continued protests against the current and future base (which have continually been ignored by the Japanese central government) position Futenma and the FRF squarely within the realm of so-called Indigenous issues.8 However, while Shimanchu indigeneity is not a question of this paper, it should be noted that while the United Nations recognizes the “Ryûkyû/Okinawa” (Shimanchu) people as Indigenous, the Japanese government does not.

Futenma and the Futenma Replacement Facility Plan

The US military presence in the Ryûkyû islands has been a long-standing point of contention for the Shimanchu people. Self-determination for the Shimachu is often undermined by Japan to facilitate a good relationship with the US military, the most recent of which is the result of a twenty-plus-year plan to construct the FRF. In 1996, the Japanese and US governments, as part of the Defense Policy Review Initiative, agreed to relocate MCAS Futenma out of Ginowan and to Henoko in the northern part of Uchinaa (Okinawa island).9 Despite its intent to move Marines to a less densely populated part of the island, the provisional decision drew controversy because it maintained force levels within the prefecture and did not transition them elsewhere in Japan. In 1997, the City of Nago, where Henoko is located, voted no against the project in a local nonbinding referendum.10 The project continued to be unpopular, sparking continual protests at Camp Schwab, the existing base in Henoko.

In 2006, the two countries passed the “Realignment Roadmap,” a formal plan to construct the FRF in Oura Bay and to transform Camp Schwab into a large-scale Marine Corps Air Station. While meeting some local demands, the plan outlined a way to downsize US military forces in Okinawa as a whole, proposing to send some Marines to Guam and eventually return land from older bases, contingent, however, on the completion of the FRF.11 According to the Realignment Roadmap, construction at Camp Schwab was targeted for completion by 2014.12

In 2011, actual construction in Oura Bay had yet to begin, but the Security Consultative Committee—a group consisting of the US Secretaries of State and Defense and the Japanese Ministers of Foreign Affairs and State of Defense—issued a statement reasserting the project’s importance. This time, emphasizing “the increasing importance of the presence of the US forces in Japan, including in Okinawa, to maintain deterrence and strengthen Alliance capabilities in view of the current evolving regional security environment.”13 By this time, the long-standing dispute between China and Japan over the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands was reaching a boiling point, and the United States had recently engaged in Operation Tomodachi to provide aid to Japan following the tsunami and subsequent Fukushima nuclear disaster. In 2012, the Security Consultative Committee issued a follow-up statement maintaining that,

The ministers resolve to continue to work toward the relocation of MCAS Futenma in a way that meets the criteria: operationally viable, politically feasible, financially responsible, and strategically sound. The Ministers reconfirmed their views that the FRF, planned for construction at the Camp Schwab-Henoko saki area and adjacent waters, remains the only viable solution that has been identified to date.14

The reports did not explain how Camp Schwab’s expansion came to be viewed as the “only viable option” given increasing opposition from the local population and the existence of an additional airfield (Kadena Air Force Base) already in Okinawa and the disproportionately high number of bases and US servicemen already in the Ryûkyûs.15 By 2016, 70.6 percent of sole-use American military installations and bases in Japan were located in Okinawa Prefecture, despite being 0.6 percent of Japan’s total landmass.16 In 2020, Uchinaa and its satellite islands hosted one-eighth of all American troops stationed abroad, on a total of thirty-one installations.17

Shimanchu as an Indigenous Identity

Indigenous identity in the Shimanchu context is complex and not a given within the Shimanchu community itself. Laura Kina, a mixed-race Okinawan (Uchinaanchu)-American, articulates the nuance of “discovering” Shimanchu as an Indigenous identity:

I remember being surprised at Taulapapa McMullen’s [a Samoan American fa’afafine (third-gender) artist] explanation that Okinawans are Indigenous because we were the original inhabitants of the Ryûkyû Islands and our traditional language, culture, and land have since been colonized by Japan and the US.18

Kina’s surprise is not an isolated experience and is further complicated by the linguistic connotations of indigeneity as well the numerous labels and identities Shimanchus can hold simultaneously. Whether it’s because, as Ryan Masaaki Yokota, Richard Siddle, and others have noted, the Japanese term for Indigenous, senju minzoku, is historically linked to connotations of “backwardness,” or because, as Kina notes, it is seen as a highly politicized subject position, self-identifying as “Indigenous” is not universal among the Shimanchu community.19 In an English-language conversation with a person of Japanese descent, my own identification as “Indigenous Ryukyuan” led to guffaw and confusion: Why was I was differentiating myself from “other Japanese”? Why was I, by reiterating that I was Ryukyuan and NOT Japanese, creating an unnecessary and uncomfortable distinction between these two identities?

Activist Oyakawa Shinako, in a 2019 interview, relayed a similar experience: “We had a lot of criticism, especially from Japanese scholars, like, ‘oh, you’re discriminating against Japanese people.’ Or, ‘you’re too nationalistic; that’s not good.’ And I always say, our nation was taken by you. So how can we be nationalistic?”20 Kina’s observation, Oyakawa’s experience, and my conversation are not unusual for Shimanchu Indigenous advocates, and a 2019 study of millennial Okinawans (in the Prefecture) from the East-West Center goes so far as to say that “Okinawans feel more Japanese than ever.”21 This is not to say that Shimanchus (Uchinaanchus in the “Millenial+” report) do not experience an outsize level of pride in Okinawan identity; the study also found that “Okinawan or ‘Uchinanchu’ is a powerful and exclusive identity… when we discussed with older Okinawans, some commented that the sense of Okinawan pride has been growing, not just within Okinawa itself but throughout the Okinawan diaspora… We know of no other Japanese prefecture with this level of local identity.”22

The articulation of “Okinawan” as merely a strong local identity plays down the unique history of the Ryûkyû islands, which is unlike any other Japanese prefecture. Today’s Okinawa Prefecture, the ancestral homeland of Shimanchu people, was formerly the Ryûkyû Kingdom until it was annexed by Japan in 1879. Though nominally never a colony, the Ryûkyûs were governed akin to one, with Shimanchus undergoing processes of dōka and kōminka, assimilation and imperialization, respectively. In understanding Ryukyuans as different from Japanese, two Shimanchu women, Nakamura Kame and Uehara Ushi, were displayed in the Human Pavilion at the Fifth Industrial Exhibition in Osaka in 1903, alongside other Japanese imperial subjects.23 During World War II, one third of Uchinaa’s population was killed during the Batlle of Okinawa.

Okinawa Prefecture once again became called “The Ryukyus” during the formal US occupation from 1945–1972; it was during this period that the mass construction of US bases in the Ryûkyûs occurred, the majority of which are still operating today. Shimanchu pride is unique because the Ryûkyû’s history is unique, especially in regard to the US bases. As articulated in the Millenial+ report: “there is a strong sense of distinct identity and local pride that appears to be frequently coupled with a resentment narrative that Okinawa is under-appreciated by the rest of Japan, as demonstrated by the heavy concentration of foreign bases.”24

Pride in a strong Okinawan or Uchinaanchu identity however, does not equate to a self-proclaimed indigenous identity. Further, the use of Uchinaanchu and Okinawa can be problematic in that it ties belonging to the Ryûkyû’s largest island (Uchinaa/Okinawa). As a diaspora, Shimanchus are spread across the globe, with major hubs in Japan, Hawai‘i, Brazil, Latin America, and the United States. Within the diasporic population, there have recently been efforts to push for a more inclusive label that ties the island chain together rather than defer to the main island of Uchinaa. Shimanchu, or people of the (Ryûkyû) islands, is the result of that push for inclusivity.

My use of Shimanchu here expresses a pride in my identity as Uchinaanchu, as my family is, in fact, from the island of Uchinaa, and works to strongly anchor my identity to an Indigenous one with direct ancestral ties to the Ryûkyû islands at large. I employ the term “Shimanchu”—“island” (shima) “people” (chu)—when referring to myself and other Ryukyuans/Okinawans/Uchinaanchus in Okinawa Prefecture or in the diaspora, as a way to emphasize our ancestral connection to the Ryûkyû islands but also connectivity between our islands.

Derived from a conversation with Eric Wada, who has been at the forefront of normalizing the use of Shimanchu, Kina explains, “this shift to using the Uchinaaguchi word in place of the English word ‘Indigenous’ also shifts our thinking to how a person is dependent on the island and of the island.”25 Such a shift in Indigenous identity from a continentally oriented one to that of an island perspective has simultaneously put Shimanchu Indigenous issues into larger conversation with Indigenous issues throughout the Pacific, namely in Hawai‘i and Guåhan, which are also marked by deep legacies of US militarization.26 As Kina recalls of her conversation with Taulapapa McMullen, while a continental perspective posits islands and their people as peripheral within nation-states, Oceanic perspectives fundamentally show islands and their people as connected through waterways and their possibilities.27

Dual Colonialism and the Ryûkyûs

Just as naming and adopting a consolidated Indigenous identity is complicated for Shimanchus, the colonial situation of the Ryûkyûs is equally complex. Though nominally not a colony, the state of Okinawa Prefecture today needs to be categorized as dually colonized by both the United States and Japan. Following World War II, Okinawa Prefecture became the “Keystone of the Pacific” for the United States military and was severed politically from Japan until 1972. The exponential increase in US bases in Ryûkyû during the US occupation period (1945–1972), coincided with an exponential decrease of bases on the Japanese mainland.28

Annmaria Shimabuku points out that: “the vast majority of research critical of the Okinawan situation either focuses on one side at the expense of ignoring the other… or attempts to transcend the problem through a ‘universal’ approach.”29 Instead of focusing only on Japan or the US, Shimabuku posits that the Ryûkyûs are subject to transpacific colonialism at the hands of both nations. She articulates that, “insofar as nation-states are mutually vested in suppressing their ethnic minorities, this approach enables me to open up a space for the convergence of minority politics in both the American and Japanese state contexts.”30 This framework serves to better explain the complicated space that Okinawa presently occupies: an independent country until 1879, controlled by the United States Civil Administration of the Ryûkyûs from 1945–1972, and currently governed by Japan in an arrangement that tacitly allows for occupation by the US military.

The disproportionate number of US servicemen and bases on Uchinaa specifically and in Okinawa Prefecture generally have been the cause for protest by Shimanchus against the bases themselves, with sit-ins at Camp Schwab for over two thousand days, and against the Japanese central government and particularly the LDP.31

Shimanchus and the United Nations

In April of 2018, Oyakawa Shinako sat on a dais in the Indigenous Media Zone and delivered a statement on behalf of the Ryukyuan delegation to the Seventeenth Session of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues:

Because of Japan’s annexation and colonization, we Ryûkyû people have become a stateless minority and have been subject to discrimination and subordination. The Ryûkyû islands account for only 0.6% of so-called Japanese territory but we unwillingly host more than 70% of the US military bases in Japan. Moreover, both the Japanese and US governments are violently pushing through with construction of new military bases at Henoko [the Futenma Replacement Facility] and Takae, in the northern part of Okinawa island in Ryûkyû. The situation now is that we are not recognized as indigenous people, even though the UN encourages and wants the Japanese government to recognize us as indigenous people and protect our rights, but the Japanese government says “no, there is no such thing as Ryûkyû indigenous people, so there is no discrimination towards you.”32

Self-determination has been a long-standing concern of the United Nations, as shown in international doctrines like the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the UN Declaration on the Rights on Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).33 While Japan ratified the UNDRIP in 2007 and recognized the Ainu people as Indigenous in 2008 (and again in 2019), it has continually rebuffed the UN’s recommendation to recognize the “Ryûkyû and Okinawa” as Indigenous.34 Most recently, in 2018, the UN issued the periodic report on Japan issued by the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, which stated:

The committee is concerned that the Ryûkyû/Okinawa are not recognized as Indigenous peoples despite its previous recommendation and recommendations from other human rights mechanisms. The Committee is also concerned at…challenges reportedly faced by the Ryûkyû/Okinawa peoples related to accidents involving military aircraft in civilian areas, owing to the presence of a military base of the United States of America.35

In spite of Japan’s insistence on the contrary, legal scholar Uemura Hideaki asserts, “we must be reminded that peoples who were unilaterally, and by-force, annexed to the territory of a given nation-state as an unrecognized colony are called ‘indigenous peoples’ by the currently accepted definitions of international law.”36 Uemura’s understanding of Shimanchus as Indigenous despite lacking governmental approval aligns with definitions provided by Indigenous scholars. Linda Tuhiwai Smith, in her canonical work Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, articulates another framework for understanding Shimanchu indigeneity, and the Shimanchu struggle against Futenma and its expansion as anti-imperialist:

Legislated identities which regulated who was an Indian and who was not, who was a metis, who had lost all status as an indigenous person, who had the correction fraction of blood quantum, who lived in regulated spaces of reserves and communities, were all worked out arbitrarily (but systematically), to serve the interests of the colonizing society.37

Smith’s argument set forth in Decolonizing Methodologies has put to words what Indigenous peoples have known for centuries: that identities legislated as Indigenous or not by governments have always been politicized for the benefit of the colonizer’s agenda. Thinking with Uemura’s and Smith’s definitions of indigeneity—or, in Smith’s case, about the illegitimacy of having an Indigenous identity be legislated by the colonizer—means recognizing that whether or not Shimanchus are Indigenous cannot be accurately or ethically determined by the very nation-states that are “mutually vested in suppressing their ethnic minorities.”38 Shimanchu indigeneity cannot be questioned for the sole reason that the nation-state of Japan does not see them as such.

Shimanchus are represented at the United Nations and have been since 1996 when Shimanchu delegations began to participate in the Working Group on Indigenous Populations.39 As Ryan Masaaki Yokota articulates, it could even be said that Shimanchu “identity as indigenous emerged out of a recognition of the growing post–World War Two influence of international human rights law.”40

Development of the postwar human rights regime from individual rights to minority rights and eventually to Indigenous rights signaled the inauguration of a new era in which sub-state actors could marshal powerful precedents from international law to impact domestic administrative and legislative actions.41

In the postwar period, international law and the emergence of international governance by bodies like the UN framed how Shimanchus articulated their indigeneity on the world stage. Today, Shimanchu expressions of indigeneity cannot be de-linked from struggles against the militarization of the Ryûkû Islands.

Like Oyakawa’s statement, which made visible the ongoing violence of militarization, recounting the numerous rapes, murders, and military vehicle crashes that have resulted from the US’s presence, Special Rapporteur Doudou Diène underscored the pervasiveness of the US military in the daily lives of many Shimanchu.42 In his 2006 report on Contemporary Forms of Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia, and Related Intolerance for the Mission to Japan, he stated:

The most serious discrimination they [Shimanchus] presently endure is linked to the presence of the American military bases in their island. The Government justifies the presence of the bases in the name of “public interest.” However, the people of Okinawa explained that they suffered daily from the consequences of the military bases: permanent noise linked to the military airport, plane and helicopter crashes, accidents due to bullets or “whiz-bangs,” oil pollution, fires due to air maneuvers, and criminal acts by American military officers. The noise due to airplanes and helicopters is higher than the level prescribed by law and causes severe health consequences.43

Diène’s report articulated the military situation in the Ryûkyûs as the cause of discrimination of Shimanchus in Japan. While not going so far as to call Shimanchus Indigenous at the time, the report did provide a counternarrative to the government’s continued insistence on the nonexistence of discrimination—identifying the people of Okinawa as one of three discriminated-against “national minorities,” which also included the Buraku people and Ainu.44

The consistent issues of military-on-Shimanchu crimes, the concentration of military vehicle crashes in the Ryûkyûs, and the subversion of Okinawan citizens’ political will by continuing the construction of the FRF in Henoko are frequently cited grievances by Shimanchus on the world stage and particularly in Indigenous spaces such as the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues.45 On March 6, 2020, the website for the Nineteenth Session of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues was updated to read, boldly in red: “The 2020 Session of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues has been postponed, until a later date to be determined.”46 For the Shimanchu Delegation, a number of events had transpired in the Ryûkyûs that warranted discussion at the Permanent Forum. Since the 2019 forum in April, a number of high-profile events have happened in Ryûkyû.47 Most critically, perfluorooctane sulfonate and perfluorooctanoic acid had been discovered in high concentrations in the water sources outside of MCAS Futenma and Kadena Air Force Base, construction of the FRF in Oura Bay has continued, and on October 31, 2019, Sui Gusuku (Shuri Castle) was destroyed by fire.48 When news of the fire, in real time, reached the United States, Hawai‘i, and other western hemisphere locations with large Shimanchu diasporas, it was cruelly, ironically, still World Uchinaanchu Day (celebrated October 30).

But for all the issues that the Shimanchu delegation had prepared to delve into at the Permanent Forum, COVID-19 was just beginning to ravage the world. On Instagram, the @un4indigenous account stated that in making the decision to cancel the forum, Members of the Permanent Forum took into consideration “the already precarious health situation that many indigenous peoples live in, and the imperative to avoid adverse impacts.”49 The Ryûkyûs’ large elderly population was particularly at risk in the COVID-19 crisis. Precautions were taken, and by July, Okinawa Prefecture had managed to keep its infection total at 148.

And yet on July 7, 2020, the Okinawa Prefectural government was informed by the Marines that there was a cluster of positive coronavirus cases inside MCAS Futenma.50 By July 13, the number of cases would balloon to ninety-four across several bases, in addition to an off-base hotel temporarily being used to quarantine inbound servicemen (this was later canceled due to public outcry).51 The coronavirus issue, though only one lens through which to look at the tensions surrounding MCAS Futenma, in a moment of global empathy, maybe a way to shift meaningful focus onto Futenma and the ongoing issues in the Ryûkyûs writ large.

-

My translation. @Oshinako, “米兵さんたちが「クラスター」と噂している独立記念日のパーティー動画が回ってきた,” Twitter, July 12, 2020. ↩

-

As a whole, Okinawa Prefecture itself consists of 0.6 percent of the total landmass of Japan. The largest island is Ochinaa. ↩

-

“普天間飛行場で米軍属複数がコロナ感染海兵隊が情報従業員ら足止め” Ryûkyû Shimpo, July 7, 2020. link. ↩

-

Dustin Wright, “Impasse at MCAS Futenma,” Critical Asian Studies 42, no. 3 (2010): 457–468, link. ↩

-

Most of my research is about Uchinaa, the main island of the Ryûkyûs; however, I consciously use the term Shimanchu, meaning “island people,” to encompass the larger identity of the archipelago. Shimanchu here is also purposeful, as “indigenous people” in Japanese does not carry the historical nuance that it has acquired in English, in Ryûkyûs this causes recoil or outright denunciation of the label outside of scholarly contexts. Shimanchu, literally “(Ryûkyûs) island people,” has the capacity to address issues that have come to be seen as “indigenous issues,” such as self-determination, land rights, and preservation of culture and language. ↩

-

Douglas Lummis, “The Most Dangerous Base in the World,” Asia-Pacific Journal 16, issue 14, no. 1 (July 2018): link. ↩

-

“Okinawa Survey Results Show 61 Percent Oppose Henoko Relocation, 18 Percent Support Abe Administration,” Ryûkyû Shimpo, July 17, 2020. ↩

-

“United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples,” ratified September 2007. ↩

-

Marine Corps Installations Pacific, Marine Corps Vision and Strategy 2025 (Arlington: Marine Corps Headquarters), undated. Shimanchu people are not considered Indigenous by the government of Japan, but the United Nations has issued four recommendations to the Japanese government to do so. Shimanchus are internationally recognized as Indigenous. There are a number of articles in the UNDRIP that the Marine Corps and Japanese government would be in violation of Articles 3 and 4 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (the right to self-determination); Articles 26 and 29, the right to traditional land and to conserve and protect the environment, respectively; and, perhaps most critically, Article 30, that “military activities shall not take place in the lands or territories of indigenous peoples, unless justified by a relevant public interest or otherwise freely agreed with or requested by the indigenous peoples concerned.” ↩

-

Kyodo, “Residents Vote ‘No’ to Heliport- Japanese Report,” BBC News, December 21, 1997. ↩

-

Rice, Rumsfeld, Aso, Nukaga, “United States-Japan Roadmap for Realignment,” May 1, 2006. ↩

-

Rice, Rumsfeld, Aso, Nukaga, “United States-Japan Roadmap for Realignment,” May 1, 2006. ↩

-

Clinton, Gates, Matsumoto, Kitazawa, “Progress on the Realignment of US Forces in Japan” (June 21, 2011). ↩

-

Clinton, Panetta, Gemba, Tanaka, “Joint Statement of the Security Consultative Committee” (April 27, 2012), 5. ↩

-

When Nago held its referendum in 1997, 27,000 of the total 47,000 American servicemen in Japan were stationed in the Ryûkyûs. Kyodo, “Residents Vote ‘No’ to Heliport-Japanese Report,” BBC News, December 21, 1997. ↩

-

See United States Government Accountability Office, “Congressional Committees,” Marine Corps Asia Pacific Realignment: DOD Should Resolve Capability Deficiencies and Infrastructure Risks and Revise Cost Estimates (April 5, 2017); and Okinawa Prefectural Government Office Washington, DC, “US Military Facilities and Areas on Okinawa Main Island & its Vicinity,” US Military Base Issues in Okinawa. ↩

-

Reinsch, John, “Let’s Push Democratic Presidential Hopefuls to Address US Bases on Okinawa,” Truthout, December 8, 2019. ↩

-

Laura Kina, “Ancestral Cartography: Trans-Pacific Interchanges and Okinawan Indigeneity,” Asian Diasporic Visual Cultures and the Americas 6 (2020): 48–70. ↩

-

Ryan Masaaki Yokota, “The Okinawan (Uchinānchu) Indigenous Movement and Its Implications for Intentional/International Action,” Amerasia Journal 41, no. 1, (2015): 55–73; Richard Siddle, “Return to Uchinā: The Politics of Identity in Contemporary Okinawa,” in Japan and Okinawa: Structure and Subjectivity, eds. Glenn Hook and Richard Siddle, (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003), 14; and Kina, “Ancestral Cartography,” 68. ↩

-

Oyakawa Shinako, “Interview with Shinako-shinshii 071519,” interview by Lex McClellan-Ufugusuku, July 15, 2019. ↩

-

Steve Rabson, “Being Okinawan in Japan: The Diaspora Experience,” Asia-Pacific Journal 10, issue 12, no. 2 (March 2012), link. ↩

-

Charles E. Morrison and Daniel Chinen, “Millenial+ Voices in Okinawa,” 2019, 12. Charles E. Morrison and Daniel Chinen, “Millenial+ Voices in Okinawa: An Inquiry into the Attitudes of Young Okinawan Adults Toward the Presence of US Bases,” 2019, link. ↩

-

Kirsten Ziomek, Lost Histories: Recovering the Lives of Japan’s Colonial Peoples (Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, 2019): 37. Ziomek’s interrogation of Nakamura and Uehara’s display in the pavilion and its potential gray area is outside the scope of this paper but definitely worth a read nonetheless. ↩

-

Morrison and Chinen, “Millenial+ Voices in Okinawa,” 2019, 5. ↩

-

Kina, “Ancestral Cartography,” 68. ↩

-

John Letman, “Native People Across the Pacific Are Resisting Dispossession of Sacred Land,” Truthout, August 6, 2019, link. ↩

-

Kina, “Ancestral Cartography,” 59. ↩

-

Annmaria Shimabuku, Alegal: Biopolitics and the Unintelligibility of Okinawan Life (New York: Fordham University Press, 2019), 37. ↩

-

Shimabuku Annmaria. “Transpacific Colonialism: An Intimate View of Transnational Activism in Okinawa,” The New Centennial Review (2012): 131. ↩

-

Shimabuku, “Transpacific Colonialism,” 132. ↩

-

“Okinawa Survey Results Show 61 Percent Oppose Henoko Relocation, 18 Percent Support Abe administration,” Ryûkyû Shimpo, July 17, 2020. ↩

-

“Indigenous Human Rights Defenders and Land Rights in Asia—Indigenous Media Zone,” moderated by Gam A. Shimray, UN Web TV, April 18, 2018, video, 24:45, link. ↩

-

“International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,” entered into force March 23, 1976; “United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples,” ratified September 2007. ↩

-

Translation of diet resolution from: Ito Masami, “Diet Officially Recognizes Ainu as Indigenous,” Japan Times, June 7, 2008. ↩

-

International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, “Concluding Observations on the combined tenth to eleventh periodic reports of Japan,” Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discimination, September 26, 2018. ↩

-

Hideaki Uemura, “The Colonial Annexation of Okinawa and the Logic of International Law,” Japanese Studies 23, no. 2 (2003): 122. ↩

-

Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, Second Edition (London: Zed Books. 2012), 23. ↩

-

Shimabuku, “Transpacific Colonialism,” 132. ↩

-

Masaaki Yokota, “The Okinawan (Uchinānchu) Indigenous Movement," 59. ↩

-

Masaaki Yokota, “The Okinawan (Uchinānchu) Indigenous Movement,” 55. ↩

-

Masaaki Yokota, “The Okinawan (Uchinānchu) Indigenous Movement,” 55. ↩

-

The issue of military-related crime and crashes in the Ryûkyûs has since been reported to the United Nations, including in a 2012 joint statement by the International Movement Against All forms of Discrimination and Racism and the Association of the Indigenous Peoples in the Ryûkyûs (NGOs in special consultative status). The 2012 statement reported “1545 cases of accidents caused by the US military or its personnel… between 1972 and 2010 (annual average about 41 cases). They include 43 cases of aircraft crash, 367 cases of forced (or crash) landing and 520 cases of fires.” This in addition to 5,705 arrests of military personnel for the same period. From General Assembly, “Joint written statement submitted by the International Movement Against All Forms of Discrimination and Racism (IMADR), the Association of the Indigenous Peoples in the Ryûkyûs (AIPR), non-governmental organizations in special consultative status,” Human Rights Council, September 5, 2012. ↩

-

Economic and Social Council Commission on Human Rights, “Report of the Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia, and related intolerance, Doudou Diene: MISSION TO JAPAN,” Commissions on Human Rights (January 24, 2006): 14. ↩

-

Economic and Social Council Commission on Human Rights, “Report of the Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia, and related intolerance,” 2. ↩

-

“「琉球民族」自決権認めて,” Okinawa Times, April 26, 2019. ↩

-

“UNPFII Nineteenth Session: 13–24 April 2020 [POSTPONED],” link. ↩

-

These events also include the Henoko Environmental Oversight Committee suggesting that the Okinawa dugong was “highly likely extinct” (October), a window falling off of a CH-53 helicopter from MCAS Futenma (August), as well as an object falling from a helicopter, also from Futenma, and crashing onto the grounds of Uranishi Junior High (June). See “Henoko Environmental Oversight Committee Specialist Says Okinawa Dugong is ‘Highly Likely Extinct’; Large-scale Survey Needed,” Ryûkyû Shimpo, October 13, 2019; “Window Falls from Futenma Air Station CH-53 Helicopter Over East China Sea Off Okinawa Island,” Ryûkyû Shimpo, August 29, 2019; and “Dangers of MCAS Futenma Not Limited to Ginowan, Helicopter’s Blade Tape Falls onto Uranishi Junior High,” Ryûkyû Shimpo, June 6, 2019. ↩

-

Simon Denyer and Akiko Kashiwagi, “On Japan’s Okinawa, US Military is Accused of Contaminating Environment with Hazardous Chemical,” Washington Post, May 24, 2019. Chie Tome, “OPG Finds High PFOS Concentrations Near Kadena Air Base, Advises Against Drinking the Aater,” Ryûkyû Shimpo, August 24, 2019. “Shuri Castle’s Main Hall and North Hall Completely Burned Down with Fire Spreading to Other Buildings,” Ryûkyû Shimpo, October 31, 2019. ↩

-

Un4indigenous @un4indigenous, “The Members of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues have decided to postpone its forthcoming 19th session,” Instagram photo, link. ↩

-

“普天間飛行場で米軍属複数がコロナ感染海兵隊が情報従業員ら足止め” Ryûkyû Shimpo, July 7, 2020. link. ↩

-

Motoko Rich, Makiko Inoue and Hikari Hida, “Coronavirus Outbreak at US Bases in Japan Roils an Uneasy Relationship” New York Times, July 13, 2020, link. Dave Ornauer and Aya Ichihashi, “Marine Corps on Okinawa Nixes Inbound Stays at Off-base Hotels After Coronavirus Surge,” Stars and Stripes, July 14, 2020. ↩

Alexyss (Lex) McClellan-Ufugusuku is a PhD student in the department of history at the University of California–Santa Cruz. She has represented the Ryûkyûs at the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues and serves on the executive team of the Okinawa Memories Initiative at UCSC. In her free time, Lex coaches intercollegiate women’s and high school boys’ lacrosse in Santa Cruz, California.