It could happen to someone looking back over his life that he realized that almost all the deeper obligations he had endured in its course originated in people who everyone agreed had the traits of a “destructive character.” He would stumble on this fact one day, perhaps by chance, and the heavier the shock dealt to him, the better his chances of representing the destructive character.1

Architects Eric Kahn and Russell Thomsen’s proposal “Thinking the Future of Auschwitz” begins with two facts. First: An average of more than one million people visit Auschwitz I and II (Birkenau) annually. Second: Auschwitz I and II suffer from what Kahn and Thomsen refer to as an evidentiary problematic: The camps serve as historical evidence, yet their claim to authenticity is jeopardized through acts of preservation. The first fact alerts us to the immense physical stress placed on these sites; the second reveals the inherent difficulty of memorializing an event through physical remains. These two facts place Auschwitz I and II in a double bind: To endure as both a place of pilgrimage and a site of testimony, Auschwitz and Birkenau require both maintenance and rebuilding (preservation), yet the necessary modifications, additions, and subtractions betray the expectation of authenticity claimed by visitors and the demand for permanence made by memory.

The desire to turn a site of historical significance—which is always split, fractured, heterogenous, not one with itself, unstable, and contested—into a stable referent for meaning is the natural condition of all acts of memorialization. The prevailing norm governing the genre of the contemporary memorial museum is to fulfill this desire for stability (of memory and meaning) by securing an identity that is self-same (i.e., one that does not change over time). Kahn and Thomsen’s proposal questions this desire by reorienting our temporal horizon away from a logic of self-sameness toward one of difference, where memory is both an intergenerational demand and an intragenerational responsibility.

Their proposal’s strength emerges from this conceptual and material reorientation, a shift that forces us to come to terms with three related historical conditions. First, with the inevitable loss of survivors, memories of the Shoah are moving from immediate and direct experience to mediated and indirect modes of transmission and reception. The second condition concerns the physical state of the former camps. While the smaller and self-contained Auschwitz I has been preserved in the form of a museum (equipped with exhibition space, research, preservation, and curatorial staff), the much larger Birkenau (approximately 370 acres) is in an advanced state of ruin. The third condition, which challenges all site-specific acts of memorialization, has to do with the way in which one views Auschwitz as a locus of trauma. Trauma materialized in and through physical space is called upon to authenticate and thus validate one’s claim to recognition of memory, meaning, and experience. Without authenticity, so the argument goes, there would be no way of legitimizing competing political claims to memory.

From these three historical conditions, two questions emerge: What becomes of memory and meaning with the inevitable and uncontrollable diasporic proliferation of Holocaust simulacra? And how can evidence, in this instance place, remain vital without resorting to the default construction of a memorial, museum, or cemetery?

Kahn and Thomsen’s proposal responds immediately and directly to these challenges. Given the uncertain future of Auschwitz, Kahn and Thomsen foreground chance and contingency as design strategies for (and means of) architectural production. Rather than construct a univocal, stable, and coherent narrative—the norm governing sites of collective trauma—their proposal attempts to preserve its instability, prioritizing the incalculable over the known. Reframing our horizon of expectation, “Thinking the Future of Auschwitz” invites us to participate in the question of meaning as an event (as opposed to one that is prescribed). Obviating the human demand for meaning, the work cedes to nature in order to perpetuate the question of meaning.

Historical exigencies present the future of Auschwitz as a choice between restoration and ruin. “Thinking the Future of Auschwitz” rejects this choice, arguing instead for the permanent suspension of meaning through non-narrative incomprehension: to acknowledge trauma and loss without the imposition of political and ethical imperatives (i.e., survive, secure, mourn, remember, learn).2

While politicians debate sovereignty and make nationalistic claims to justify institutional proposals in the form of monuments and memorials, and while historians and cultural critics continue to add to the enormous volumes already written in an attempt to understand the Shoah, we would argue that perhaps only art is (any longer) capable of dealing with the enormity of the caesura. Art not as an answer, but true to its proper role, art that sets this place apart, that brings the spectator into a moment of crisis in which he or she must determine what he or she confronts.3

By situating their work within the discourse of art, Kahn and Thomsen refigure the evidentiary problematic of architectural preservation—beset with technical, juridical, religious, and political issues—as a provocation.4 Invoking the biblical notion of a Tel Olam, a Hebrew term suggesting something everlasting—perpetual, permanent, enduring, eternal—Kahn and Thomsen alert us to the temporal shift performed by their proposal.5

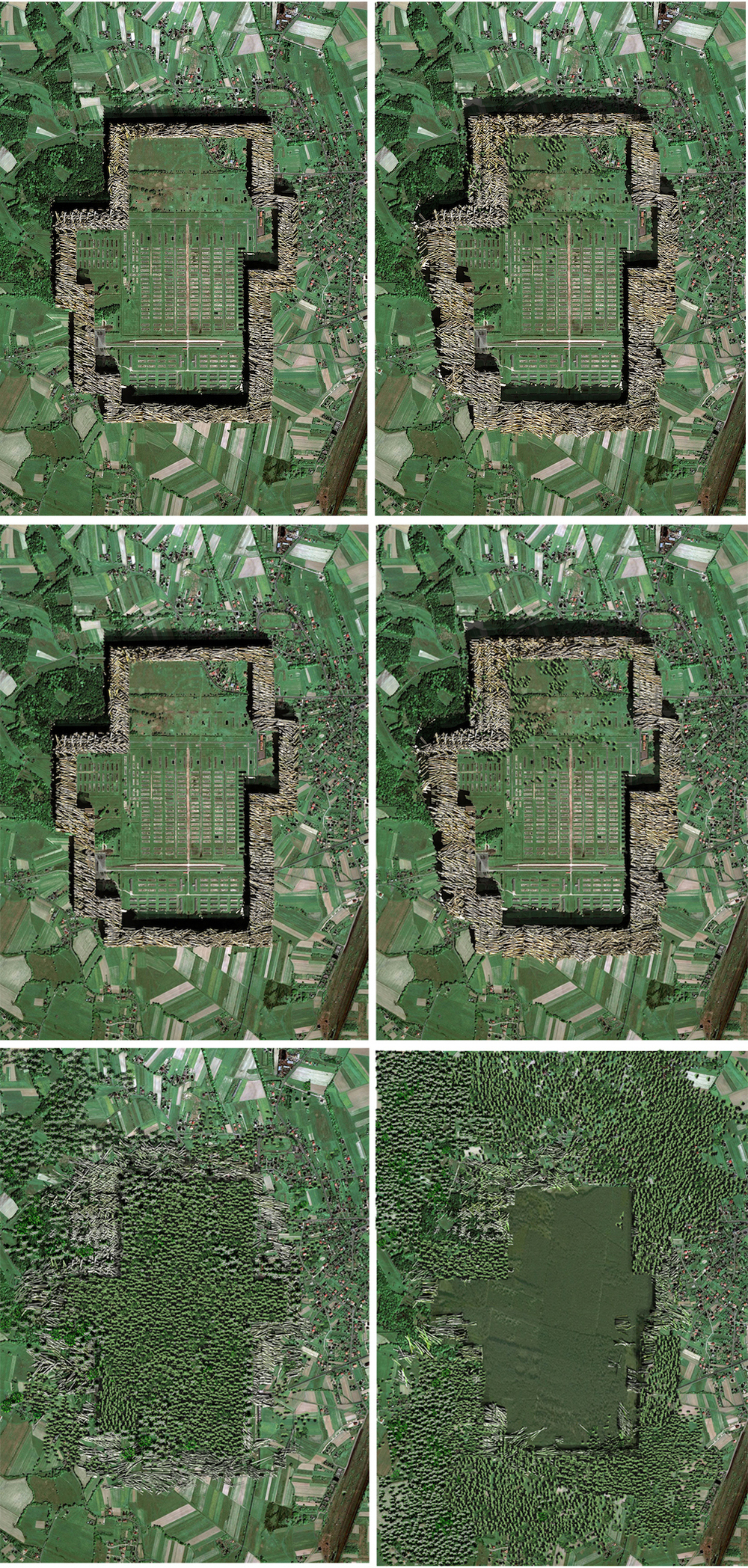

After the last survivor has passed, a Tel Olam at Birkenau is to be constructed as a procedural event. Initially set as an ordered system surrounding the camp, it will be composed of a series of stacks of tree trunks, harvested from each of the European countries where victims were deported. The trees will be stacked to form a perimeter wall approximately thirty feet high encircling the grounds and ruins of the camp, effectively separating it from the surrounding world and barring entrance from the outside. Initially the stacks will be orderly and solid, but the logic of nature as an entropic field will contribute to their inevitable ruin. A caesuric act of separation from the world, Birkenau will be ritually expelled and physically placed outside of humanity, rendering the landscape purposeless, radically opening a future for Auschwitz 6

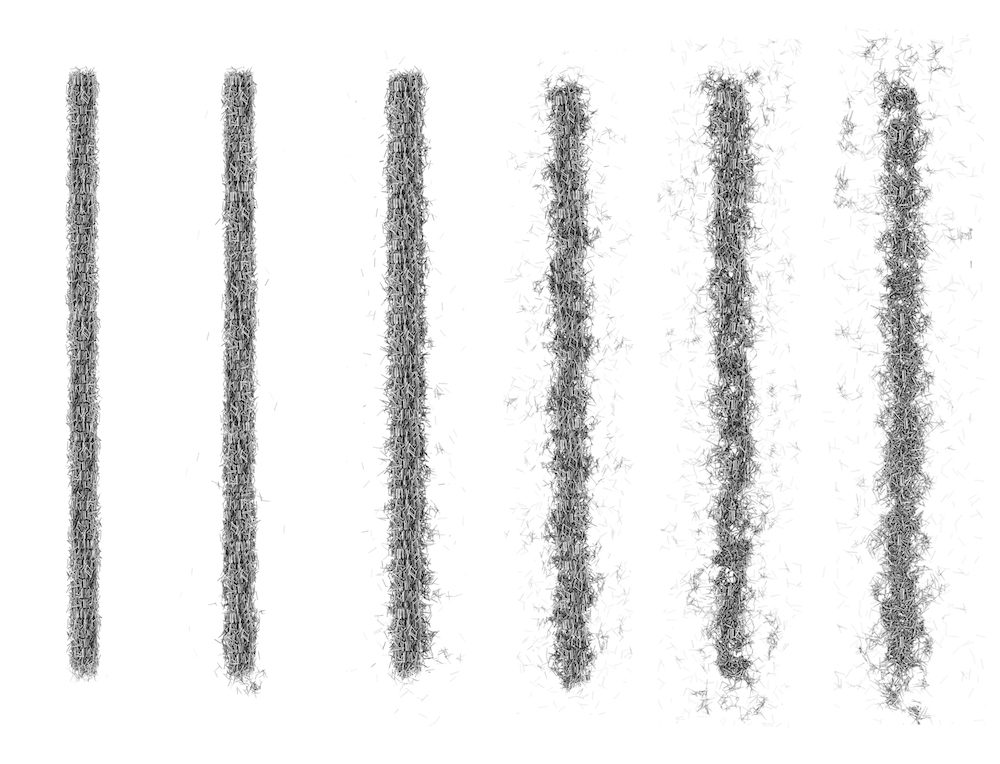

To construct one’s work as a procedural event suggests a sequential, controlled, and systematic process that invites something immediate, unexpected, and without qualification. The commingling of temporal conditions—sequential (then) and immediate (now)—suspends the binary logic of for/against and either/or. This interruption of received codes enables Kahn and Thomsen to put into play both order and entropy, solidity and ruin, indeterminacy and inevitability. Often considered to be mutually exclusive, these couplings facilitate an engagement with the past that is at once familiar (i.e., recognizable) and foreign (i.e., incalculable).

We know what it means to separate through partitioning, to distinguish an inside from an outside. We divide this from that not only to enclose but also to identify. Despite the fact that Kahn and Thomsen use a wall to enclose Birkenau, effectively transforming the site into a perpetual ruin, their proposal troubles our ability to identify inside from outside, us from them, then from now.

The destructive character sees no image hovering before him. He has few needs, and the least of them is to know what will replace what has been destroyed. First of all, for a moment at least, empty space—the place where the thing stood or the victim lived. Someone is sure to be found who needs this space without occupying it.7

What, then, are the effects—historical, psychic, aesthetic, ecological, political, economic—of withholding, of prohibiting, of excluding what Kahn and Thomsen identify as the regime of culture from the regime of nature? Both regimes articulate a logic of control governing a system of relations, values, and hierarchies. While the regime of culture reflects coherence and order (by way of signs and facts), the regime of nature reveals itself as flux. Irregular and seemingly without order, nature’s temporality is characterized by growth, passing, and decay, cycles operating outside of the referential economy of knowledge, identity, and reason.

Each regime is defined by its own temporal horizon, yet they are not opposed. Kahn and Thomsen’s proposal allows for the commingling of temporal conditions, with Auschwitz I participating in the regime of culture, fulfilling the demands and expectations of the knowledge, and Birkenau provoking a non-didactic subjective experience with the past. With Roland Barthes’ punctum and Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe’s caesura, Kahn and Thomsen’s withholding effects a break, rupture, and tear in time: “a caesuric act of separation from the world …” that is, from the world of man, reason, intention, knowledge, and, ultimately, understanding.8 9

The destructive character has no interest in being understood. Attempts in this direction he regards as superficial. Being misunderstood cannot harm him. On the contrary, he provokes it.10

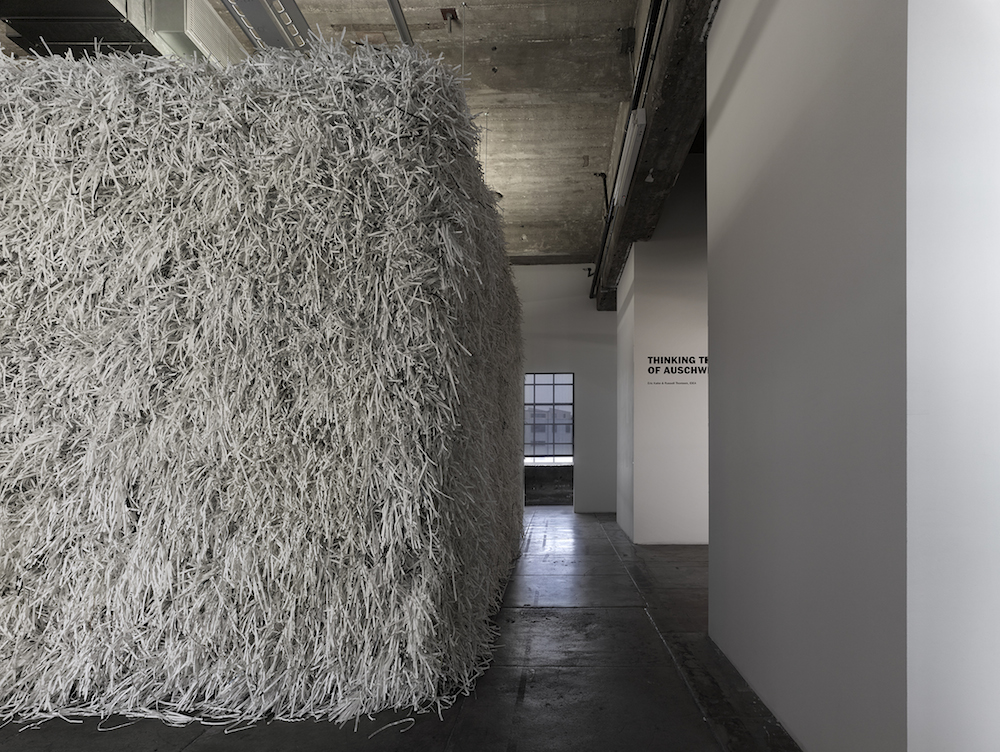

This past November Kahn and Thomsen exhibited their proposal “Thinking the Future of Auschwitz” at the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc). The exhibition featured an 8-foot wall enclosure that held an inaccessible space in the center of the school’s library. Without explanation or apology, the enclosure obstructed passage through the library while also prohibiting visitors from entering the space circumscribed within. The figure traced by the wall continually frustrated being recognized as such. Resisting totalization, the object refused to offer visitors a point of view from which they could take in and assimilate the whole. The installation’s withdrawal from participating in the regime of culture’s demand for identification communicated the cognitive opacity of Kahn and Thomsen’s proposal for Auschwitz. Walls of shredded paper not only prevented entry and occupancy but kept visitors from seeing what, if anything, was inside.

The Shoah, Kahn and Thomsen claim, defies understanding. Despite qualification and quantification, the events it signifies remain opaque and impenetrable. It is for this reason that Kahn and Thomsen foreground the role of entropy in their proposal. Entropy, they argue, forces the question of the Shoah to be asked again and again, renewing both memory and forgetting as a vital life force.11 Setting the conditions in place for the landscape to ruin, the project abandons the idea of achieving understanding through an encounter with authenticity, and instead puts forward the possibility of a contingent and perpetually inexhaustible experience with the question of meaning.

For Kahn and Thomsen, memory and meaning are renewed by the arrival of an unknown and ever-changing destination.

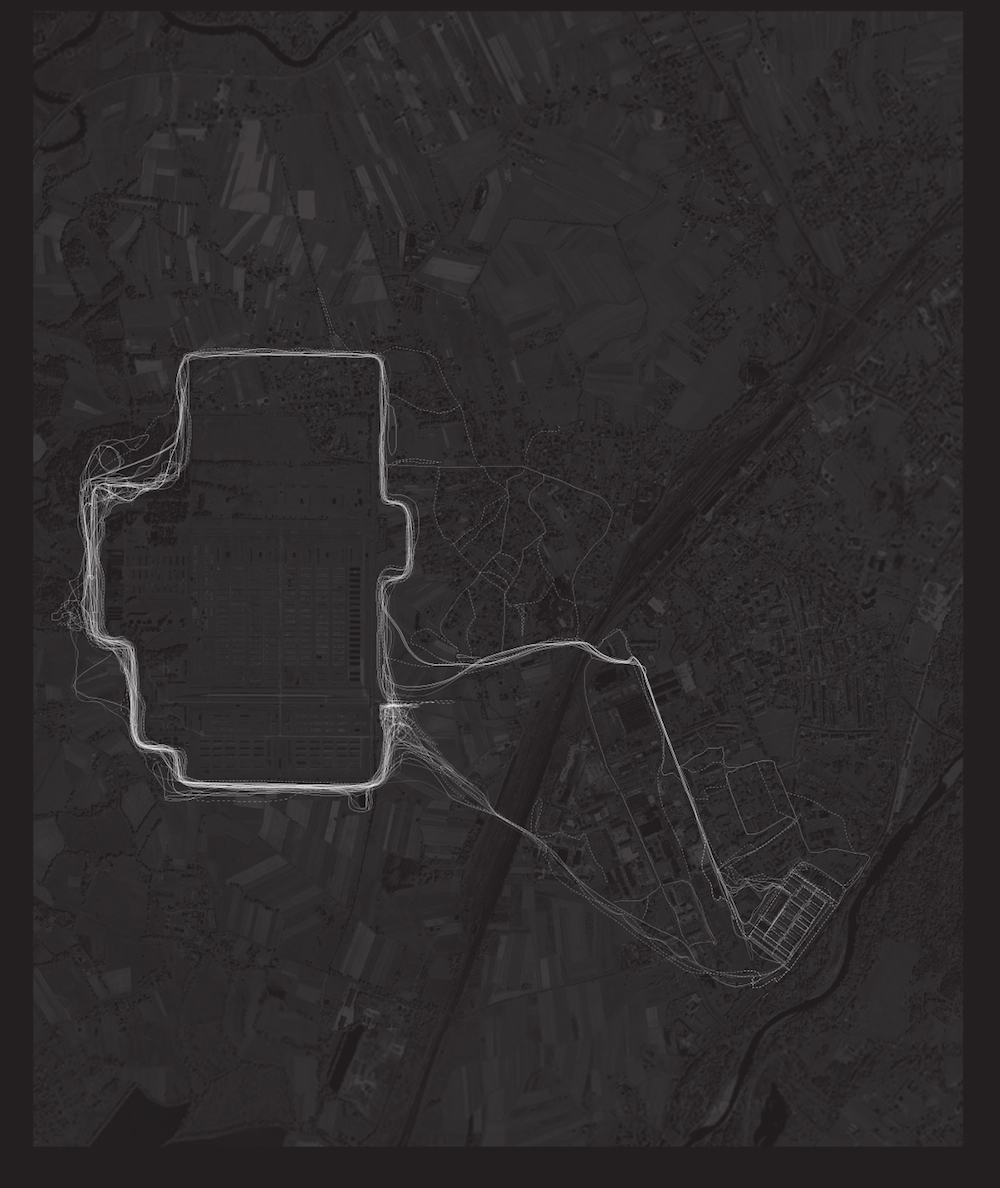

After viewing the Memorial Museum at Auschwitz I, visitors would travel to Birkenau to walk the perimeter of the Tel Olam, creating an emergent ritual that would allow for an in-absentia assertion and recording of the camp. The perimeter condition would acquire new significance, one contingent on the perpetual line that defines the inside from the outside. The various paths inscribed into the landscape by the wanderings of the vast multitudes of visitors would slowly accumulate over the years, marking a common journey without common answers. By shifting the perception of Birkenau from the time of culture to the time of nature, a new ontology for the camp emerges. The interior of the camp would express itself as a presence of absence (a blanking), a withholding that would transform how it is apprehended and would ultimately seek to manifest the ineffable, that which could not be named.12

The primacy of withholding in the work is paramount. The power of withholding comes from its ability to provoke and stimulate, to stoke desire, to perpetuate a question. Withholding reframes the question of the Shoah from What does this mean? to What does this mean for us? As the perimeter of Birkenau changes over time, so does the question, such that it can maintain itself as a question, one that acquires its significance for a particular people at a particular time.

The destructive character obliterates even the traces of destruction.13

Anxiety over access to the site and its preservation persist. In a recent article, former executive director of the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust, Mark Rothman, argued that “preserving [Auschwitz] as authentically as possible allows for those voices, those whispers of history, to continue to be heard. You don’t hear anything from nothing.”14 A similar claim was made by the former project director of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), Michael Berenbaum: “The most powerful things at Auschwitz I come from Birkenau. The things you remember, the things that send chills up and down your spine—the shoes, the hair the suitcases, [and other items]—all of this is material that was taken from Auschwitz II and brought to Auschwitz I.”15 These related perspectives betray the insatiable desire for authenticity prevalent throughout our culture of commemoration. The claim to authenticity made by historical artifacts appeals to our desire to know first-hand, to have a material witness and connection to what “actually” happened. While this desire is natural, it is not productive, for both the witness and its testimony must always be identified and interpreted to acquire significance.

Standing in the middle of a landscape of trauma, as Rothman and Berenbaum would have it, positions visitors within a continuum between what is and what has been, between the living and the dead, projecting authenticity as an objective fact realized through a visceral and tactile engagement with historical artifacts, such as those collected and exhibited by the USHMM.16 Experiencing history as such promotes a cognitive and affective relation with the past but leaves its meaning unquestioned. This is a problem, for it releases visitors from the responsibility of reconciling themselves with the past.17 Ultimately, the preoccupation with authenticity is bound to a logic of recognition, which falls back on symbolism—circulating values through self-referential codes—and thus privatizes the public and political work of judgment.

The preoccupation with authenticity that characterizes our culture of commemoration returns us to the nineteenth-century historicist’s concern with presenting the past “as it was,” that is, to offer a comprehensive and unified account through which a particular phenomenon is made legible for human experience in general. For such a historicism, the primary function of history is not to judge the past, but to display it accurately, where accuracy is measured by objectivity resulting from the accumulation of facts supported by empirically verifiable evidence. This is the role played by the collection and exhibition of shoes, hair, suitcases, and other such historical artifacts at Auschwitz I and the ambition motivating the preservation of the few material remains—namely, built structures—at Birkenau. The desire for authenticity emerges from an evidentiary crisis (of credibility and legitimacy): To be able to speak authoritatively of and for a history one claims to represent.

Some people pass things down to posterity, by making them untouchable and thus conserving them; others pass on situations, by making them practicable and thus liquidating them. The latter are called destructive.18

By returning the site to nature, Kahn and Thomsen refigure the problem of authenticity and representation as one of entropy and signification. This material and physical shift is a necessary precondition for their project’s reframing of time. “Thinking the Future of Auschwitz” illustrates the way in which memory and meaning are never one with themselves, but rather constitutively split, undergoing processes of unending change and transformation. Plastic and dynamic, memory concentrates and releases its energy when necessary, that is, when one or more individuals bring a particular fragment of the past into relation with a particular situation/problem/question/challenge in the present to open a political space outside of the logic of representation. Moving from a logic of representation to one of signification suggests that the life of meaning is always contingent, local, particular, and situated. Meaning is not given in the objective structure of events but is created in and through the political work of thinking and judging. Authenticity misses the point, for the sheer factuality of past events is not enough to guarantee their political significance. No objectivist (i.e., positivist, historicist) account of the past can possibly satisfy this condition of meaningfulness.

We learn from Walter Benjamin that to take up a work—in whatever form—one must recognize that work as having been intended for them at a particular moment in time and space. “For it is an irretrievable image of the past which threatens to disappear in any present which does not recognize itself as intimated in that image.”19 There is an urgency to recover from all that has been this image, this question, at this moment. “Thinking the Future of Auschwitz” presents us with such an urgency.

Benjamin does well to remind us that the moment of urgency can always be missed. But it is this very possibility of missing that enables meaning to live its fragile existence. Kahn and Thomsen’s “Thinking the Future of Auschwitz” is an effort to pluralize meaning and return the labor of memory back to the thinking, feeling, and judging spectator. By acknowledging the non-identity of thought and the incommensurability of meaning, Kahn and Thomsen foreground a mode of historical transmission in which the meaning of an event changes as it is received by the inheritors of a tradition who bring to it their own life experiences. Experience, both past and present, enters tradition not as a given set of inherited meanings or customs that one is bound—by tradition—to uphold, but as an ongoing practice of creating and communicating meaning about and for the past. For this past what has happened cannot be changed. What can be changed is how we relate to the past.

-

Walter Benjamin, “The Destructive Character” in Selected Writings: Volume 2: 1927-1934, ed. Howard Eiland, Michael W. Jennings, Gary Smith (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001), 541-542. Originally published in the Frankfurter Zeitung, November 20, 1931. ↩

-

“Acknowledgment goes beyond knowledge. (Goes beyond not, so to speak, in the order of knowledge, but in its requirement that to do something or reveal something on the basis of that knowledge.)” Stanley Cavell’s resignification of the term acknowledgment draws out its participatory demands. Acknowledgement is a matter of what we do with respect to our knowledge of others, of how we perceive and project our expectations of others in light of what we know. Stanley Cavell, “Knowing and Acknowledging,” in Must We Mean What We Say? A Book of Essays (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976), 257. ↩

-

Eric Kahn and Russell Thomsen, excerpt from the wall text accompanying their exhibition “Thinking the Future of Auschwitz,” SCI-Arc Library Gallery, November 3–December 5, 2014. ↩

-

It is worth citing Theodor Adorno’s often misunderstood claim about the possibility to produce art after Auschwitz in its entirety. The original quote comes from “Cultural Criticism and Society” (1949): “The more total society becomes, the greater the reification of the mind and the more paradoxical its effort to escape reification on its own. Even the most extreme consciousness of doom threatens to degenerate into idle chatter. Cultural criticism finds itself faced with the final stage of the dialectic of culture and barbarism. To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric. And this corrodes even the knowledge of why it has become impossible to write poetry today. Absolute reification, which presupposed intellectual progress as one of its elements, is now preparing to absorb the mind entirely. Critical intelligence cannot be equal to this challenge as long as it confines itself to self-satisfied contemplation.” The events signified by Auschwitz trouble the pursuit of art, insofar as they demonstrate the ability of a culture to produce works of aesthetic beauty while also committing acts of mass violence. Whether consciously, explicitly, intentionally or not, art is complicit in the barbarism of the culture in which it is produced. It is productive to read Adorno’s remarks on the dialectic of culture and barbarism alongside Walter Benjamin’s claim about culture and barbarism in “Theses on the Philosophy of History” (1940): “There is no document of civilization that is not at the same time a document of barbarism.” Thesis VII. The urgency and challenge given by both Adorno and Benjamin is to recognize and struggle to overcome the complicity with barbarism in everything we say, do, think, make, etc. One is never impartial or nonpartisan. Theodor Adorno, Prisms, trans. Samuel and Shierry Weber (Cambridge: MIT, 1998), 34; Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” in The Continental Philosophy Reader, ed. Richard Kearney and Mara Rainwater (New York: Routledge, 1996). ↩

-

“A biblical term for a place whose physical past should be blotted out forever. That is to say, the Holocaust should remain to us forever an ‘empty place,’ a place that we can never hope to possess or actually occupy.” F.R. Ankersmit, Historical Representation (Stanford: Stanford University Press), cited within the exhibition “Thinking the Future of Auschwitz,” SCI-Arc Library Gallery, November 3–December 5, 2014. ↩

-

Eric Kahn and Russell Thomsen, excerpt from the wall text accompanying their exhibition “Thinking the Future of Auschwitz,” SCI-Arc Library Gallery, November 3–December 5, 2014. ↩

-

Benjamin, “The Destructive Character.” ↩

-

Inflicting a kind of trauma on the viewer, the punctum refers to a subjective detail that challenges and changes one’s reading of a photograph. Imminent and unexpected, the punctum yields a private meaning separate and distinct from that of the culturally conditioned (coded) studium. Like the regimes of culture and nature, the studium and the punctum designate two distinct temporal modalities. Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), 25-42. ↩

-

Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe’s concept of the caesura is instructive on this point. “A caesura would be that which, within history, interrupts history and opens up another possibility of history, or else closes off all possibility of history.” The caesura refers exclusively to what Lacoue-Labarthe describes as a pure event, “an empty or null event, in which is revealed— without revealing itself— a withdrawal or nothingness.” There is a caesura where immediacy is interrupted and cut-off. If the caesura is not the concept of historicity, Lacoue-Labarthe argues, then it is at least one of its most fundamental precepts. Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, Heidegger, Art and Politics (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1990), 45. ↩

-

Benjamin, “The Destructive Character." ↩

-

Friedrich Nietzsche’s “On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life” (1874) articulates a relationship between the individual and time that is simultaneously historical and unhistorical. Nietzsche proposes active forgetting, an intentional act of letting go that affirms the past without binding it to the present. Such forgetting, what he describes as the capacity to feel unhistorically and be in the present, is a source of happiness. Active forgetting breaks with the past by remembering things selectively (and constantly revising what is being remembered), that is, by distinguishing that which is productive for life from that which inhibits it, thereby enabling individuals to act with and against, inside and outside, their particular history. “…the unhistorical and the historical are necessary in equal measure for the health of an individual, of a people and of a culture.” Friedrich Nietzsche, “On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life,” Untimely Meditations, ed., Daniel Breazeale (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 63. ↩

-

Eric Kahn and Russell Thomsen (IDEA), excerpt from a forthcoming essay in Perspecta: The Yale Architectural Journal on “Thinking the Future of Auschwitz.” As a marker of authenticity, absence materializes the temporal disjunctions of physical destruction. Symbolizing loss through emptiness, absence gives presence to the past by evoking personal memories in the subjective realm of introspective reflection. Abstract and ineffable, absence speaks the language of silence. ↩

-

Benjamin, “The Destructive Character.” ↩

-

Mike Boehm, “What To Do at Auschwitz?” Los Angeles Times, November 27, 2014, latimes.com/entertainment/arts/la-et-cm-auschwitz-memorial-idea-office-20141128-story.html. ↩

-

Ryan E. Smith, “Preserving Auschwitz?” Jewish Journal, January 30, 2013, jewishjournal.com/los_angeles/article/preserving_auschwitz. ↩

-

Educational and cultural institutions, like the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), best meet the demand of knowledge by advancing and disseminating information, preserving the memory of those who suffered and encouraging their visitors to reflect upon the moral and spiritual questions raised by the events they represent. However, institutions entrusted by the public to generate awareness and provoke understanding of historical events should also orient and enable the formation of a critical public capable of acknowledging what they know and making the kind of political judgments that are essential to democracy. We need our inroads to memory to allow for more than one-way conversations with the past. ↩

-

Reconciliation is different from understanding and identification. As Hannah Arendt explains: “The task of the mind is to understand what happened, and this understanding, according to Hegel, is man’s way of reconciling himself with reality; its actual end is to be at peace with the world.” Reconciling oneself with reality, following Arendt, is an unending activity through which we come to terms with and reconcile ourselves to the sheer givenness of the world. “Thinking the Future of Auschwitz” presents us with this challenge, of how to think without bringing reflection to an end, to speak without bringing conversation to an end, to argue without bringing disagreement to an end, to find understanding without foreclosing the question of meaning. Hannah Arendt, “Preface to Between Past and Future,” in Between Past and Future (New York: Penguin Books, 1993), 6. ↩

-

Benjamin, “The Destructive Character.” ↩

-

“Historicism presents the eternal image of the past, whereas historical materialism presents a given experience with the past—an experience that is unique. The replacement of the epic element by the constructive element proves to be the condition for this experience. The immense forces bound up in historicism’s ‘Once upon a time’ are liberated in this experience.” Walter Benjamin, “Edward Fuchs, Collector and Historian,” in The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility and Other Writings on Media (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2008), 116-119. ↩

Jake Matatyaou is the principal of the research and design practice June and a faculty member at the Southern California Institute of Architecture in Los Angeles.