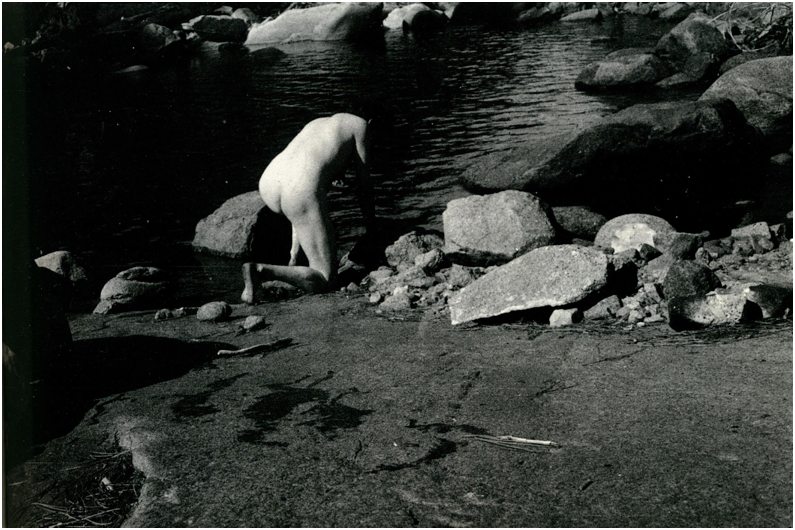

In 1921, the Viennese émigré architect Rudolf Michael Schindler and his newlywed wife Pauline Gibling honeymooned in Yosemite National Park. They set up camp in a grove of tall trees, their little tent dappled by sunlight. There is a snapshot from this trip: captured by Pauline, Schindler is preparing to bathe in a placid cove. Nude, he kneels by the rocks on the water’s edge, unaware of his wife’s gaze. The soles of his feet are caked in dirt, and his back, legs, and buttocks are warmed by the sun. In this tableau, the architect is Diana and his wife is Actaeon.1 The reversal of the forbidden, erotic gaze, crystallized in this mythic scene, anticipates the complexity and dangers of desire.

The two began their married life on a plot of land on Kings Road in the shadow of the Hollywood Hills, a stone’s throw from Irving Gill’s Dodge House, and quickly immersed themselves in the cultural life of Southern California. Their home soon became a gathering place for members of the artistic, political, and intellectual avant-garde. The guest list was extensive: Upton Sinclair, Edward Weston, Aldous Huxley, Anaïs Nin, Theodore Dreiser, Katherine Dunham, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Igor Stravinsky, Galka Scheyer, and Louise and Walter Arensburg. The Schindlers moved in with another young couple, the Chaces, who each had creative ambitions of their own. The house’s pinwheel design was composed of four studios and a guest suite—each of the inhabitants, whether they were man or woman, husband or wife, would be granted the space to cultivate their own creative pursuits and enjoy the privileges of both solitude and community. There is an undeniable romance to the whole endeavor—something charming about the Schindlers’ youthful idealism. They imagined the house to be a “cooperative dwelling,” one that would choreograph social relations in concrete and wood, making material the desire to be at once within and outside of ourselves.2 Flattening social hierarchies while embracing the natural world, the house dissolves the material and psychic boundaries between interior and exterior, public and private. From the bare concrete walls and exposed redwood beams to the sliding panel doors and built-in furniture, Schindler envisioned an architecture that would fade quietly into the background of the inhabitants’ bohemian, collective lives.

As a home for two newlyweds, the Schindler House proposes an alternative to the heteronormative spatialization of domesticity and sexuality that defines the nuclear family. Instead of creating rooms for specialized purposes, the activities of everyday life—eating, working, playing, sleeping—are dispersed throughout the house and grounds.3 One of the architect’s more radical experiments was the creation of semi-enclosed sleeping baskets perched atop the house. While these sleeping arrangements were soon abandoned for the warmth and cover of the indoor studios, the basket frames remain. By designing what were essentially open-air bedrooms, the private and sanctified act of procreation between husband and wife is quite literally out in the open. If we consider the historical conception of heterosexual marriage as a form of domestication and procreation as a way to reproduce social order, then the prototypical family home is an active and recurring mechanism of control.

In 2016, the artists Brennan Gerard and Ryan Kelly, working together as Gerard & Kelly, embarked on a project called Modern Living to examine what they call “livability of a queer space—its pleasures, tensions, and impossibilities.”4 Through a series of live performances and dance films written and choreographed for the camera, Gerard & Kelly use shared principles of dance and architecture—form, rhythm, circulation, proximity—to multiply the sensual possibilities latent in modernism. Each of the canonical houses they engage—the Schindler House, Phillip Johnson’s Glass House, Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House, and Eileen Gray’s villa E-1027—are attempts to liberate the modern subject by abstracting the spatial configuration of the home. Each of their inhabitants led lives that were unconventional for their time. While Johnson and Gray were openly gay and bisexual, respectively, it is not just the architects’ identities that mark these spaces as “queer” but the way in which desire is encoded and performed in architectural space that imbues them with radical potentiality. Furthermore, each of these homes is marked by their own set of idiosyncrasies and contradictions. The Glass House, for example, was designed as a home for Johnson and his partner, David Whitney, but the couple never intended to sleep there. Instead, Johnson conceived of a separate, opaque building that would house their bedroom. Plinth-like in its severity, the Brick House is an architectural foil to its glass neighbor. The interior bedroom is framed by a series of arches and swathed in fabric, a veritable chamber of sensual pleasure: “This was a bedroom, why not get cuddly?” Johnson said.5

The Schindler House presents a contradiction of a different sort. Pauline’s reputation as a leftist, freethinking woman and her instrumental role in preserving her home’s legacy is widely acknowledged, and there are scandalous tales surrounding the parties and events she would host: in 1928, the dancers John Bovingdon and Jeanya Marling opened a “dance studio-laboratory” at the Schindler House and caused quite a stir when nude and nearly nude dancers were seen cavorting in the sunken garden by the neighbors.6 And yet, despite the abundance of narratives about the house’s radical programming, Pauline still had her personal prejudices: “But as free as the atmosphere [of the house] was, the rules of conduct were no different from those imposed by any Bloomsbury hostess. Pauline’s criticism of a guest with bad manners was that he ‘was not a thoroughbred.’”7 Around 1948, Kenneth Anger and Curtis Harrington screened their experimental films Fireworks and Fragment of Seeking on Kings Road. John Cage—with whom Pauline had a brief affair in the 1930s—was there with his future partner, Merce Cunningham. Confronted with explicit scenes of queer life and fantasy, Pauline’s limits were reached—she called the two filmmakers a week later and accused them both of being “very sick young men.”8 It is unlikely that they were invited for subsequent screenings or events.

Gerard & Kelly’s two-channel film, Schindler/Glass, completed in 2017 and exhibited this summer at Pioneer Works in Brooklyn, begins in New Canaan and slowly fades into Los Angeles. The dancers perform intimacy and desire in a multitude of forms, ranging from what could be a warm, affectionate relationship between sisters to an intensely erotic liaison between two men. At New Canaan, the dancers take full advantage of the multitude of vantage points afforded by the main house’s translucent walls and accentuate the spatial relationship between the three structures on the grounds. A pair of dancers weave in and out of the concrete arches of the outdoor pavilion, while a third walks around the bed inside the Glass House. Alongside original music by Lucky Dragons and SOPHIE, there are the sounds of birds and the steady, pulsating calls from the dancers, “1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3, 4, 4, 4, 4…” Their voices float in and out of the main house, where a young woman lies nude on Mies van der Rohe’s black Barcelona daybed. She whispers intimate memories of past rendezvous, the kind that you repeat to yourself while lying in bed at night, alone: “Your sheets were softer than mine…Seeing your silhouette in the shower…your sweat dripping onto me…”

Framed by the door of the Brick House, a pair of male dancers perform a fierce pas de deux. In classical ballet, the pas de deux is choreographed courtship, usually between two principal dancers of the opposite sex: an approach, flirtation, and consummation of love. Gerard & Kelly’s first pas de deux at the Glass House is steady and rhythmic—as a shirtless man watches from the bed, the two dancers use each other’s bodies as weight and counterweight. Their bodies snap in and out of place, each gesture a coded sign. One man pushes the other away repeatedly until he finally pushes too hard, too far. It is a tense engagement, made more ominous by the dancers repeating the phrase, “relationships like clockwork, clockwork…”

There is a repressive quality to the first half of the film in New Canaan—an air of melancholy pervades the grounds. The last scene inside the Glass House happens at sunset. A group of dancers, dressed uniformly in sexy black suits, march in place, swinging their arms like that of a ticking clock. The architect’s personal life—his transparent homosexuality and early flirtation with fascism—colors the scene. Susan Sontag put it best: “[fascism’s] choreography alternates between ceaseless motion and a congealed, static, ‘virile’ posing.”9 Gerard & Kelly evoke the unsavory truths that mar Johnson’s legacy by appropriating fascism’s dark glamour, seducing the viewer with repressed sexual energy and stylized violence. Johnson’s architectural eroticism is present only as temptation—the glass walls of his house simultaneously reveal and occlude his desires. Two decades after Pauline chastised Kenneth Anger for being “a sick young man,” Anger created the experimental short film Scorpio Rising that features leather-clad motorcycle riders, Nazi paraphernalia, and Jesus Christ. Again, to Sontag: “The color is black, the material is leather, the seduction is beauty, the justification is honesty, the aim is ecstasy, the fantasy is death.”10

But now, back to Los Angeles, where a fire is burning brightly inside the Schindler House, warming the concrete walls and casting soft shadows. A female dancer in front of the fireplace begins to perform a series of gestures that are seen and copied by another dancer in the next room. A chain of movement is created: the original gesture is interpreted by a network of dancers inside, outside, and on top of the house. This opening sequence can be read as an homage to the late choreographer Trisha Brown, whose Roof Piece first took place in Lower Manhattan in 1971 and was restaged by the High Line in 2011. With choreographic gestures transmitted through bodies, walls, and windows, the sequence highlights the literal and metaphorical porosity of Schindler’s architecture as well as the way in which the house “unfolds logically and inevitably.”11

Interiority in the house is tenuous and fleeting—rather than gazing inward, both the original inhabitants and the dancers are directed to look through the house’s abundant windows and to the world outside. Schindler’s tilt-slab technique means that single slabs of concrete separate interior and exterior, turning solid walls into thin membranes that gently enclose space. The seams between the slabs are expressed by thin, vertical slits that, viewed from the inside, transform into columns of pure light. The house’s material permeability is also reflective of Schindler’s view on modern living. In an essay titled “Furniture and the Modern House: A Theory of Interior Design,” he writes,

Our time, with a more democratic scheme, has discovered the meaning of the neighbor and allows us to stretch our hands horizontally. It has accorded to any individual the privilege of the king to consider himself and his action sacred at all times. Our houses lose their forbidding faces and become three-dimensional beings in a three-dimensional world.12

For the architect, the “forbidding faces” and layered domestic spaces of the past were the architectural manifestation of a desire to insulate and protect ourselves from the untold dangers of the outside world. The modern house instead must shed its heavy walls, small windows, and dim light in order to embrace “the earth, the sky, and the neighbor.”13 The neighbor is a recurring figure in Schindler’s writing, mentioned alongside elements of the natural world. This vision is profoundly ecological: like the southern California sun or desert breeze, the neighbor is a constant presence that does not live with us but besides us. As both a metaphor for existing in the world and a discrete subject of identification, the neighbor encompasses a wide range of relational possibilities that exceed the binary.14 In relational terms, the neighbor is the social and spatial interlocutor between stranger and kin.

At the Schindler House today, there is a lush bamboo grove that forms a porous but definitive boundary against the two upscale condominium complexes that are its immediate neighbors. One of these is Habitat 825, a nineteen-unit project completed in 2007 that consists of two “L”-shaped blocks that interlock and bow slightly inward to create a central courtyard. In a gesture of neighborliness, the block directly adjacent to the Schindler House is single story so as to not cast unwelcome shadows. The architects write, “Attempting to ‘kick down the bamboo wall,’ Habitat 825 and its expansive use of common open space creates an urban space without borders or property lines.”15 They have also planned for a future integration of the two sites: the central courtyard is projected to extend beyond the “bamboo wall” and directly into the eastern side of the Schindler House.

Looking at photographs of the Schindler House in the 1920s, the landscape of West Hollywood is dominated by dusty shrubbery and the Hollywood Hills in the distance. This part of town had not yet been incorporated into Los Angeles County and consisted mostly of farmland, dotted with small developments north of Wilshire Boulevard. With the financial help of Pauline’s parents, Schindler bought the half-acre parcel of land directly from Walter Dodge, who was actively developing the “newest of the high-class foothill subdivisions.”16 Schindler must have built the house knowing that the neighborhood would increase in density, but there is a sense of irony in the character of the house’s new neighbors. Habitat 825 capitalizes upon the house’s status as an iconic landmark while corrupting Schindler’s romantic idea of modern, communal living—their stated desire to “kick down the bamboo wall” is a violent assertion of dominance that undermines any form of neighborly goodwill. Rather than dissolve “borders or property lines” for the sake of hospitality, Habitat 825’s encroachment onto the Schindler House’s grounds is a thinly veiled effort to consume the site’s cultural significance for the sake of financial gain. It is unsurprising that the MAK Center for Art and Architecture, the institution that oversees the Schindler House, was strongly opposed to the entire project from the beginning.17

Unlike the choreography at the Glass House, the dancers in Los Angeles showcase the Schindler House in its ideal, romanticized form. There is barely a visual mention of neighbors encroaching on the property, nor is there the sense of impending violence. Rather than suppressing intimacy and erotic desire, the dancers give in, letting it rise to the surface and boil over under the warmth of the California sun. Within the film, the house functions less as proscenium stage and more like a subtle series of frames for the choreography. There are no clear establishing shots to provide a sense of the house’s size or overall relation between building and grounds. The house is also devoid of furniture, emphasizing the relation between the body and architectural space: rather than sitting on chairs, the dancers place their bodies directly on the concrete floor. Windows, doorways, and even slits in the house’s walls are utilized as viewing mechanisms—a complex choreography of gazes is constructed as the dancers dance together and apart, woven together by sightlines. Their bodies are framed by and, in some ways, constrained by the house with its low concrete, wood-beamed ceiling. Duets that begin inside the house move outside into the lush patio and gardens.

After a duet that begins inside the house, two women move outside into the lush patio and gardens. They sit in the garden as they undo and touch each other’s hair while singing Allen Ginsburg’s poem Gospel Nobel Truths in perfect harmony: Look when you look / Hear what you hear / Taste what you taste here / Smell what you smell / Touch what you touch. Meanwhile, the tragic pas de deux that began at the Glass House is revisited and this time, concludes with a joyful leap into the patio’s sunken garden. It is an undeniably sensual viewing experience, and not just because we see flesh: throughout the choreography, the materiality of the body and the surface of skin is experienced audibly through rhythmic slaps. There are gentle caresses, frantic touches, and longing looks, but what is more striking is the way that intimacy expands beyond two individuals: pas de deux become pas de trois, pas de quatre... As two dancing pairs trade partners over and over, they recite, “the just distribution of two men and two women…two and two…two and two…” They thrust their hips back and forth until they let go of each other and let their bodies spasm.

There is an oppressive, ceaseless rhythm to normative heterosexual relationships: two people in love must love in sync. Modern love is epitomized in companionate marriage: like the narrative in a pas de deux, you meet, date, consummate. Kiss, stroke, penetrate, climax (together ideally). Repeat as necessary. Relationships like clockwork, clockwork.18 The last sequence of the film disrupts this rhythm and choreographs an alternative. On one channel, four dancers—two men and two women—walk briskly around each other on the patio. They are soon joined by other dancers, and the group grows larger. The incessant beat of a snare drum plays in the background, heightening the tension as the dancers weave in and out of one another, ever cognizant of each other’s movement and speed. In the second channel, the dancers are huddled together—repeatedly whispering into each other’s ears: “The family is a system of regeneration…” Suddenly, they gasp and collapse to the ground. The last scene of the film is a close-up shot of all the dancers piled together on the grass, their bodies gently writhing; “the goal of queer space is orgasm…it lasts for a moment, but during that moment, you give yourself over to pure pleasure made flesh.”19

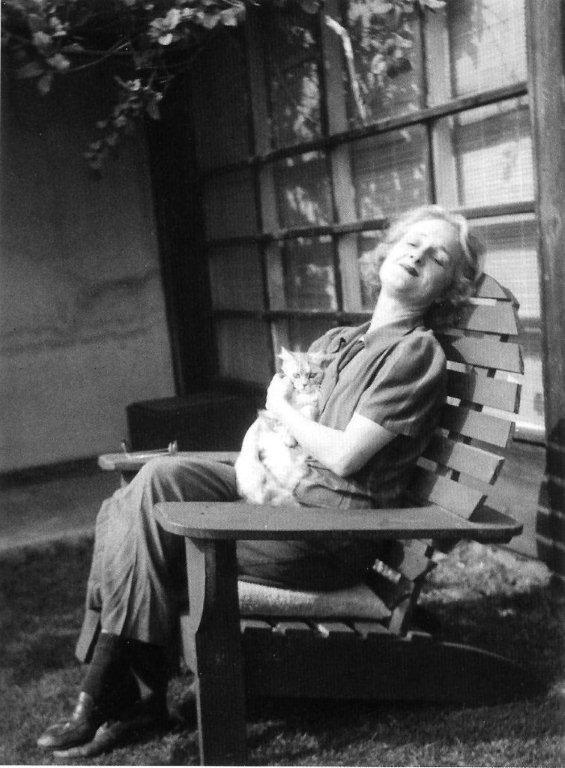

The dancers move in the same way that Pauline characterized her relationship with Schindler: together but apart, “one and divisible.”20 After leaving Schindler to join various utopian and artistic communities in California, she returned to the house almost a decade later in 1938 and continued to live there with him for the next four decades. She occupied one side of the house while he the other. They communicated through letters passed through a mail slot between two rooms: he addressed her as Madam; she called him Mr. Schindler.21 Collective living takes on a new form in the house’s later years—while it was conceived of as a home for two married couples, it evolved into one that could accommodate a man and woman living platonically, side by side. After Schindler died in 1953, Pauline continued to live on Kings Road and worked diligently to preserve her partner’s legacy. She was a highly sociable and charismatic woman and it was often observed that while Schindler was the house’s architect, she was its hostess. She has become so inextricably tied to the house’s history that Reyner Banham wrote in 1979, two years after her death,

While the house is rightly remembered as a locus of the historical avant-garde as well as a modernist masterpiece, stories about it often include gossip about its inhabitants’ sex lives: Schindler is rumored to have been quite promiscuous, and Pauline’s affair with John Cage never goes unmentioned.22 These tales worked to reinforce the house’s reputation as a sensual site of liberation, where one could nurture individual and collective life in equal measure. In a letter that Pauline wrote to her mother in 1916, she professes, “One of my dreams, Mother, is to have, some day, a little joy of a bungalow, on the edge of the woods and mountains near a crowded city, which shall be open just as some people’s hearts are open, to friends of all classes and types.” Pauline’s sentiment, so pure and sincere, was ultimately impeded by the day-to-day realities of domestic life: marriages, friendships, and professional associations began to fracture soon after they moved in.23 And despite living a life that directly challenge dominant arrangements of marriage and sexuality, her admonishment of Anger and Harrington reveals the limits of her vision.

The Schindler House’s legacy is tinged by a nostalgia for the future—the anxiety toward our own present, combined with the difficulty of producing a new model for living and loving, pushes us to look for answers in the unfulfilled promises of modernism.24 Gerard & Kelly’s choreographic and filmic interventions offer fleeting visions of queer life within these now canonical sites. Rather than attempting to directly redress the various shortcomings of Schindler’s experiment in modern living, we see the appropriation of its architecture as a site for pure, unadulterated pleasure, which even today, is a radical act. As the dancers’ bodies converge and depart beyond the walls of the house, we experience the possibility of loving together, out of sync.

-

Diana and Actaeon are two figures from Greek and Roman mythology. The story is recounted in Ovid’s Metamorphoses: Diana (known to the Greeks as Artemis) is the virgin goddess of the hunt. Actaeon is a young hunter who one day, while out with his hounds, stumbles upon the goddess and her escorts bathing in a cove. As the escorts attempt to quickly cover Diana’s nude body, she becomes enraged by the young man’s unwitting transgression and transforms him into a deer. Tragically, Actaeon is killed by his own hounds, who fail to recognize their owner. In addition to being the subject of numerous paintings, the story was adapted into a ballet that premiered in 1868 by the Imperial Russian Ballet. Since then, the parts of Actaeon and Diana have been danced as a pas de deux most famously by Anna Pavlova and Vaslav Nijinsky. George Balanchine danced the part of the Satyr in 1917. I would like to thank Amanda Ju for pointing me to this reading of the photograph. ↩

-

R. M. Schindler, “A Cooperative Dwelling,” T Square 2, February (1932): 20–21. ↩

-

During the house’s construction process, both Pauline and Marian Chace became pregnant. Realizing that the plans for the house did not include a nursery, Schindler was forced to create a makeshift space located between two studios in which to house the newborns. ↩

-

“Modern Living,” Projects, Gerard & Kelly, link. Modern Living is an ongoing series of live performances and films that began in 2016: in addition to Schindler/Glass, there have been live performances at the Schindler House, the Glass House, the Farnsworth House, and Pioneer Works in Brooklyn. Their new film, Farnsworth/Gray, took place at the Farnsworth House and E-1027. ↩

-

Quoted from interview conducted on behalf of the National Trust for Historic Preservation by Eleanor Devens, Franz Schultz, Jeffrey Shaw, and Frank Sanchis. See “Brick House, Overview,” The Glass House, link. For a queer reading of the Glass House and the Brick House, see Aaron Betsky, Queer Space (New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1997), 114–16. ↩

-

Esther McCoy, Vienna to Los Angeles (Santa Monica, CA: Arts + Architecture Press, 1979), 59. ↩

-

McCoy, Vienna to Los Angeles, 40. ↩

-

Ara Osterweil, “America Year Zero: Ara Osterweil on Kenneth Anger’s Fireworks,” Artforum, January 2017. ↩

-

Susan Sontag, “Fascinating Fascism,” the New York Review of Books, February 6, 1975. ↩

-

Susan Sontag, “Fascinating Fascism.” ↩

-

Robert Sweeney, “Life at Kings Road: as it was, 1920–1940,” The Architecture of R. M. Schindler (New York: Abrams Books, 2001), 59. ↩

-

R. M. Schindler, “Furniture and the Modern House: A Theory of Interior Design” in Furniture of R. M. Schindler (Seattle: University of Washington Press), 50. ↩

-

R. M. Schindler, “Care of the Body,” the Los Angeles Times, May 2, 1926. ↩

-

Here, I am directly invoking Eve Kosofky Sedgwick’s theorization of the term “beside”—she writes, “Beside permits a spacious agnosticism about several of the linear logics that enforce dualistic thinking: noncontradiction or the law of the excluded middle, cause versus effect, subject versus object. Its interest does not, however, depend on a fantasy of metonymically egalitarian or even pacific relations, as any child knows who’s shared a bed with siblings. Beside comprises a wide range of desiring, identifying, representing, repelling, paralleling, differentiating, rivaling, leaning, twisting, mimicking, withdrawing, attracting, aggressing, warping, and other relations.” From Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2003). ↩

-

“Habitat 825/Lorcan O’Herlihy Architects,” ArchDaily, April 20, 2009, link. ↩

-

Thomas S. Hines, Irving Gill and the Architecture of Reform (New York: Monacelli Press) 231–2. ↩

-

“Habitat 825: Lorcan O’Herlihy Architects,” Architect Magazine, May 31, 2013, link. ↩

-

Elizabeth Freeman has written on the queer temporality of Gerard & Kelly’s You Call This Progress? (2010), Reusable Parts/Endless Love (2011), and Kiss Solo (2012). See Elizabeth Freeman, “Timing sex in the age of digital reproduction: Gerard & Kelly’s Kisses,” New Formations 92, (2017): 25–40. ↩

-

Betsy, Queer Space, 17. ↩

-

McCoy, Vienna to Los Angeles, 59. ↩

-

McCoy, Vienna to Los Angeles, 59.

Unrecognizable in its ambuscade of exotic trees and shrubs, [the house] has now become a southern California legend. I have known it since 1965 but have only recently had the good fortune to live in it, and found it as delicious, delicate, and comfortable as appearances had always promised. But haunted; echoing with a ghostly absence. Pauline doesn’t live there anymore. She was no woman of the home in any ordinary sense of the word, for she was nothing ordinary, ever.[^22]

-

Letters between John Cage and Pauline Schindler, who was twenty years his senior, were published in ex tempore, vol. 8, no.1, (Summer 1996) and is available through East of Borneo’s website, link. ↩

-

After the Chaces abruptly moved out, Richard Neutra, his wife, and their young son joined the Schindlers. Neutra and R. M. Schindler commenced a bitter rivalry despite once being close friends and professional partners. ↩

-

The phrase “nostalgia for the future” arose out of a conversation between Rhea Anastas, Gregg Bordowitz, Andrea Fraser, Jutta Koether, and Glenn Ligon, “The Artist Is a Currency,” Grey Room vol. 24, no. The Status of the Subject (Summer 2006): 110–125. ↩

Mimi Cheng is a PhD student in the Visual and Cultural Studies program at the University of Rochester, where she works on global histories of modern architecture and architectural theory.