Let’s begin with the facts. The latest available information on the American prison population suggests that there are almost “2.3 million people in 1,833 state prisons, 110 federal prisons, 1,772 juvenile correctional facilities, 3,134 local jails, 218 immigration detention facilities, and 80 Indian Country jails as well as in military prisons, civil commitment centers, state psychiatric hospitals, and prisons in the U.S. territories.”1 Forty percent (approximately 920,000) of these 2.3 million incarcerated people are Black Americans even though Black Americans comprise roughly 13 percent of the national population.2 In light of the nation’s most recent racial reckoning in a long history of attempts to recognize, confront, and reconcile anti-blackness in every facet of American life (1919 Chicago; 1921 Tulsa; 1964 Harlem, Rochester, and Philadelphia; 1968 Chicago, Washington D.C., and Baltimore; 1992 Los Angeles; 2014 Ferguson; 2015 Baltimore), the discipline of architecture is increasingly called to confront its own anti-blackness and white supremacy.3

Despite the attention returned to the racial dimensions of incarceration and architecture by recent events, there has long been a limited if often abortive desire within architectural practice and education to address the broader ethics of prison design. It was only at the close of 2020, following months of political action in the wake of the murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd, among others, that the American Institute of Architects (AIA) reexamined its Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct, agreeing to adopt an amendment proposed five years earlier by the nonprofit Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR) prohibiting AIA members from participating in the design or construction of solitary confinement cells or death chambers.4 In 2015, the AIA initially rejected ADPSR's proposal on the grounds that “members with deeply embedded beliefs will avoid designing those building types and leave it to their colleagues…”5 One reading of this unaffected response is a willingness to abdicate professional responsibility for the well-being of a broadly imagined social group and to instead primarily focus on how “architects practice, treat each other, [and] perform in the eyes of our clients.”6 This implies that both architects and their clients are select and discrete social groups, whose racial, sexual, and economic concerns do not overlap with those of incarcerated populations. Another possible reading is that it is not the aim of the profession nor the place of its governing bodies to promulgate particular political positions. However, this presumes that professionalization has not been racialized and that architecture and politics are in some way separable; as if the work of architects who choose to design death chambers, solitary confinement cells, or prisons more broadly—an architecture emblematic of racial injustice—does not inform the political standing of the profession at large, nor does the profession’s politics inform or sanction the choices of its individual members.

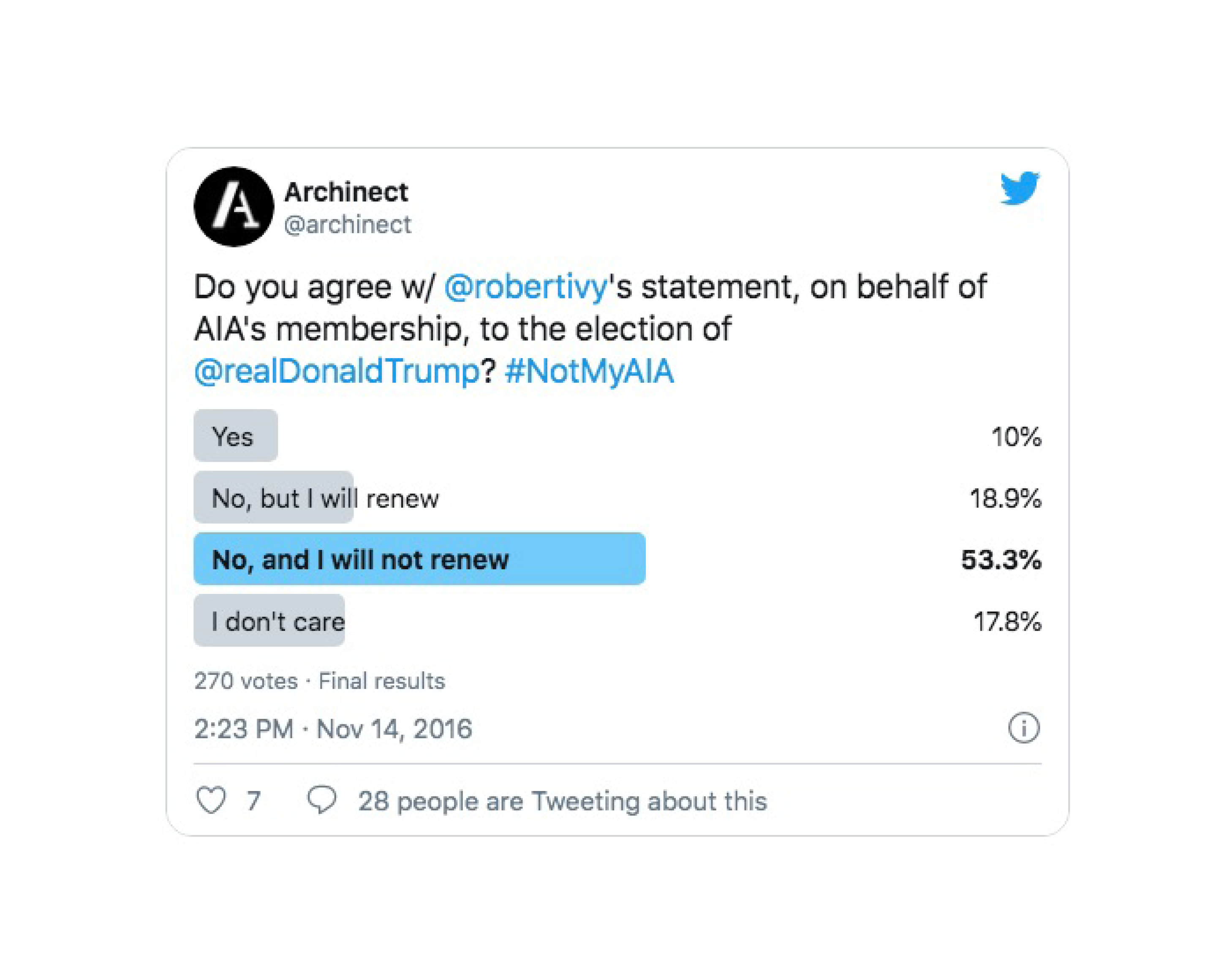

This second reading of this statement was ironically given the lie in 2016 when the AIA drew the “ire” of many members after its executive vice president and CEO, Robert Ivy, released a memo stating the AIA was committed to working with then President-elect Donald J. Trump and his administration. Overlooking the multiple forms of blatant bigotry that formed the foundation of the Trump campaign, Ivy’s memo solely focused on the $500 billion Trump promised to spend on schools, hospitals, and other public infrastructure.7 Yet, given the uniquely explicit and bombastic rhetoric of the Trump campaign, the AIA found it harder to separate politics from professional practice as many members recoiled at any appearance of official support for Trump; for a brief period #NotMyAIA paralleled #NotMyPresident.8

The discrepancy between the general silence around the AIA’s initial rejection of ADPSR’s petition and the visceral backlash to Ivy’s memo raises the question of why a rhetorical form of injustice—although Trump unfortunately put his rhetoric into practice—was treated as more immediately objectionable than ongoing material and racial injustices? On the one hand, members of the profession recoiled at even the appearance of being tied to the American anti-blackness and bigotry embodied by Trump or Trumpism.9 Yet, on the other hand, the AIA's rhetoric of individual choice and ADPSR’s focus on particular building elements (death chambers and isolation cells) and, ironically, the well-being of a broadly imagined social group (human rights), tacitly perpetuated and co-produced structures of anti-blackness in their colorblind pursuit of respectability.10 Because the AIA and ADPSR avoided questioning the respectable façade of the profession, efforts at urgently assessing and transforming the practices considered professionally acceptable were channeled into designing more humane prisons, or “good” prisons, rather than sincerely reflecting upon the abolition of mass incarceration or the inequalities that it is both predicated upon and reinforces. As Ivy’s actions and the AIA’s delay in changing its Code of Ethics show, architects and the architectural profession have frequently concentrated more on the appearance of progress, social renewal, and utopian visions at the cost of sincere pursuits for systemic transformation, creative imagination, or material betterment. Instead, conservative approaches that avoid risking the profession’s relationship to power and capital have prevailed, leading to timid incrementalisms, such as “ethical” or “good” prisons, which often cede to pragmatic compromises that preserve inequalities in the built environment for many. Yet let us be clear, no amount of “ethical” design approaches can justify mass incarceration and anti-blackness in the American legal system.

The Non-Prison Prison Studio

I’ve personally spent only one night in jail… I didn’t like it very much.

— Frank Gehry11

High-profile instances of this incrementalism were modeled in two studios run by renowned architect Frank Gehry at the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc) and the Yale School of Architecture (YSOA) in the spring and fall of 2017, respectively.12 Both studios partnered with Impact Justice, other nonprofits/activist groups, and well-funded charitable foundations in attempts to “reimagine” the role of prisons and their design. Whether in response to the profession’s increased awareness of mass incarceration, the Trump administration’s nascent efforts at criminal justice reform, or simply a charitable thematic, these studios aimed to connect carceral architecture to systemic racism—putting architectural education in conversation with critical race theory through Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow as required reading. Students were asked to create new spaces of incarceration while also encouraged to develop individual approaches or design languages for addressing carceral “design problems.”13

The studios themselves should be given the benefit of the doubt for being sincere attempts to potentially inspire architecture students to think differently about design’s complicity in the criminal justice system by connecting them with activists and individuals actively living and addressing the issue of mass incarceration. Yet, what SCI-Arc and YSOA’s incredible amount of media production around these studios shows is a self-consciousness about the fact that they are emphatically not the norm.14 Rather than signaling a progressive turn in architecture education, the absence of similar studios on issues of mass incarceration or systemic racial injustice from either school’s curriculum was not conspicuous but so typical as to appear natural.15 Amid the flowery language and generic spatial descriptions, it seems almost as though the intractable issue of architecture’s role in mass incarceration has been dealt with and resolved. In reality, these educational institutions are effectively endorsing a pragmatist view, one in which it is not only normal and acceptable but laudable for students and architects in the US to design “good” prisons. Short of contemporizing Guillaume-Abel Blouet’s 1843 Projet de Prison Cellulaire, the premise of these studios suggests that such a thing as a “good” prison exists. Such suggestions fall short of addressing racial and class discrepancies in why or how people end up in prisons and what role the broader built environment has in the production and maintenance of the structural conditions underwriting mass incarceration and systemic racism.16 By focusing on remediating the symbolic end of the criminal justice pipeline, other elements of the criminal justice system and more subtle forms of injustice are backgrounded in such a way that they are rendered not objects of design, or their design is not rendered “problematic.” This comes across most directly in the lack of specificity and contorted neologisms used when designs and design conditions are discussed and represented in Gehry’s studio reviews. Those captive in today’s prison system are “incarcerated-residents”—dignified individuals who are not quite citizens but are free to roam a regulated area of the non-prison prison designed for the development of the self-entrepreneurial but un(der)paid laborer—and are represented as abstract and socially neutered 3D-printed metallic figures.17 Just take the following statements featured in SCI-Arc’s promotional video:

STUDENT: …the classrooms are all above, elevated, and wrapped down around the building, and then there are also art studios, a large library, and then retail and restaurants—all of the residences have balconies with rooftop garden space.

CRITIC: This is maybe a place where corrections has plenty to learn from contemporary architecture. A lot of contemporary work has to do with topology rather than topography and how you get surfaces to perform in different ways.

STUDENT: There is a chance here that we can have a system that is about entrepreneurship, about the development of individual [sic].

CRITIC: It should be like that, I mean this is what we do, we aspire to do something better, It cannot be done any other way!18

Remove any references to the criminal justice system from the above statements and it would be unclear whether faculty, students, and critics are describing a prison or a more generalized urban scheme. This ambiguity, however, points to both the success and failure of Gehry’s prison studios’ representations. They serve as an indictment of the discipline of architecture in its inability to be specific about the typology of the prison, perhaps an ongoing legacy of Bentham, or to imagine social relations beyond the unit of the individual. At the same time this lack of specificity shows that issues of systemic racism and injustice are endemic to the entire field of architecture and the built environment. Further, to address such issues would immediately call into question the relationship of architecture to engrained systems of capital and power with all of their racialized and anti-Black dimensions. While the studios offered sincere attempts to connect architecture and design with issues of mass incarceration and racial injustice, they overemphasized reform at the criminal justice system’s (presumable) end. Rather than focusing on the end of this pipeline, and short of spiraling into the irresolvable contradictions of a disciplinary aporia, it is important to find and interrogate the sites in which these relationships between architecture, capital, power, and in/justice are actively articulated, symbolized, and codified. Courthouses offer one such site that is also a critical apex of these relationships.

Building Justice: Courthouses and Enclosures

Before the law sits a gatekeeper. To this gatekeeper comes a man from the country who asks to gain entry into the law. But the gatekeeper says that he cannot grant him entry at the moment. The man thinks about it and then asks if he will be allowed to come in sometime later on. “It is possible,” says the gatekeeper, “but not now.” The gate to the law stands open, as always, and the gatekeeper walks to the side, so the man bends over in order to see through the gate into the inside. When the gatekeeper notices that, he laughs and says: “If it tempts you so much, try going inside in spite of my prohibition. But take note. I am powerful. And I am only the most lowly gatekeeper. But from room to room stand gatekeepers, each more powerful than the other.

— Franz Kafka, “Before the Law”19

From its inception, the American judicial system was spatially predicated on a conception of enclosure; that there was a space in which justice occurred that was physically and symbolically separated from other aspects of everyday life, and consequently could be rendered exclusive along lines of race, gender, class, and profession.20 Continuing this relationship with wealth and property, courthouses in early Colonial America were frequently located not in trading centers but near the geographic center of a county or the intersection of major thoroughfares between collections of white landowners.21 These freestanding structures required those petitioning or summoned by the court to arrive at the designated location on set days, at set times, and to conduct their actions within specific procedures—in other words, to perform, what Michel Foucault identified as the correlation between the law, the body, and its gestures in an age of sober punishment.22 In doing so, these structures helped construct a normative system of disciplinary justice that linked the body of law to a body politic, and a body of space that ideologically defined and physically materialized the judicial and the extrajudicial. They demarcated that which could be represented in law, such as white landholding men, and that which was merely subject to law, such as their property, including slaves as well as potentially wives and children.23 Court buildings may have been public, but as Mabel O. Wilson comments in her “Notes on the Virginia State Capitol,” the imagination of who constituted this public was far from inclusive.24

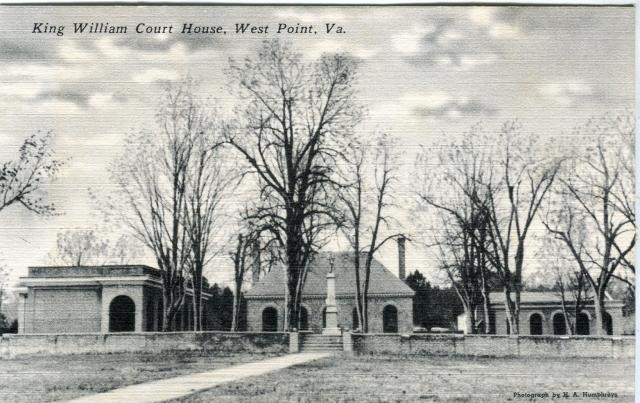

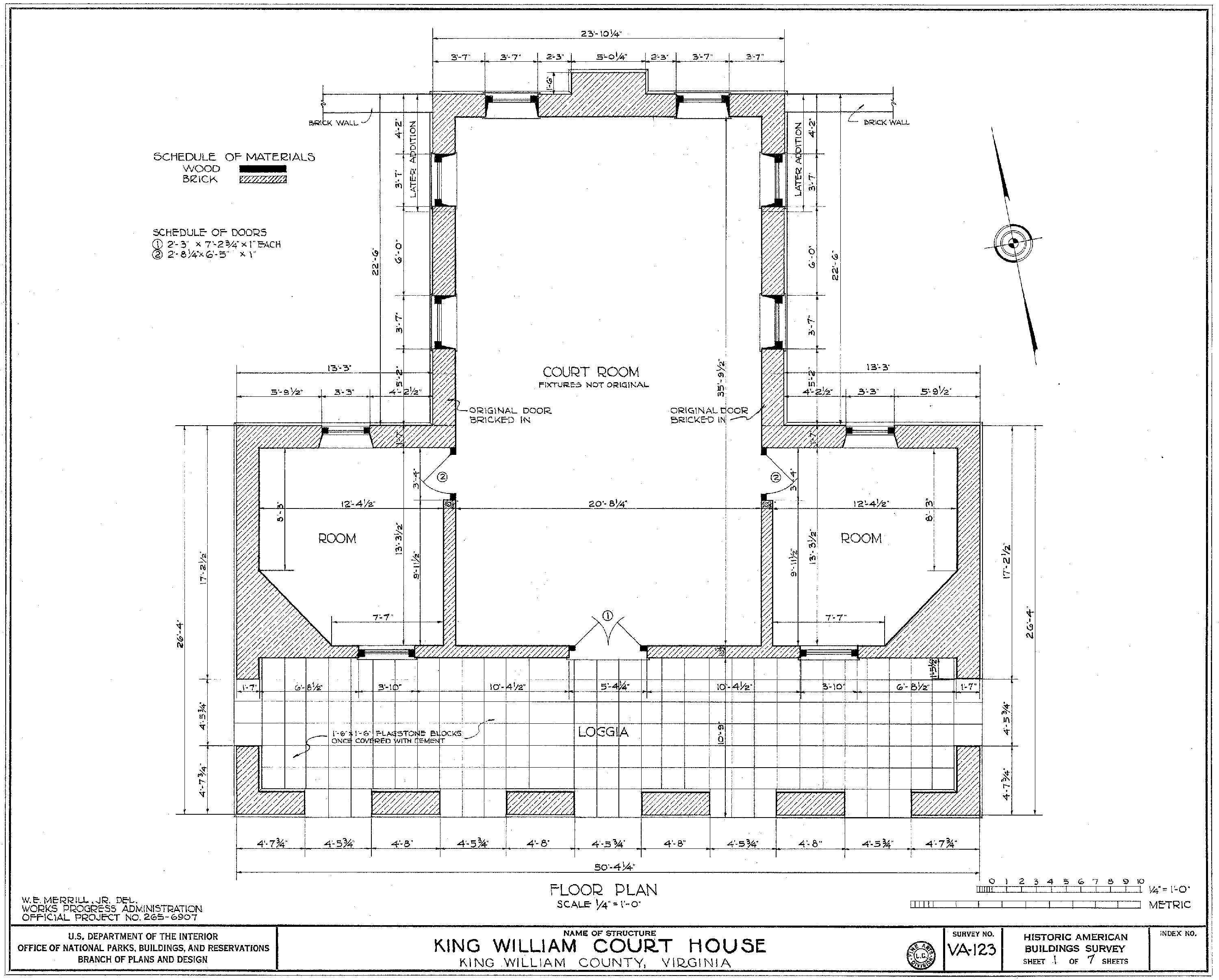

The nation’s oldest courthouse in continuous use, the King William County Courthouse in Virginia, constructed in 1725, materialized this enclosure and exclusivity.25 The building was given a brick perimeter, ensuring that unwelcome bystanders, disgruntled litigants, and more comically, nearby livestock, did not inadvertently wander into the building or interrupt proceedings.26 Preventing interruptions and ensuring order became an important driver for the interior and exterior design of courthouses throughout the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Courts provided a venue to define the principles and prove the necessary efficacy of emergent professions and institutions that promised to simultaneously organize public space and the body politic, as well as to formalize the architectural symbolism of governance. As lawyers drew on knowledge of English common law adapted to the American Colonial context for legitimacy, architects used classical Greek, Roman, and Anglican congregational styles, with their allusions to European humanism, to signify foundational principles of western civilization and present models for study, imitation, and the improvement of taste.

Both the interior spatial organization of the courtroom and the relationship of the courthouse to a territory over which it was given jurisdiction were structured such that, though “the authority of the law might be contested by a litigant, advocate, or spectator… that contest took place in space formally organized and decorated to induce deference to the administration of justice.”27 Specific procedures for various forms of addressing the court were matched with the defining of particular spaces and symbolic structures for trial parties. The now familiar raised and paneled judges platform, witness stand, jury box, lawyers’ table, and audience benches mixed earlier English courtroom precedents with elements of American ecclesiastical architecture and the increasingly distinct professional and political roles of lawyers and judges. Ancillary spaces within the courthouse, such as judges’ chambers, clerks’ offices, and meeting rooms in the nearby lawyers’ offices, were set aside for the storage and consultation of records and for conferences in which legal strategies or agreements were negotiated. These served to both ensure confidentiality and reinforce the role lawyers played in shaping access to justice. The courthouse separated public space from the space of the law, and the ritualization of actions within it naturalized and delineated the court and its participants as superordinate to everyday life while positioning the court as one of the physical, administrative, and symbolic centers of life.28

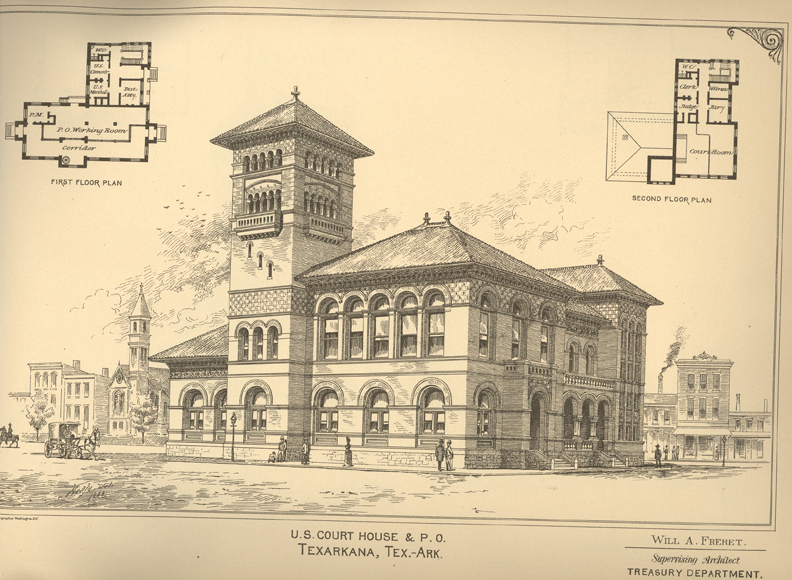

The growing density of towns on the eastern seaboard and the expansion of American territorial control further west corresponded with the formulation of an urban typology. The courthouse was frequently located on a raised plinth in the physical center of new towns, either with major roads aligned to the principal axis of the building, or else forming the boundaries of a larger courthouse square precinct, which perceptually organized the experience of the town and often the surrounding county. During westward expansion, the nascent American government transformed expropriated land into national territory by linking the American federalist imaginary to neoclassical buildings in an attempt to intellectually cultivate the nation’s growing settler population. 29 Thomas Jefferson advocated for expanding the land base of the “agrarian republic.” He also believed that neoclassical civic architecture would assist in realizing the ideals of European humanism and landed pastoralism.30 By the Reconstruction era, the majority of the many new federal courthouses being built adopted the monumental neoclassicism Jefferson had advocated. This stylistic consistency suggested both the commonality and endurance of an exclusively imagined social group—a white-settler and landed public—meant to be addressed and represented by this architecture. The rationalization and abstraction of the neoclassical style that accompanied the bureaucratization and expansion of federal administrative power amid the Progressivist and technocratic political movements of the 1910s and 1920s set the stage for the widespread adoption of a generic architectural modernism during the boom of federal court construction that followed the Depression and World War II. 31 As such, even as federal court architecture shed its neoclassical styling and was made to signify the new centers of social and political authority within industrial capitalism during the postwar period, it nonetheless retained a symbolic morphology that embodied both old exclusionary social values and legal structures as well as new forms of economic and environmental racism.

Jump to 1973.32 With financial support from The Ford Foundation, a joint committee of the AIA and the American Bar Association (ABA) on the Design of Courtrooms and Court Facilities developed a set of design guidelines for the construction of mid-century and future courthouses at state, county, and federal levels. Not coincidentally, this reappraisal of the courthouse typology followed an era of profound activism that frequently targeted courthouses as sites for demanding equal protection under the law. Titled The American Courthouse: Planning and Design for the Judicial Process, the report based its recommendations on a survey of existing court buildings (largely modeled on the typology solidified in the early nineteenth century), which carried over the physical and symbolic organizations of space that had historically privileged wealthy white settlers.33 Yet, as stated in its preface, the report was not intended to interrogate the systemic exclusions and inequalities embodied in the spaces of the judicial system:

It is not the purpose of this book to detail the existing administrative crisis in our courts today, nor to philosophize on the subject of Justice with its political and social ramifications. Public and professional pressures are being brought to bear to deal with the former; the latter is an ever-changing concept. Our goal is to establish criteria to improve the physical environment in which the judicial process occurs, based upon established functions and emerging trends. Even as recommendations are being made and implemented to expedite existing backlogs of litigation, new types of cases are proliferating, among them consumer claims, environmental class actions and civil rights cases. The pressure on our courts is not likely to ease. The demands for adjudication resulting from an ever-expanding population and new techniques for modernization of the system of court management will require appropriate facilities.34

Here, as was the case with discussions of prison design approximately forty years later, architecture and the design process were understood as fundamentally apolitical spatial “problems.” The report’s proposals prioritized issues of efficiency and security while also acknowledging the importance of symbolism to ensure continued public legitimacy of judicial power at all scales of government. Courts were to function but not necessarily to appear like “the modern office buildings” that they were beginning to resemble in the early postwar period.35 Throughout the report, race is entirely unmentioned, except in an aside about alternate methods of space allocation based on the relationship of caseload to jurisdiction demographics, raising a question about the author’s seeming assumptions regarding correlations between race and criminality or litigiousness.36

If the goal of the report was simply to develop solutions to midcentury spatial problems, the subsequent changes to both the spaces and procedures of the American legal system had decidedly political ramifications in the accessibility, transparency, and partiality of courts and their activities. Two distinct trajectories emerged. In one, legal proceedings became increasingly bureaucratic and focused on settling cases, motions, or disputed facts in private office-based pretrial conferences or discovery proceedings. In the other trajectory, cases that did go to trial were subject to performative displays of enclosure such as metal detectors and baroque spatial layouts separating accused, accuser, and public observers. Whereas the former surreptitiously removed the proceedings from public view—and thus from public accessibility and accountability—the latter, in its abundance of caution, undermined the presumptions of equality or innocence through its differential and spectacular application of physical, digital, and procedural security techniques.37 These spatial techniques also had ideologically charged procedural consequences: judges were required to counter potential bias by reminding jurors of a defendant’s presumed innocence despite potentially already appearing in prison jumpsuits, shackled, and either escorted by police from holding cells or teleconferencing from jail.38 Further, alongside an increasing pressure for pretrial settlements, the courtroom and court building have been seen by legal and psychological professionals as taking on an intimidating or terrorizing aspect, embodying “what disputants are told to fear and to avoid.”39 The issues of accessibility, transparency, and partiality raised by these trajectories have distinct racial and class dimensions that continue the exclusionary legacies of early American court spaces and jurisprudence.

Since the 1973 joint committee of the AIA and ABA, court building design has often emphasized the operation of courts as modern offices despite the report’s insistence on the necessity of their symbolic function.40 In today’s state and federal court buildings, the majority of civil and criminal cases are rarely argued in courtrooms but rather are settled in pretrial meetings that take place in private offices or via submission of written arguments and testimony to judges and clerks, not juries.41 The loss of diverse perspectives, for example, that occurs in the move from juries to judges, who are themselves facing mounting workloads, means that what little avenue for overcoming exclusionary biases may exist in being judged by one’s peers is drastically reduced. A 2018 report published by the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL) found that the increasing frequency of pretrial settlements—which they refer to as an effect of “the trial penalty”—results in longer sentences and contributes to mass incarceration, especially for people of color and the poor.42 Scholars of legal theory and critical criminology have also found that the move from the courtroom to the office and from jury to judge critically disadvantages people of color.43 The so-called public space of the courthouse is increasingly located behind the closed door of the office.

In/Justice Beyond the Gatekeeper

It is precisely this increasing separation of the spaces of the law from spaces of everyday life in the design of courtrooms, court buildings, and now pretrial spaces, that calls into question the recent focus within architectural discourse on the prison as a primary site of in/justice, anti-blackness, and design agency. This lack of attention to court buildings and court spaces in current architectural discourse is all the more startling given the fact that extensive efforts continue to be made within architectural practice to symbolically reinvigorate court building design through overly performative gestures such as the Project for Public Space’s 2009 Reinventing the Courthouse initiative or the federal Government Services Administration’s (GSA) 1994 Design Excellence Program.44 The latter program alone has given rise to dozens of federal court buildings, with many designed by prominent architects including the Wayne L. Morse US Courthouse built by Morphosis Architects in Eugene, Oregon; the Alfonse M. D’Amato US Courthouse by Richard Meier in Central Islip, New York; and the Mark O. Hatfield Courthouse by Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates in Portland, Oregon.45 These court buildings, alongside the accompanying 250-page US Courts Design Guide, have, in effect, naturalized the office-based administration of justice by limiting architectural considerations to the areas of superficial aesthetics and space planning. Even as it repudiates the GSA Design Excellence Program, the executive order signed by President Trump in December 2020 mandating the use of “classical architecture” furthers the curtailment of architectural intervention to the area of visual beauty while also whitewashing the historical and symbolic connections of this classicism with racism in the United States.46 As such, these seemingly mundane spaces in which justice and the law are supposedly brought together to determine the futures of lives and communities—spaces in which a great deal of the injustice of the American criminal justice system occurs—are the very spaces that should demand the attention of architects and designers today. Rather than beginning with the prison as a site of architectural and design intervention, an attention to court spaces reframes the prison as not the prime site but a significant symptom of antecedent yet ongoing systemic injustices based in practices of enclosure and exclusion within the American legal system since its very creation.

The exceptional case of the Central Park Five, for example, reveals the ways in which the American justice system regularly fails its citizens along lines of race, gender, and class even when defendants make it into the courtroom. The case shows the extraordinary consequence of pretrial spaces and actions in structuring the adjudication process. The false confessions coerced out of Kevin Richardson, Antron McCray, Yusef Salaam, Raymond Santana Jr., and Kharey Wise by the New York Police Department—although swiftly recanted—outweighed all the other exonerating evidence partly due to the space and conditions in which they were elicited and processed.47 Put bluntly, the ethical and amelioratory ambitions of the “good prison” and the “non-prison prison” are hollow when they house those whose standing, competency, and equality before the law has already been denied; no level of ethical consideration, no amount of green space or rooftop views, and regardless of an emphasis on topology over topography, could remedy the injustice experienced by the falsely and mass imprisoned.

To focus solely on prisons is to abdicate responsibility for real structural change and material betterment by giving in to a conservative and timid incrementalism as the AIA’s belated decision to reform its Code of Ethics attests. The editorial revisionism by which the AIA centered attention on itself and minimized its five-year delay in taking action, even misidentifying the original amendment sponsor, ADPSR, in its press releases, reflects an endemic failure by the institutions and leaders of architectural practice and education to do more than appropriate the ideas of others in a reactionary manner or to creatively imagine future practices of inclusion and recognition or Black empowerment. It is this lack of critical and creative imagination that many students, faculty, and practitioners have identified as one of the key components perpetuating anti-blackness in architecture.48 The architectural profession must now address endemic anti-blackness while also coming to terms with the profession’s contradictions: on the one hand its reliance on power and finance, and on the other its pretensions to autonomy as a discipline. How will the AIA and individual architects imagine their relationship with the incoming Biden administration and its promises to promote policies of racial justice if these policies place the well-being of broadly imagined social groups and vulnerable populations over the role of the construction sector as a catalyst for creating architecture jobs or professional prestige? Will we prove ourselves capable of the critical and creative imagination demanded to enact a more just future?

This critical imagination will necessarily have to go beyond the cliché and more permanently occupied avatars of architectural anti-blackness such as the prison, segregated suburbs, urban renewal, and gentrifying neighborhoods to engage all aspects of the built environment. Without being contradictory then, a focus on court buildings is also insufficient as they are merely another point along the pipeline of environmental in/justice. As the broad language of Gehry’s non-prison prison studios demonstrates, the designing of in/justice begins well before encountering the criminal justice system. It begins with access to education, fair housing, financial opportunity, and urban amenities. More generally, it begins with the design of the built environment. To not go beyond the most visible elements of injustice—to target only the symptoms and not the disease—implies that the discipline of architecture is more interested in the appearance of progress through rehabilitating its own image and the image of the prison, and to a lesser degree the courthouse, rather than sincerely addressing the means and ways in which architecture and design play important roles in systems of in/justice. Giving attention to the design of court buildings is one initial step in beginning to broaden the areas of design agency through which architecture and architects can further reckon with their proximity to and engagement with anti-blackness.

-

Wendy Sawyer and Peter Wagner, “Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2020,” Prison Policy Initiative, March 24, 2020 link. ↩

-

Sawyer and Wagner, “Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2020.” ↩

-

In this essay we maintain a distinction between “Black” when used to refer to people and culture, and “blackness,” when referring to an ontological position. This is because while we agree that it is important to call out the non-natural social creation of the racial designation “Black,” we also want to catholicize (anti-)blackness as an oppressive mode of thinking that affects other minoritized positions beyond Black people, especially in terms of gender, sexuality, and class. For more on debates regarding the capitalization of “Black,” see Kwame Anthony Appiah, “The Case for Capitalizing the B in Black, The Atlantic, June, 18, 2020, link. For more on calls for the discipline of architecture to confront its anti-blackness, see, for example, Amina Blacksher, et al., “Unlearning Whiteness,” Columbia GSAPP Black Faculty, July 1, 2020, link. ↩

-

ADPSR was careful to avoid impugning particular architects, firms, or buildings and instead drew attention to the reciprocal relationship between architecture, the financialization of punishment, and the blending of juridical and carceral power. Further, ADPSR’s appeal to the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights could itself be seen as a well-meaning attempt to distance American architecture from America’s particular racial biases. The colorblindness and abstraction resulting from the appeal of universal human rights veils specific material, social, and economic inequalities such as the vast racial disparity within the American criminal justice system. For more on the history of ADPSR’s petition see: Raphael Sperry, “Death by Design: An Execution Chamber at San Quentin State Prison,” Avery Review 2 (2014), link; “AIA Code of Ethics Reform,” ADPSR, link; “AIA Board of Directors Commits to Advancing Justice Through Design,” AIA, December 11, 2020, link. ↩

-

Former AIA president Helene Combs Dreiling, as quoted in an article by Michael Kimmelman, having said this at the time of the AIA’s initial rejection of ADPSR’s petition. Michael Kimmelman, “There’s No Reason for an Architect to Design a Death Chamber,” New York Times, June 15, 2020, link; “AIA Code of Ethics Reform,” link. ↩

-

Emphasis added. Kimmelman, “There’s No Reason for an Architect to Design a Death Chamber.” ↩

-

Sahil Kapur, “Trump Says He’ll Spend More than $500 Billion on Infrastructure,” Bloomberg, August 2, 2016, link. ↩

-

“AIA Pledges to Work with Donald Trump, Membership Recoils,” The Architects Newspaper, November 11, 2016, link. ↩

-

In recent years, political theorists have put forth the theory of Trumpism as a style of conservative neo-national governance and populism. Central to this theory is recognizing that Trump is a symptom of a broader and ongoing mechanism within American politics tied to continued beliefs of widespread white disenfranchisement, nativism, anti-establishmentism, post-truth, and the cult of celebrity/messianism. For more on “Trumpism,” see Cas Mudde, “Chapter 25: Trumpism,” in The Far Right in America (London: Routledge, 2017), 88–93; David Lebow, “Trumpism and the Dialectic of Neoliberal Reason,” Perspectives on Politics 17, no. 2 (June 2019): 380–398; Laura Finley and Matthew Johnson, eds., Trumpism: The Politics of Gender in a Post-Propitious America (Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publisher, 2018). ↩

-

Even within this broad imagination, there is an inherent tension that the AIA and ADPSR are attempting to navigate. This tension is formed by a professional commitment to both an individualism that conceals systemic issues on the one hand and on the other to an abstraction of identity that is so broad that it leads to a colorblindness; Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: The New Press, 2012). ↩

-

Bill Keller, “Reimagining Prison with Frank Gehry,” The New Yorker, December 21, 2017, link. ↩

-

Frank Gehry first taught his prison studio at SCI-Arc as an elective vertical studio under the title The Future of Prison. The following academic year, Gehry brought a variation of this studio to YSOA as an elective advanced design studio. The Future of Prison: Frank Gehry and Gehry Partners Advanced Design Studio, directed by Reza Monahan (2017; Los Angeles, CA: SCI-Arc Channel, 2017), digital video, link; “1101a: Design and Visualization Advanced Design Studio: Frank Gehry,” Yale School of Architecture, link. ↩

-

Treating mass incarceration as a design problem rather than as a broader social problem consequently forecloses both many means for addressing the architectures of mass incarceration in a systematic way and also reinforces a false sense that design is autonomous from the problems of politics and society; Malcolm Rio and Aaron Tobey, “That Is Not Architecture, This Is Not Urban Planning: Designing Disciplinary Obsolescence,” Frank News, May 31, 2018, link. ↩

-

A notable feature of SCI-Arc’s 2017 promotional video, The Future of Prison, is the blatant presence of the apparatus of documentary production itself. Both the number of recording devices captured in the background and the frequency with which these devices appear reflect an attention to the performative nature of Gehry’s studios and promotional media. For more criticism on these promotional videos, see: Gabrielle Printz, “Good Prison, a World Premiere,” Avery Review 37, October 18, 2018, link; Monahan, The Future of Prison; Paul Clemence, “Documentary Film Explores How Architects Can Help Reform the Criminal Justice System,” Metropolis, June 19, 2019, link; “Designing the Future,” Impact/Justice, link. ↩

-

It is important to note that the following academic year, YSOA attempted to further incorporate issues of structural injustice into its Core III sequence. However, both the studio’s final review and its retrospective publication scarcely mentioned issues of race or structural racism. Rather, the studio approached the topic of restorative justice abstractly and broadly, likely to accommodate the sequence’s main objective of designing a medium-scale building that integrates formal elements such as composition, mass, and form. Like the advanced studio run by Gehry, this focus on issues of the criminal justice system and systemic inequality as well as the partnerships between YSOA and various nonprofits, activists, and advocates did not continue the following academic year. In the wake of the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests and the many letters drafted by students to numerous deans of prominent schools of architecture, this academic year has seen a re-emergence of studios focused on issues of racial and economic injustice including a potential returned focus on the prison. We acknowledge that courses like these are occurring more frequently but seemingly only in the wake of critical breaking points in public consciousness rather than through their adoption as structural elements of curricula. It is also important to question who is teaching these studios and why, as many renowned architectural programs have frozen new hires due to the COVID-19 pandemic, tasking professors once uninterested and disengaged with issues of anti-blackness as now champions for these issues within their academy (see studios and seminars such as “Designing Social Equality: The Politics of Matter” at YSOA or “Urban Design Studio—The Power of Design and the Design of Power: Equitable Urban Typologies Challenge” at MIT). “Spaces for Restorative Justice,” Yale School of Architecture, link; Emily Abruzzo, Jennifer Trone, and AJ Artemel, Spaces for Restorative Justice (New Haven: Yale University, 2019); “1021a: Design and Visualization, Architectural Design 3,” Yale School of Architecture, 2020, link. ↩

-

That the design “solutions” put forth by students emphasized passive reformative strategies, such as education centers, worker training facilities, fair housing, and forms of community engagement should not be surprising as American housing, education, and economic development policies as well as American architecture have always been inextricably linked to systemic racism, the criminal justice system, and carceral politics. ↩

-

Monahan, The Future of Prison. ↩

-

Emphasis added. While this final statement was meant to encourage and embolden students, faculty critics, and ultimately the viewers of SCI-Arc’s promotional video, we take issue with the ways in which it forecloses other avenues of redress. The final word on the studio flattens architectural agency to solely design rather than critical self-reflection or professional reorganization and activism; Monahan, The Future of Prison. ↩

-

Exclusivity along the lines of race, gender, and class is rendered in the figure of the courthouse as parties find themselves in reciprocal relationships of legitimation with the court through processes of territorialization. French geographer Jean Gottmann explains how such processes of territorialization are linked to the ways different professions co-construct both territory and their own social positions relative to one another, especially in the areas of politics, war, geography, and the law. For more on the ways in which territory is imagined by different professions, see Jean Gottmann, The Significance of Territory (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1973), ix. ↩

-

In the US, as in Europe, the connection between courts, capital, citizenship, and politics was established early on. However, unlike many European cultures where courts were often integrated with market spaces and only later became independent buildings, courts in the United States had always been structures distinct from other public establishments; often merely repurposed domestic spaces of a landed wealthy individual; Norman W. Spaulding, “The Enclosure of Justice: Courthouse Architecture, Due Process, and the Dead Metaphor of Trial,” Yale Journal of Law and the Humanities 24, no. 1 (January 2012): 323. ↩

-

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (New York: Vintage Books, 1977), 149–152. ↩

-

For more on the history of women and the law, including coverture, feme covert, and feme sole, see Marylynn Salmon, Women and the Law of Property in Early America (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1986). ↩

-

Mabel O. Wilson, “Notes on the Virginia State Capitol: Nation, Race, and Slavery in Jefferson’s America,” Race and Modern Architecture, ed. Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis, and Mabel O. Wilson (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020), 30. ↩

-

For a listing of early county courthouses in America and a study of their typologies, see Edward T. Price, “The Central Courthouse Square in the American County Seat,” Geographical Review 58, no. 1 (January, 1968): 37–38. ↩

-

“050-0038: King William County Court House,” Virginia Department of Historic Resources, link. ↩

-

Spaulding, The Enclosure of Justice, 324, 329. ↩

-

We take the superordinate space of the court as a space in which the irrational is made rational through the application of law and the performance of magisterial rites that symbolize a distinguished difference between law and justice. The latter is understood to be subject to the whims of particular moments or influences and therefore not subject to control or suitable for the basis of government. The law as abstract body is distinguished and placed above these whims and influences in order to create the conditions for control and governance. ↩

-

In this section of the article, we do not address the style of county or state courthouses due to current limits in available archival material. A similar analysis of such courthouses would prove productive in extending these arguments to finer resolutions of territory and constituency. ↩

-

Wilson, “Notes on the Virginia State Capitol,” 23. ↩

-

For a brief period at the close of the nineteenth century, neoclassicism was supplanted by regional variations that connected architectural style with the climates and constituencies of new territories. These variations legitimized federal authority while offering a superficial image of difference. Yet with the growing role of the federal government in the face of expanding corporate power and Progressivist political movements, such stylistic variation was short-lived even as the symbolic and morphological principles such as monumentality, axiality/order, prominence, and sumptuousness that had been adapted from neoclassicism endured. This claim is based on interpreting photographic records of federal courts constructed during the twentieth century. One of the most notable shifts, that of scale, sees the typology of the house that had been the model for courts up to this time giving way to that of the office building. For a sampling of these records organized by state, see Historic Federal Courthouses, The Federal Judicial Center, link. ↩

-

This temporal jump is common in the historiography of American courthouse design in part because the structure of American jurisprudence and the organization of court spaces remained relatively static throughout much of the period between the beginning of the Civil War and World War II. As noted by Resnick, “these visual embodiments of the importance of adjudication support a conclusion that, during the twentieth century, adjudication “triumphed”; it became a form of decision making identified as key to successful market-based economies and as a requirement of politically legitimate democracies.” Judith Resnik and Dennis E. Curtis, “Representing Justice: From Renaissance Iconography to Twenty-First-Century Courthouses,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 151, no. 2 (2007): 166. ↩

-

The report was directed by Benjamin Handler on behalf of the American Bar Association and the American Institute of Architects’ Joint Committee on the Design of Courtrooms and Court Facilities. See A. Benjamin Handler, The American Courthouse: Planning and Design for the Judicial Process (Ann Arbor: Institute of Continuing Legal Education, 1973). ↩

-

Handler, The American Courthouse, vii. ↩

-

Writing on the efficiency of existing and historic courthouses, the report states that older court buildings may be obstructive to efficient contemporary judicial, clerical, and administrative work, suggesting it would be a mistake to think modern court practices did not require modern court spaces. Nevertheless, the report also argues that courthouse architecture demands design methods that go beyond simple efficient facilities. It strongly concludes that the symbolic function of the courthouse, including notably in ensuring obedience to court commands, is of equal importance to the adequate provision of office spaces; Handler, The American Courthouse, 10. ↩

-

Assumed correlations between criminality or litigiousness could also be applied to sex and age. Handler, The American Courthouse, 304. ↩

-

Lorraine H. Tong and Shawn Reese, Federal Building, Courthouses, and Facility Security (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2019), 7–10. ↩

-

Enclosure of Justice, 339–340. ↩

-

Resnick, “Representing Justice,” 171. ↩

-

Handler, The American Courthouse, 10. ↩

-

According to a 2019 Pew Research Center report, only 2 percent of federal criminal defendants go to trial with 90 percent of defendants pleading guilty pretrial. See John Gramlich, “Only 2 Percent of Federal Criminal Defendants Go to Trial, and Most Who Do Are Found Guilty,” Pew Research Institute, June 11, 2019, link; The National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, The Trial Penalty: The Sixth Amendment Right to Trial on the Verge of Extinction and How to Save It (Washington DC: National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, 2018), 5; Erica Goode, “Stronger Hand for Judges in the ‘Bazaar’ of Plea Deals,” New York Times, March 22, 2012, link; Resnick, “Representing Justice,” 171. ↩

-

NACDL specifically states that, “The capacity of the government to process large caseloads without hearings or trials has resulted in an exponential increase in incarceration. Wreaking devastation in lives and communities, and selectively concentrated among the poor and people of color, the nation’s mass incarceration has rightly been described as “the great unappreciated civil rights issue of our time.” NACDL, The Trial Penalty, 10. ↩

-

For more on racial disparity during the pretrial process, see “Pretrial Justice Bibliography,” Pretrial Justice Institute, February 2014, link. ↩

-

The Partnership for Public Space’s initiative to transform courts into “civic destinations” shares the rhetorical framing of “place-making” and other neologisms with developmentalist agendas typically tied to gentrification. Such agendas and rhetoric are, however, also inextricable from spatialized anti-blackness as demonstrated by the intersection between the Louisville Police Department’s alleged assistance in property clearance and the killing of Breonna Taylor by Louisville Police officers; Phillip M. Bailey and Tessa Duvall, “Breonna Taylor Warrant Connected to Louisville Gentrification Plan, Lawyers Say,” Louisville Courier Journal, August 30, 2020, link; “Reinventing the Courthouse,” Project for Public Spaces, January 2, 2009, link. ↩

-

The Hatfield Courthouse in Portland was one of the prime sites of both activist agitation and draconian government aggression during the protests for racial justice that occurred in the summer of 2020. That the building was taken by both sides as a symbolic embodiment of the American criminal justice system and of political power more generally makes clear that beyond the profession of architecture courthouses are already understood as sites of contestation. ↩

-

Donald J. Trump, “Executive Order on Promoting Beautiful Federal Civic Architecture,” The White House, December 18, 2020, link. ↩

-

Benjamin Weiser, “5 Exonerated in Central Park Jogger Case Agree to Settle Suit for $40 Million,” New York Times, June 19, 2014, link. ↩

-

BSA+GSAPP, On the Futility of Listening, June 25, 2020, link; RISDArc, “The Limits of Your Recognition,” risdARC, June 19, 2020, link; AASU and AfricaGSD, Notes on Credibility, link. ↩

Malcolm Rio is a graphic and architectural designer and thinker living in New York City. He is currently a PhD student at Columbia University, where he researches the historical intersections of race, sexuality, nationhood, architecture, and urbanism.

Aaron Tobey is an architectural designer and PhD candidate at Yale University. His research focuses on the development and application of computers in architectural practice alongside transformations in socio-political geographies and organizational contexts in which architects operate.