Some (rare) books are so adept at skipping between styles or fusing varied conceptual approaches that you start to forget how rigid and formulaic most texts—academic or otherwise—really are. Beatriz Preciado’s Pornotopia is a remarkable instance of what becomes possible when you disregard the confines of a genre and instead speak to the problem at hand. The “problem” here is the Playboy empire, a sprawling, multimedia, multi-format cultural institution that characterizes the sexual, psychic, and social imaginary of America after the 1950s. Except that for Preciado, the language of “characterization,” of cultural impressions, tired and superficial ways of expressing influence and significance are swept aside by an entirely deeper and more convincing frame: We are not talking (again) about vague symbolic influence, or Cold War “ideologies” but about architecture physically controlling and constructing “technohabits”; this is less a theory about “subjectivities” than it is an account of the total immersion of bodies under what Preciado calls the “pharmacopornographic regime.” “If you want to change a man, change his apartment,” Preciado writes. “If you want to modify gender, transform architecture.” The playboy apartment, the “pad,” with all its connotations of an animal virility taken indoors “stripped down the house walls, producing a totally naked (but over-coded) domesticity: the interior space as sexualized topos,” 1 Preciado tells us. The architecture of the Playboy universe materially manufactures the new, modern male. It is this boldness of vision, Preciado’s willingness to go beyond the usual platitudes, however comforting, that really marks this book out. It is thus a vision of a vision: not merely an account “of” but a replication of a force field into which you have already been sucked, whether or not you noticed it.

Like Preciado’s earlier Testo Junkie, this book not only changes what you think, but the embodied, libidinal, and hormonal way in which you relate to how you think it. You will never quite be the same again after reading Pornotopia, simply because the world was not the same after Playboy, and all the facts that tumble from this revelation have little to do with whether you are interested in Playboy or not. I personally had very little interest in Playboy, nor, indeed, did Preciado before s/he began this project (“Being a transgender and queer activist…I do not need to confess that Playboy had not been a part of my private library before”). 2 But something about this libidinal, political, and cultural distance seems to have created in Preciado’s work a new “view from nowhere” as a critical approach: not the flat indifference of a bored critic, but the marvel and wonder of discovering an entirely new object and being able to explain it as if for the first time: Preciado grabs the Playboy empire by the neck and seizes, in particular, on the image of an insomniac Hugh Hefner, high on amphetamines, editing his magazine from his revolving bed. This image then becomes a kind of crystal through and out of which the entirety of the late twentieth century is refracted.

There is nothing naïve about Preciado’s take, nor moralistic either (though certainly Playboy, on the face of it, offers ample room for yet another rehearsal of the “porn-exploitative/porn-empowering” debate to rack recent feminisms). Instead Preciado takes hir subject completely seriously: “Playboy is for the contemporary critical thinker what the steam engine and the textile factory were for Karl Marx in the nineteenth.”3 If Playboy is the site of contemporary production into whose hidden walls we must attempt to enter, who or what is it producing?

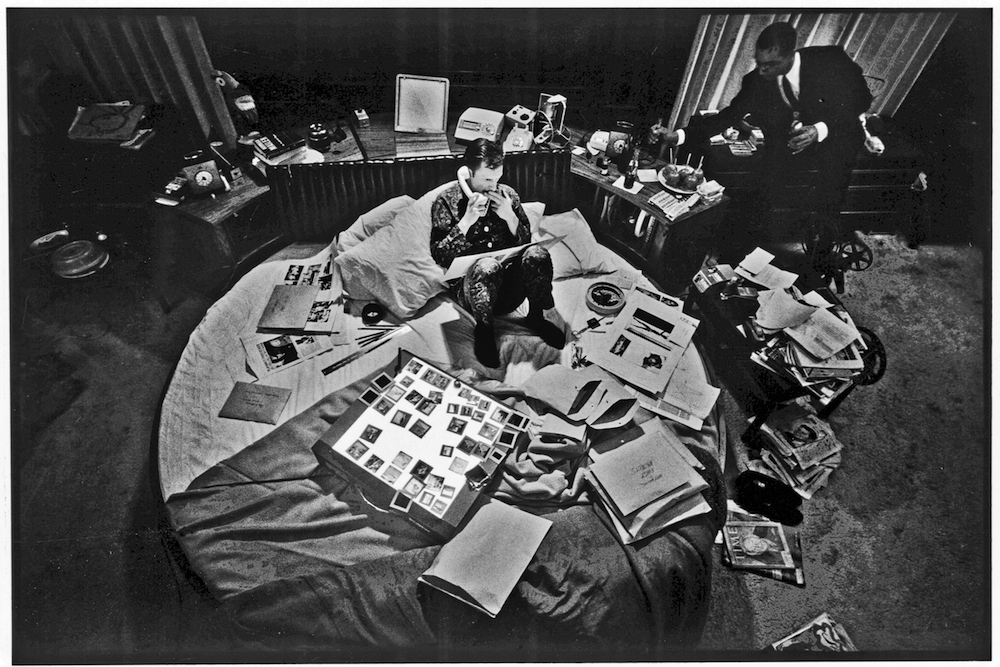

Preciado begins not with Hefner, the bunnies, the magazine or any other of the other obvious Playboy images, but with Hefner’s relationship to architecture. Preciado’s answer to the question of what Playboy produces is “pornotopia,” a space and a map that constructs “hegemonic heterosexual masculinity within capitalism.”4 But it also does so much more than this. Picking up on a photograph of Hefner posing next to a mock-up scale model of the first Playboy Club (in L.A.), Preciado compares the image to a strikingly similar image of Le Corbusier holding a high-rise building. Playboy is far less the magazine, Preciado argues, than it is an “architectural multimedia production company.”5 Throughout the text, Preciado deploys multiple images of planes, vectors, hubs, exteriors and interiors to describe the way in which Playboy functioned to sculpture a “new masculine soul,” with Hefner as the pioneering, jittery master of the domain, experimenting on himself as much as on the millions of readers who encountered the magazine in the 1950s and ’60s. It is Hefner who videotapes his bed-based encounters, sexual and business, logging every encounter from 1952 onward. It is Hefner who spends hours editing these recordings in his editing suite. It is Hefner who paradoxically takes Dexedrine in bed, allowing him not to sleep, but to remain awake, losing all sense of day and night. It is Hefner who understands his own production as architectural as much as it is sexual. In reality, it is the buildings that come first, and the sex is just an afterthought. Sleep tight.

Far from the historically rugged, outdoorsy hunter image of white American masculinity, Hefner represents a new kind of man, an “indoors man,” who pursues pleasure and hedonism purely within the walls of his bachelor pad. In order to do so, he has to recolonize and rid domestic space of any of its feminine associations—a tough job to do when female domesticity was being forced on millions of unhappy women in the period after World War II (creating such a widespread sense of anxiety and medication that Betty Friedan would refer to it as the “problem with no name” in The Feminine Mystique). In order to do this, the nuclear family would have to be shunted out of this space in its entirety, creating, against the heterosexual family home “a parallel utopia” of the urban bachelor. The Playboy home, Hefner’s own just being the most paradigmatic example, was a “refuge for the exhausted just-divorced male,” a kind of incubator that was equally shielded from the demands of domesticated women (a bunny is not a wife, and is always fun) as it was from the threat of male homosexuality (the image of masculinity produced may have been “indoor-sy” but it was very much along the oversexed spy-Bond model, with technologies and décor that hinted at a new kind of male power and consumer power).6 Men could hang out with one another, but the bunny-type girl-next-door would come over just about often enough to prevent any untoward rumors—of the kind that would promote a louche sort of appropriate, heterosexual intrigue. This “post-domestic” space was occupied then by a type of teenager, however old: “a variant of the new apolitical consumer created by the society of abundance and postwar communication.”7

Preciado’s brilliance at capturing the multiple dimensions of the Playboy pornotopia leads us through myriad reflections on technology, toys, exhibitionism, privacy (“the male pleasure of seeing without being seen”), the history of brothel architecture, birth control, cleanliness and the role of theater in the production of Playboy subjects.8 Preciadio’s prose is vivid and convincing, and utterly visceral: Hefner is not merely symbolic of the pornotopia he promotes; he is “a mass-media Plato in a porn cave,” living out the dream that he repeatedly sold to millions of Americans who were transformed by the bachelor-architectural fantasy, even if they were in reality stuck at home with their wives and children and a bunch of magazines hidden in the back of a closet.9 As much as Preciado focuses the research through the architecture, the magazine itself, and the photography and articles inside, doesn’t get overlooked.10 Her account of the centerfold, for example, is highly convincing: “a rotational, nondirectional space where the model could be seen from any point of view.” Pornotopia, like Hefner’s rotating bed, is a directionless site out of which any fantasy can be projected, so long as all of them are utopian (I am reminded of Alexander Deyneka’s ceiling mosaics in the Mayakovskaya metro station in Moscow, designed to represent the twenty-four-hour Soviet sky, where figures reach into the infinite future).

Preciado’s main focus in relation to the magazine, and this is the absolutely key aspect of the analysis for me, is the way in which the production of the magazine itself prefigures the general transformation of work into leisure, with Hefner’s horizontal editing process (from bed, on his carpeted floor) prefiguring post-Fordist work in which “Playboys blurring of the Fordist distance between labor and sexuality, between publicity and privacy could be understood as a paradigmatic example of the transformation of the working practices within neoliberal economies in the second half of the twentieth century.”11 The Playboy empire is no longer simply a kitschy cultural phenomenon, but a forerunner of a “new relationship between production and consumption materialized within the process of communication.”12

The fact that Preciado’s vivid analysis, which covers so much ground already, can make such convincing claims about architecture, work, and sexuality is a testament to the eclectic but rigorous way in which s/he approaches hir topic. A brief postscript makes it clear how hard it was to get access to the “highly disciplined and monitored” Playboy archives, turning Preciado’s project into a “more in-depth exploration of the relationship between the representation of sexuality and biopolitical regimes.”13 14 Playboy’s censorship is our gain, however, for Preciado has constructed a methodology and a piece of work that tells us far more about the second half of the twentieth century than we could have possibly imagined, no matter how many rabbit holes we might have already tumbled into on our own.

-

Beatriz Preciado, Pornotopia: An Essay on Playboy’s Architecture and Biopolitics (New York: Zone Books, 2014), 61. ↩

-

Preciado, Pornotopia, 10. ↩

-

Preciado, Pornotopia, 10 ↩

-

Preciado, Pornotopia, 10. ↩

-

Preciado, Pornotopia, 18. ↩

-

Preciado, Pornotopia, 35. ↩

-

Preciado, Pornotopia, 48. ↩

-

Preciado, Pornotopia, 42. ↩

-

Preciado, Pornotopia, 122. ↩

-

And indeed there are plenty of other places to look if you want a more historical, factual account of the magazines themselves. ↩

-

Preciado, Pornotopia, 53. ↩

-

Preciado, Pornotopia, 54. ↩

-

Preciado, Pornotopia, 226. ↩

-

Preciado, Pornotopia, 227. ↩

Nina Power is a Senior Lecturer in Philosophy at Roehampton University. She writes for several magazines, including New Statesman, New Humanist, Cabinet, Radical Philosophy and The Philosophers' Magazine, and is the author of several books, including, most recently, One Dimensional Woman.