There are certain books that ask us to be aware of what we are doing and not doing in deep ways. Keller Easterling’s books are inevitably these. An Easterling book might mention the events of the last year, but it considers along with them at least a decade of other events, facts, and reference points, all from a diverse range of locales. This is so because Easterling’s subject matter is never a specific place or set of experiences, but the formulas behind these places or experiences—formulas that enact themselves in space.

Easterling’s previous projects have unpacked the history of various spatial formulas: repetitions that include everything from the American single-family house to the free trade zone. These histories are often interspersed with design alternatives. Subtraction collected a number of these alternatives into one tactical rubric.1 Medium Design: Knowing How to Work on the World, Easterling’s most recent project, differs from previous books in that it shifts the focus from a history of our failing standardized, globalized environment to a synthetic design rubric in the midst of these processes.2 Medium Design arrives ready for the pandemic and unaware of it, at the same time.3 Significantly, it marks a fault line in the field of architecture and design broadly. **WARNING: The rest of this review will be written for a Black audience.** We are well aware that not much changed in 2020: the police were not abolished, and neither was the architecture license. What shifted, however, following sustained nationwide protests and organizing in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, is that majority white institutions felt compelled to speak to Black people and some, even, to listen to Black people. This has been especially disruptive in the field of architecture, for obvious reasons. Reading Medium Design in 2021 makes it, then, a different book than it would have been in 2020. Medium Design is, perhaps, the last intelligent globally-aware book that will be written in a way that innocently preserves the invisibility and ubiquity of whiteness. It is a book that offers concepts—such as design value and interplay—that deserve to be co-opted and remixed with the theoretical rubric of Christina Sharpe’s notion of trans* or Fred Moten’s ideas of logistics.4 It is a book that—unsurprisingly—does not seem to imagine a Black audience, but one that we can imagine ourselves into (as we do)—which, as you know, is not at all distinct to Easterling.

In the spirit of Medium Design, this review proceeds from the middle of an ongoing project. As such, it is important to note that, over the past year, Easterling has already opened her work up to a new terrain of whiteness.5 But is it possible to read Medium Design, on its own terms, as an engaged Black reader without decamping to white theory or Black theory? The political terrain of Medium Design is not organized along the left or the right. “Medium design, like pool, is indeterminate in order to be practical.” (12) Assuming a majority audience, much of Medium Design makes the case for this indeterminacy as a form of efficacy that could be deployed in the midst of complex problems. For those of us who are accustomed to being the complex problem, the book offers a different insight. We can be emboldened that all of that complex indeterminacy that we live and practice and theorize might actually be a practical design attitude and methodology: one that will only be increasingly more recognized as a mode of environment making. And so this review digs into the middle, not of a certain politic, but of a line of inquiry that has transformative potential.

For much of 2020 I kept Sun Tzu’s The Art of War by my bedside.6 I have not had a nightstand since my ex-wife moved out, so the medium-size paperback rested on the floor or a windowsill. Filled with sparse pages and high-level chapter headings such as “Attack by Fire,” the book is deceptively easy to read. In part because it works on different levels of comprehension and consciousness. The chapters cluster advice and techniques for waging war thematically, but they can be read out of order. When read before sleep, the sentences can easily slide into a dream state. “There is a season for setting fires.” When read in the morning, the sentences can be clarifying and motivating. “There are days for setting fires.”

Much of the pandemic language this past year has echoed the terminology of war: the frontline, the fight, the (lack of) ammunition, the national casualties of COVID-19—compared at first to 9/11, then to Vietnam, then finally to multiple wars combined. But it was not the rhetoric of warfare that drew me to reread Sun Tzu. It was more that I sensed a through line with my own calls to action—to fabricate face shields, to ratchet up my engagements with pro-Black activism and institutional critique, to stay informed as a citizen in an election cycle. Within these contexts of being an American, and all its converging crises, a refresher seemed timely. I felt the need to be strategic, to conserve my energy, and to heighten my potential impact at the same time. Sometimes I shared passages with collaborators, but mostly I just read and reread the book to myself—feeling my way through all its strategic paradoxes.

At its best, Medium Design reads a bit like Sun Tzu. It is calm and distant from the fray of disasters and conflicts that define our collective action or inaction in the midst of climate crises and failed globalization. Easterling’s voice tends toward the wise and poetic. Chapter headings ring out with this understated wisdom: “Things Should Not Always Work”; “Problems Can Be Assets”; “You Know More Than You Can Tell”—each tells us something deceptively simple that runs counter to almost everything we have been taught, formally or informally. The text refers to intense conflicts and dangers, but generally stays far removed from them. Published by Verso in 2021, the book adds to Easterling’s heavily-researched, wonky, but gracefully-delivered set of books on the intersection of political economy and the production of the environment. Like Extrastatecraft, Medium Design traverses ecological failures, land markets, and urban peripheries, looking for ways to multiply anything that runs counter to financialization and the consolidation of corporate power—two things Easterling consistently calls “dumb.” “Knowing how to work on the world, in Easterling’s [Art of] Medium Design, means working with stupidity, not against it.

For those of us who concern ourselves with design in the midst of infrastructure and social worlds—whether as designers or as political leaders, bureaucrats, or institutional agents—the book purposefully offers no solutions. The big idea of Medium Design is to consider what we want to change as media, rather than objects, systems, people, or isms. Medium Design purports to carve out a mode of operating within this country’s incessantly reverberating culture wars, where the terms of conflict are mapped onto viral technologies instead of battlefields. The book does not map out ideologies of good versus evil, or left versus right, but rather traces what Easterling calls “Superbugs” and their web of formulas and “dumb products.” In Easterling’s formulation, a superbug is anything that can travel quickly and widely to replicate itself (from the political speech of Donald Trump to parking lots); formulas range from zoning codes to mortgage ratings to the distances between modes of transit; and products could be a way to sell a house affected by flooding or a new kind of transit hub. Much of the book remains fairly abstract and purposefully loose—there are “Interludes” instead of case studies. The interludes take us into Senate hearings, contested political campaigns in South America, Instagram accounts for paramilitary recruitment—content familiar to readers of Easterling’s Extrastatecraft.7 But, unlike Extrastatecraft, Medium Design eschews analysis of specific forms of authority. Easterling addresses this looseness and abstraction most directly in Chapter 1, “You Know More than You Can Tell.” “[M]edia theorists and designers can join forces,” she encourages (40). Rather than synthesize a book of insider design speak with a book of insider media theory speak, Easterling has chosen to excise insider speech altogether.

This would be a good place to explain that Easterling has had an outsize impact on my own work—probably more than any living theorist in the field. This is true partly because others who would have had a significant impact—such as Leslie Lokko, founder of the new African Futures Institute—were excluded from the field’s institutions for decades. (Lokko, like Easterling, writes with a literary imagination and a cultural theoretical lens on urbanism and technology.)8

Even more than Easterling’s previous work, Medium Design explains design explicitly through social anthropological ideas and methods. Chapter 1 unfurls a lineage of thinkers who trace a body of thought on artifacts as social technology and technology as social artifacts (to oversimplify). Rather than making a distinction between objects and interactions, Easterling focuses on interplay—looser than interaction, slower. If you have read Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, you might relate interplay to the temporality of the wake. As Sharpe says: “Wakes are processes; through them we think about the dead and about our relations to them; they are rituals through which to enact grief and memory.”9 Medium Design focuses on a different register of relations between living people, things, and places. Into a book of broad questions about processes, Easterling sneaks more focused topics like land transfers, librarian activism, deconstruction of houses, and multimodal transit hubs. What sort of architectural work—theoretical or practical—might we encounter if we were to consider the intergenerational interplay of memory and grief as spatial methods?

In Medium Design we do not encounter grief as much as failure and stupidity. Whether because of modernization or financialization, processes are repeated even when the outcomes are disastrous. This repetition works like a global consensus that tends to avoid much consideration, and never has to succeed. Medium Design is more concerned with charting the drift in this failing global consensus than analyzing the consensus, itself. For example, the tendency of financial indicators to chart increasingly virtual phenomena is covered in one paragraph in Chapter 2 that summarizes the language of World Bank Reports. Just a list of words, indeed, can communicate much of the narrow consensus and how it has drifted—from “dams, bridges, cement” to “assets, equity, hedging, liquidity” (60). Rather than slogging through a history of hedging or liquidity, Easterling ruminates on economists’ hunches and inserts questions of how value can be modified directly through physical dynamics rather than markets. This is such important material. It still shocks me that Easterling has this lane to herself this deep into a century that seems to need these physical thoughts so badly.

This book slices rather quickly through the history it cites on the commodification and destruction of the environment. At a rather slim 157 pages, Medium Design does not concern itself with making arguments or explaining how we got to where we are. It presumes that we readers are all in the midst of the same slow disasters and might appreciate knowing more clearly how to do what we are doing to survive and even escape the onslaught of all that “dumb” stuff and violence. Just as Sun Tzu does not write to convince you to enlist in the army, Medium Design does not make a case for a historical narrative or a set of principles. Why would you need either when “You Know More Than You Can Tell?” (Also, doesn’t that chapter title sound like something you overheard your grandmother telling one of your aunts or uncles? Possibly, starting with, “Child…”)

The heroes of Medium Design are nameless librarians running a Tor network (Library Freedom Project), Hong Kong protestors sending Bluetooth signals, and UN-Habitat bureaucrats who draft protocols for land readjustment (PILaR). Medium Design delivers these examples, but does not unpack their source code. It is assumed that you can do that elsewhere, if you are so inclined. Medium Design is more concerned with how you might be inclined in relation to others’ inclinations—what Easterling calls “undeclared temperaments” (113). The terms of medium design are not solving problems or winning arguments, but “craftiness and calculation,” “compelling and contagious stories,” the ability to “pull off more impossible tricks” (139). When we take Medium Design seriously, it almost does not seem to matter where we start—we will hit planetary crisis and financially-enabled stupidity along the way, and we will have to deal with it.

Medium Design repeatedly addresses the planetary crises and well-financed destruction at the level of what Easterling calls “the modern mind” —a way of thinking that privileges inaction and seems both rooted in the Enlightenment and very American at the same time (12). Considering this, there is an odd omission of racial logics in the book’s catalog of superbugs and undeclared temperaments. This omission is glaring both at the level of the book’s open-ended tropes and its world of design examples. This is not to say that race as a reality is never acknowledged in the book. That would be a psychosis we could expect from the Object Oriented Ontology theorists and autonomy stars in our field, not Easterling. Rather, at the level of the book’s tropes and rhetoric, I am often left wondering how much of what Easterling terms the “modern Enlightenment mind”—a disposition that the book often coaches us to evade—might be understood in terms of whiteness. (I use the word disposition deliberately here, continuing Easterling’s use in relation to Foucault’s dispositif or apparatus [34].) There are times when the escape routes from the modern Enlightenment mind track awfully close to what W. E. B. DuBois termed the “veil” or double consciousness.10 In more contemporary and feminist terms, Easterling’s disaffection for the humanities’ concern with master-narratives could be put in productive conversation with Sylvia Wynter’s interest in the human and dysbeing, or Saidiya Hartman’s speculative approach to histories of resistance.11 The notion of the Enlightenment as a mode of mind in a closed loop also seems to resonate with Denise Ferreira da Silva’s work on a Kantian subjectivity and global idea of race.12

Medium Design, however, avoids any grappling with the ways in which modernity or the Enlightenment are founded upon white supremacy. This is unfortunate, since white supremacy might be, in the terms of Medium Design, the most successful superbug of all. This omission of the white supremacist superbug leads Medium Design to cite David Harvey (49), instead of Hartman or Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor or Lawrence Bobo, to focus primarily on capitalism and finance, and to put a good deal of blame on a surprisingly vague and homogeneous thing called the “modern mind.” Harvey’s skepticism about land deeds comes up as a footnote in Medium Design in the context of debunking an economist-designed auction scheme for Rio’s favelas. As Taylor explains in her 2019 book Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership, the real estate industry in the United States profited from racial segregation even after the official end of redlining.13 Taylor calls this set of practices predatory inclusion. Predatory inclusion involved flipping houses that were never properly renovated, falsifying documents, marketing high interest rate mortgages and much more. The financial arrangements for predatory inclusion depend upon a repetition of racial difference that naturalizes both whiteness and segregation. In the terms of Medium Design, Taylor’s argument could be referenced as an example of the loop (a closed loop of reification) and the binary. It may seem that I am quibbling about a single footnote. Of course, we know the necessity to Cite Black Women… But I dwell on this because the footnotes tell the story of what we allow to become environmental knowledge and how we understand the intersection between racialization, inclusion, and theft.

Mass incarceration is not a topic addressed in Medium Design, but the methods and terms of medium design invite us to consider incarceration as a medium that we might design away. As Easterling explains in the foreword, the “Medium” in Medium Design means middle more than media. If the looseness of medium design enables design to change things already in process, the four-hundred-year history of mass incarceration in the United States would be an obvious terrain to engage. Medium design relates to what Carla Shedd calls the “carceral continuum.” In “Supply-Side Criminomics,” Shedd replaces the familiar metaphor of school-to-prison pipeline with a more nuanced and more spatial notion of the structural organization and real-time operation of ongoing punishment processes. Her essay in the field guide for Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America invites us to look at a jail-themed playground (yes, jail-themed playground) in a Brooklyn NYCHA housing project as an instance of the ever-expanding web of police control.14 In this analysis—this ally of medium design—neighborhoods and schools are understood spatially as important mediators in one’s placement on and movement along the carceral continuum. While Medium Design heralds architectures of interdependence and entanglement as strategies to effect change, one can understand the pervasiveness of the carceral continuum through this framework, as well. That is, medium design offers a more robust way to understand the resilience and dynamism of white supremacy and mass incarceration in this country—not as an accidental legacy but as a matter of design.

Shedd closes with:

We can no longer only focus on the end result of mass incarceration. Instead, we must understand the full-scale operation of the multiple systems that seed its growth. How can our built environment disrupt, rather than exacerbate, the carceral continuum? Reconstructions should be our guide.15

Unfortunately, due to the history of architecture institutions sidelining Black subjects and authors, there are not many such guides.

What are the guides to Medium Design? The book’s lack of critical concern around whiteness leads it to cite a few unfortunate design references as examples. One awkward moment in this regard is the citation of Nicholas de Monchaux’s “Local Code: Real Estates” (2010) project as the primary example for indexing empty publicly owned lots. Other examples that have had much more impact in changing attitudes to urban space include 596 Acres in Brooklyn, founded by Paula Z. Segal, an activist attorney who created a national network of similar mapping projects. David Brown, a professor at University of Illinois at Chicago’s School of Architecture and artistic director of the 2021 Chicago Architecture Biennial, has been mapping vacant lots in Chicago since 2008. Monchaux’s project is completely fine, but the multipliers that Medium Design heralds are much more evident elsewhere.

As far as the work in Reconstructions, there is a Medium Design interlude waiting to be written on the medium of public transit through the lens of Yolande Daniels’s project on Black Los Angeles.16 Chapter 3 of Medium Design, “Smart Can Be Dumb,” critiques smart city driverless car cliches, sketching out some urban alternatives with mixed transit modes woven into an assemblage of urban uses—what Easterling calls a switch exchange (75). In this chapter and others, Medium Design contrasts the heterogeneity of the assemblage with the monoculture of automotive planning. Through micro-histories and a diagrammatic tree of case law, Daniels’s work shows how car-centric public space and public transit in Los Angeles have been shaped by bad legal precedents and racial segregation. Her work reveals that the monoculture of car space has required extensive legal transformations to urbanism in ways that cannot simply be addressed by adding a bike lane. Between Daniels’ work and Medium Design we might also read something like the trike rider cultures of Harlem and the Bronx as already participating in a mode of switch exchanges and city-making.

When I think of someone who knows how to work on the world (the penultimate potential of the medium designer), I definitely think of Amanda Williams. Her project for Reconstructions includes a patent application for a “Method to Navigating to Free Black Space.”17 It sounds kind of fantastical, until you consider that kidnappers invented a way of calling some people property (including their own children born of rape). The kidnappers created a banking system and legal structure to continue the kidnapping, sex trafficking, and rape for centuries, and they cleverly called it all farming. Once Williams makes you realize this, her patent seems feasible. She is designing the way out of a middle that never ends: from middle passage to the middle of second-class citizenship.

Medium Design calls for an architecture of interdependence and entanglement; codes for interactivity; protocols of interplay; reverse-engineering the market. In the abstract, all of this feels so necessary, poignant, and attuned to our time. It seems to echo the relational work that Black artists have been staging through art institutions across this past decade. I am thinking not only of our own work in the Black Reconstruction Collective but also of Simone Leigh’s inspiring feminist work that preceded our formation—work like “The Waiting Room,” her 2016 residency project at the New Museum. Unfortunately, the actual examples propping up Medium Design sometimes fall flat compared to the nimble wisdom of its concepts and strategies. This is to be expected (or was). While we have so much work to do within the realm of practice, it is important to theorize this falling flat, too. Let it be inscribed in the realm of what Christina Sharpe calls “dysgraphia.” Let that dysgraphia encompass not only our consciousness of abjection but the void left in others’ methodologies. Let that, too, be wake work.18

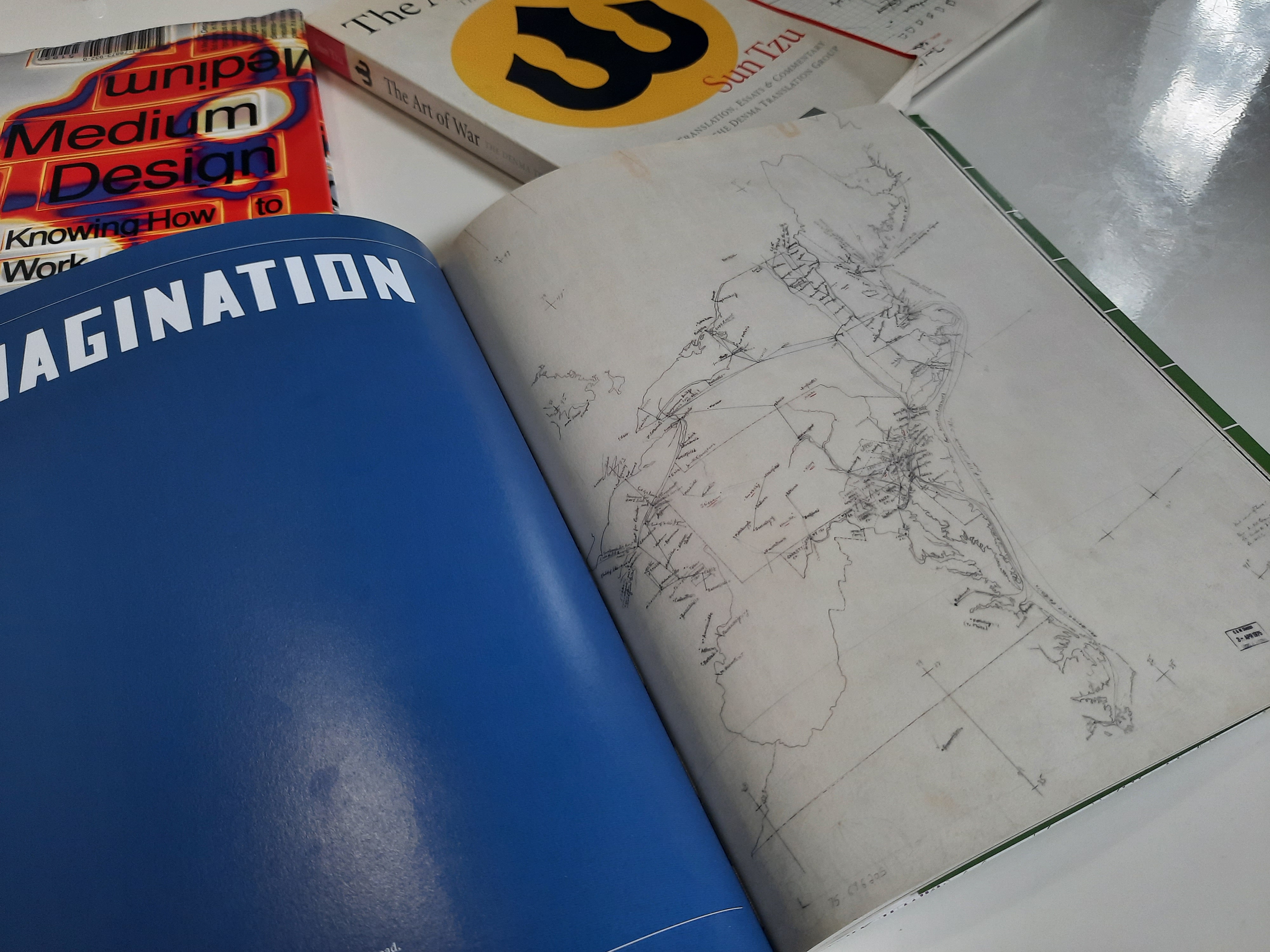

If I could close with one more pairing from the Reconstructions catalog that calls itself field guide (a guide to knowing how to work on an anti-Black world), it is the full-bleed image that opens the section “Imagination.” The credit says, simply, “Map of the Underground Railroad, 1838–60 (detail). c. 1941.” A stamp can be seen on the document that reads “APR 1975.” In this map, the northeastern part of the United States is visible, from North Carolina to Maine with the blankness of La Verendrye Canadian wildlife reserve and New Brunswick above. The lines on the map are linear enough to evoke a “railroad” only from New York to Montreal. South of New York City the map becomes a burst of lines—more akin to the diagram of a social network or a constellation of switch exchanges. It is clear that this was an architecture of interdependence and entanglement. The codes for interactivity became spatial variables. The metrics and the playbook became a way of working on the world. Yet, we have yet to acknowledge these spatial realities as victories on a battlefield called America, much less resilient design or urbanism.

Ultimately, for all its counseling against war or battle as a framework, much of Medium Design echoes one of Sun Tzu’s advices on Energy: “Indirect tactics, efficiently applied, are inexhaustible as Heaven and Earth, unending as the flow of rivers and streams; like the sun and moon, they end but to begin anew; like the four seasons, they pass away to return once more.”19 In other words, the struggle is real, and it returns. To the extent we might design in or through the struggle—not at the beginning or end but in the middle—let us recall (ancestrally, perhaps) how to be both indirect and inexhaustible.

-

Keller Easterling, Subtraction, Critical Spatial Practice 4, eds. Nikolaus Hirsch and Markus Miessen (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2014). ↩

-

Keller Easterling, Medium Design: Knowing How to Work on the World (New York: Verso, 2021). Going forward, page numbers are noted in parentheses in the main text. ↩

-

The book was written primarily in 2019. ↩

-

Christina Sharpe, “The Ship: The Trans*Atlantic,” in In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016). ↩

-

Read, for example, Easterling’s contribution to Non-Extractive Architecture: On Designing without Depletion, vol. 1, ed. Space Caviar (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2021). ↩

-

Sun Tzu, The Art of War, trans. The Denma Translation Group (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2001). ↩

-

Keller Easterling, Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space (New York: Verso, 2016). ↩

-

About a decade ago, as director and curator of the Brooklyn architecture nonprofit Superfront, I studied the html source code of Easterling’s early 2000s web-based projects and tried to archive them. While living and working in Detroit for three years my primary projects—a building called House Opera and a mapping project titled Watercraft—were in dialog with two of her books, Subtraction and Extrastatecraft, respectively. ↩

-

Sharpe, In the Wake, 21. ↩

-

W. E. B. Du Bois, “The Forethought,” in The Souls of Black Folk (New York: Penguin, 1903), vii–viii. ↩

-

Saidiya Hartman, “The Anarchy of Colored Girls Assembled in a Riotous Manner,” South Atlantic Quarterly 117, no. 3 (2018): 465–490. ↩

-

Denise Ferreira da Silva, Toward a Global Idea of Race (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007). ↩

-

Keeanga Yamahtta-Taylor, Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019). ↩

-

Carla Shedd, “Supply-Side Criminomics,” in Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America, eds. Sean Anderson and Mabel O. Wilson (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2021), 78–79. ↩

-

Shedd, “Supply-Side Criminomics,” 79. ↩

-

J. Yolande Daniels, “black city: the los angeles edition,” in Reconstructions, 148–153. ↩

-

Amanda Williams, “Directions to Black Space (After Mutabaruka) in Reconstructions, 134–145. ↩

-

Sharpe, In the Wake, 17. ↩

-

See no. 6 in “V. Energy” of Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, translated by Lionel Giles, here: link. ↩

V. Mitch McEwen is an architectural designer, urban designer, principal of Atelier Office, and one of ten co-founders of the Black Reconstruction Collective. McEwen also teaches at Princeton School of Architecture, where she directs the research group Black Box, exploring mixed human-robotic processes in design and construction. Her work has been exhibited at the Venice Biennale of Architecture, Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, Istanbul Design Biennial, Storefront for Art and Architecture, and the Museum of Modern Art.