Reality, Flattened

Alongside his many well-known photographic investigations of torture and abusive practices by US military personnel at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, filmmaker Errol Morris dissects an 1855 photograph from the Crimean War, titled The Valley of the Shadow of Death, by embodying the psyche of its author, British photographer Roger Fenton. This photograph has been the subject of much scrutiny given the existence of two nearly identical but distinct versions of it. The difference between them lies in the varied distribution and number of cannonballs in the foreground of each image. Through extensive examination and from cues taken most evidently from angles of shadows, Morris asserts that the cannonballs have been strategically moved around on-site by Fenton and his crew to hyperbolize the war-ravaged landscape that the photograph of the space in its found condition could not otherwise portray.1

By their nature, the way photographs define reality is not so straightforward. If a photograph is a snapshot or proof of the physical existence of objects in an environment, where does authenticity start and end?

As in any other image-making practice, the purpose of a photograph is arguably to convey, with the utmost expressive capability, a story much larger than the extents of the flat surface and finite rectangular boundary within which it rests. The most an image can do, be it a photograph, a painting, or a drawing, is to project—to simultaneously convey and be interpreted. But whereas what it conveys is fixed by the author, its message in the minds of observers is ever evolving and alive indefinitely.

In photography, the depicted reality, be it true, false, or somewhere in between, must be constructed first, and the image produced second. Whether the scene was staged or altered from the found condition in Valley of the Shadow of Death, the photograph still represented a version of a physical reality. With drawing, however, the reality it projects is always a false manifestation of the image that preceded it. A two-dimensional projection cannot convey a singular three-dimensional reality. By definition, a projection—the flattening of information—omits data from the third dimension. It is, by necessity, ambiguous.

On Translation and Projection

In positioning the relationship between the authenticity of a work of art and its author, philosopher Nelson Goodman argues that “a work of art is autographic if and only if the distinction between original and forgery of it is significant; or better, if and only if even the most exact duplication of it does not thereby count as genuine.”2 The definition of forgery in this context is charged, because many arts rely on some form of translation to fully manifest the art. Goodman thus makes a loose distinction between two kinds of art: autographic (usually one-stage) and allographic (usually two-stage).3 Painting and photography are autographic as the artifact itself is the end-product. Music, choreography, and a manuscript for a play, on the other hand, are allographic; they use notation to translate their production into another medium. A musical score is a piece of (autographic) art created by the composer, but its interpreted performance, delivered to an audience by a musician, is a piece of art in its own right. There can be infinite performances and interpretations, each of which is considered an authentic production. Significantly, the audience engages more actively (if not exclusively) with this secondary translation of the work rather than with the autographic score itself.

Architecture is similar in this way, though its processes fundamentally challenge the binary categorical distinction between the autographic and allographic arts. In the production of notation (drawings and written specifications), architects craft a language and a set of conventions that operate to communicate spatial relationships and, importantly, instructions on the execution of those spatial scenarios. However, despite the rigidity of the conventions of drawing, the process of constructing an idea from a drawing is more of a multistage than two-stage art. It involves not only the architect, whose drawings are interpreted by a contractor, but also the subcontractors who receive instructions from the general contractor. Beyond that it is ultimately the builder—the bricklayer, stonemason, welder, plasterer—who leaves a trace of their labor in the field, an actor in the process of construction that is several degrees removed from the architect.

In his essay “From Score to Sound,” musicologist Peter Hill argues, “Many performers refer to scores as ‘the music.’ This is wrong, of course. Scores set down musical information, some of it exact, some of it approximate, together with indications of how this information may be interpreted. But the music itself is something imagined, first by the composer, then in partnership with the performer, and ultimately communicated in sound.”4 This statement is not dissimilar from historian Robin Evans’s claim that “architects do not make buildings; they make drawings of buildings.”5

Unlike many allographic types, though, the conventions of architecture allow very little room for interpretation. This is not without reason, as the primary purpose of producing drawings of buildings is simply to translate the architect’s design ideas to consultants and builders, whose ability to execute the work to a high degree of accuracy to the design’s intent rests almost exclusively on the legibility of the drawing. An important disclaimer is that according to the AIA guidelines, textual specifications, which are one component of construction documents alongside the drawing set, override the drawing. In other words, if the written documents and drawings disagree, the contractor must follow the textual specifications rather than the linework. This stipulation, built into the legal structure of our practice, affirms that no matter how stringent the conventions of drawing are, the medium of drawing is not entirely trustworthy. It can be confusing, lack sense, or, at worst, cause harm. Legibility in a drawing relies precariously on assumptions and conventions that are agreed upon as a disciplinary or professional community. But even in the case of skillful execution and attempted clarity, it is almost impossible to avoid ambiguity in graphical notation. It insinuates that an idea is more likely to be erroneously expressed in drawing than in text and that a drawing is also more likely to be misinterpreted than the written word.

Nevertheless, in the practice of architecture there is no tool more powerful, potent, or elusive than the two-dimensional drawing. Note that I am specifically referring to drawings—a series of points and curves on a flat plane—and not the broader encompassing “image” that could include renderings, screenshots, or photographs. The drawn line is the primary means by which practitioners have historically projected the language of space but, just as it is powerful in its ability to represent, the drawing is equally powerful in its ability to misrepresent—even deceive.

The issue examined here, beyond the inconvenience of misinterpretation in the translation of drawing to building, is that the two-dimensional line is, in the end, rather fickle. Its power starts and ends in the representation of an idea, not in the manifestation of it. Understanding the implications of the process of this translation from drawn line to physical reality can allow a more critical positioning of the history and potential of projection as architecture’s dominant operation. This essay attempts to situate the relationship between not just drawing and building, but also between drawing and its many audiences—the actors who interpret, construct, and ultimately experience the three-dimensional projections of these flat inscriptions.

Projection is a two-way operation depending on its application. On the one hand, it implies the flattening of three-dimensional information onto a two-dimensional plane. On the other hand, projection is the extrapolation of a three-dimensional form from a two-dimensional image, of which there can be multiple potential interpretations. When we observe drawings, photographs, film, and even text, we create an entirely imagined world in our minds from the selective information we are given. As such, projection itself becomes spatial. And, in either case, projection means creating more from less, a process of fabrication, invention, and storytelling.

This essay provides examples in two practices that, though intertwined, each rely primarily on one version of projection: either projecting from flatness or projecting into flatness. Due precisely to the nature of the projective drawing as an ambiguous abstraction (its greatest power and limitation), these practices yield enormous political and ideological consequences. One practice in which the former is used is the translation of drawing to building; one in which the latter is used is cartography and land surveying, which in many ways can be described as building to drawing.

Cartographic Tales

In his series of charts, maps, and other diagrams representing the African slave trade, American sociologist, historian, and civil rights activist W. E. B. Du Bois proposed a map of the globe that split the world into two adjacent circles, tangent along but separated by the Atlantic Ocean. With an inscription that reads, “The problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color-line,” the map explicitly represents the world through the forced migration of Africans across the Atlantic along the Middle Passage. The slave trade becomes the primary driver of formal decisions in this flat, limited pictorial space. The first thing we “see” when we look at this map is a statement of twoness: there’s west and there’s east, two closed figures forcibly pulling toward each other. Curiously, none of the straight lines representing the routes of the slave trade, connecting the eastern edge of the Americas to the western edge of Africa, go through the point of tangency where the two circles meet. Each of the four lines breaks when it hits the circumference of the circles. Though the two sides of the globe are carefully placed in the most intimate of positions with each other—a point of tangency, the purest, most seamless, and natural definition of a transitional threshold between discrete forms—the trade route is drawn as decisively incongruent, hinting at the notion that this massive operation was anything but an inevitability.

Cartographic techniques are some of the most overt practices of subjective translations of representation and reality. Most recognizable maps of the globe are “conformal”—types of maps in which at least one geometric variable is preserved in the process of flattening the globe onto a plane. It is impossible to preserve all variables in the process of representing a sphere on a plane as it is not an isometric translation—spheres cannot unroll to a flat plane without distortion. There are hundreds of different projections of the earth—conformal and otherwise—each of which is useful for different purposes. Some are better for navigation while others are better for more accurate representations of landmasses, and so on. The French cartographer Nicolas Auguste Tissot developed a notation system to reference the degree and directionality of distortion in various maps. Now known as the Tissot indicatrix, distortions of circles (or partial spheres on the globe’s surface) are represented as ellipses superimposed onto the drawing of landmasses in map projections, indicating the degree and direction in which shapes of territories (and hence relative proportions and areas) are distorted—the more eccentric the ellipse, the larger the distortion of the landmass along the ellipse’s major axis.

The Mercator projection, the most widely recognized, is useful for navigation charts because straight lines on the map are lines of constant true bearing, allowing navigators to plot straight-line courses. But, as we know all too well, the Mercator is grossly inaccurate in its representation of the relative sizes of landmasses, inflating the poles of the globe and, largely, colonizing powers (regions where the ellipses are most eccentric) while diminishing equatorial territories. In recent years, many classrooms have started adopting the Gall-Peters projection in lieu of the Mercator, an equal-area map, which distorts the shapes of landmasses but preserves their areas, representing their relative sizes more accurately.

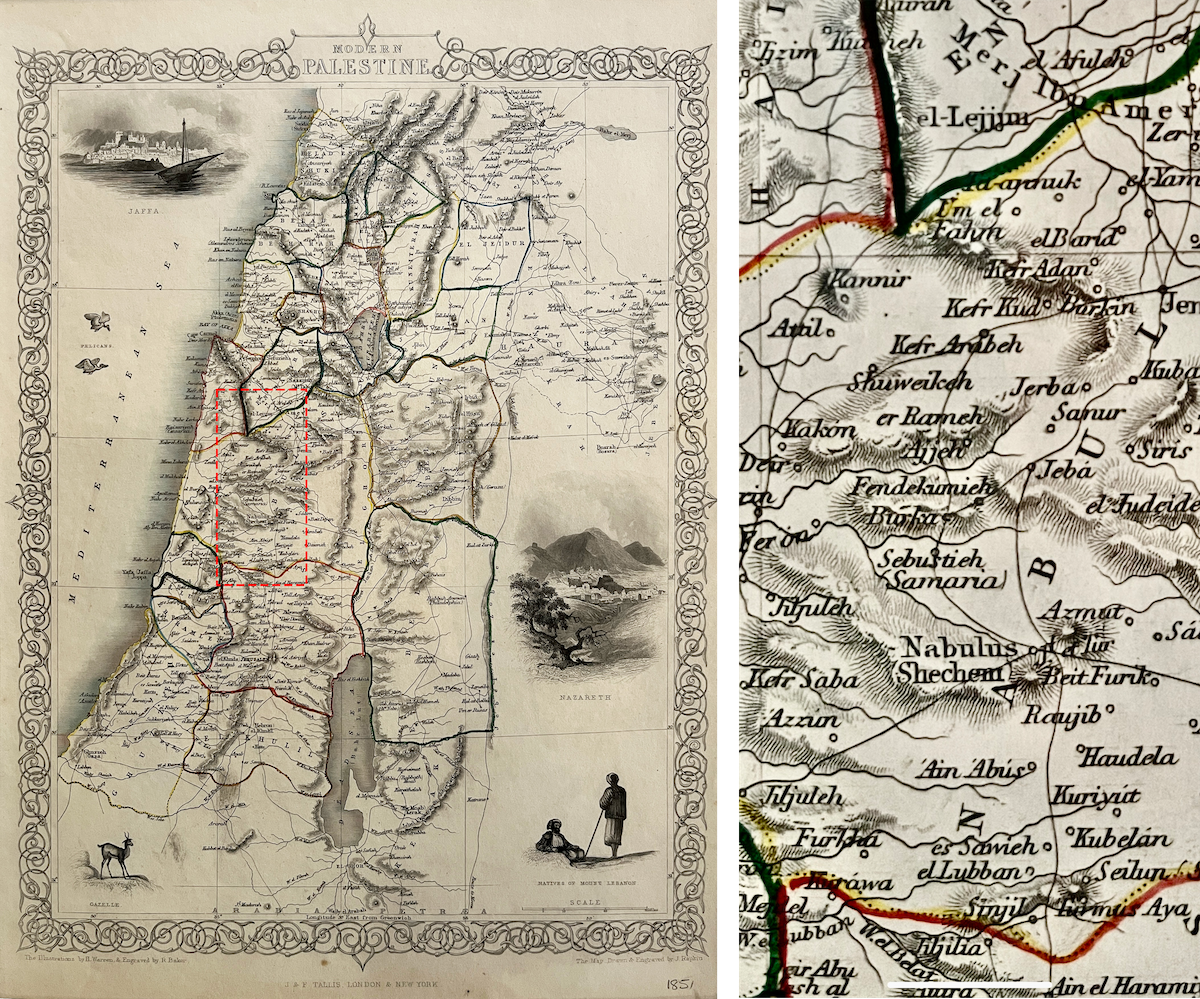

Of its many purposes, the charting of maps serves to transform phenomenologically experienced space as an object to be operated on. Historian Nadia Abu El-Haj argues that cartography presents territory as “a concrete, coherent, and visibly historic place, a sustained object of scientific inquiry.”6 Cartography’s highly charged nature activates many facets of the act of projection, implicating text as a political actor just as much as the geometry of the drawn line. As with many a territory deemed terra incognita by Western explorers, the surveying of historic Palestine—as a land to be discovered, studied, understood (and in many ways, claimed)—was a process of transcribing physically perceived data—whether through topographic measurements or verbal accounts—onto the drawing board. Much of the topographic geometry of what was known for a long time as “Arabia Petraea”—the area stretching from the Sinai Peninsula up to the southern Levant through the “Arabah Valley” and the “Akabah Mountains,” the desert region now more commonly referred to as the Naqab (or Negev, in Hebrew)—was documented in the early to mid-nineteenth century through separate but interconnected expeditions by four explorers preoccupied with the discovery of the Holy Land: German cartographer Heinrich Berghaus, British naval officer John Washington, American theologian and scholar Edward Robinson, and French explorer Jules de Bertou.

The routes of the expeditions differed: Robinson’s route, in April 1838, leaned westward and went from south to north, while Bertou’s, a few years prior, went from north to south and back up north along the eastern side of the desert.7 Each explorer believed their collected data was the most accurate to date, claiming superior routes and more legitimate local sources that allowed for more effective syntheses of written, oral, and visual information. After first drafting a map in 1835 that included only Bertou’s findings, Berghaus eventually consolidated the explorers’ disparate measurements and information into a single map and, in 1839, published an updated version and first comprehensive map of the region, titled Part of Arabia Petraea and Palestine, in the Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London (JRGS).8 This effort of consolidation, though dismissed by the geographers, was due in part to a (now seemingly trivial) budgetary imperative. The cost of printing led to a desire to conflate multiple routes taken by surveyors—specifically, the routes taken by Bertou and Robinson. “As it is, the engraving of the little maps in our volume cost us about 150 pounds annually… the routes of these two travelers are so separate that they do not in the least interfere with each other,” Berghaus wrote, though the geographers themselves would beg to disagree.9

The cost of printing aside, the construction of this now infamous map was not without its own intrinsic controversies. Originally intending to publish only the findings from Bertou, Berghaus expressed the difficulty of ignoring the meticulously detailed textual descriptions of Robinson and his traveling partner, Eli Smith, claiming, “The observations of these two travelers was so full and comprehensive; their notes upon the form and the features of the country so exact and definite; that the Geographer is in a situation, on the basis of these specifications, to construct a special Map of the territory.”10 That special map was the composite published in 1839, which preferred a distorted representation over a more coherent, uncontested account by a single geographer. Reconciling disparate information from both text and line resulted in a compromised representation of the Dead Sea—an average of sorts—and misalignments between relative locations of specific land markers. This distorted map contained, paradoxically, more information than one that would have relied on Bertou’s physical measurements alone, as it represented the composite of multiple accounts rather than only one. The detailed textual descriptions proved more convincing to Berghaus than Bertou’s drawings on their own. Unlike the distortions in the Mercator map, here geometric distortion is indexing competing empirical narratives and, notably, is a result of a battle between the drawn line and the written word. Perhaps it is worth remarking that, on the note of territories being “objects to be operated on,” the point of pride in Berghaus’s map lay neither in the nature of the information it conveyed nor in the stories it uncovered of the land and its inhabitants. Rather, these geographers reveled in the map as a feat of demonstrating not only an “Anglo-German scientific cooperation but also rivalry.”11 This was the first map to exist of the region with such thorough visualization.

From Scientific Object to Ethnographic Narrative

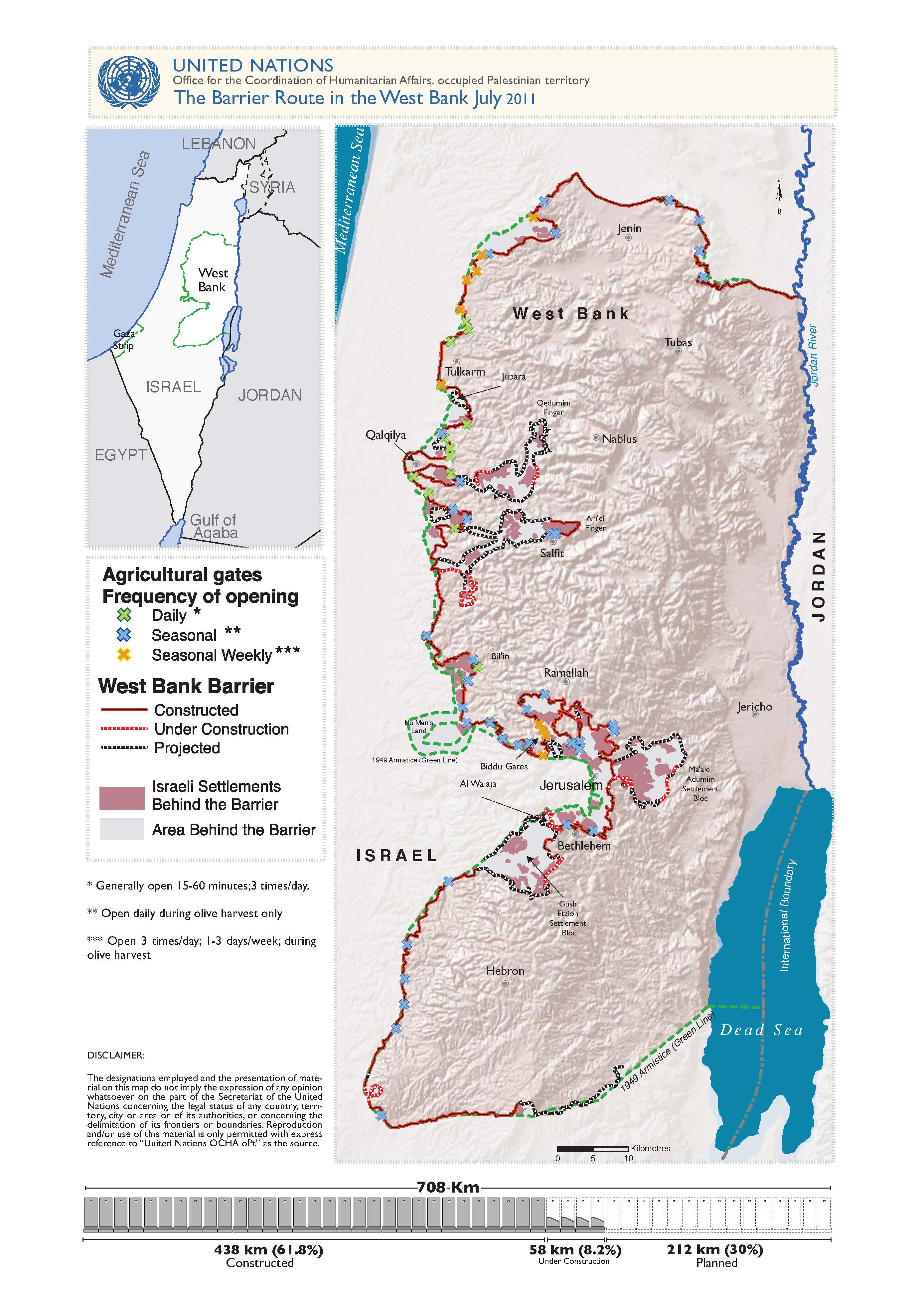

As the Royal Geographic Society and Royal Engineers set out to expand on the surveys these explorers began, factors beyond rivalry or inaccuracy in measurement began to seep into the motivations behind new cartographic studies of Palestine as a territory to be studied and understood. Leading up to the British Mandate, maps were drawn as a way for the British Army and the Jewish Palestine Exploration Society to not just understand the existing geological conditions of the land but also reinterpret its narrative, turning cartography into a medium for storytelling more so than discovery and exploration. Indeed, this practice continues today in a similar form; maps of Israel-Palestine are often represented in multiples or in juxtaposition with one another, illustrating the evolving history of territorial boundaries, namely, representing graphically the shrinking of Palestinian territory over the decades since 1948, or otherwise the misalignments between agreed-upon borders and constructed ones (such as the route of the border wall meandering around the Green Line).

Abu Al-Haj argues that, beyond verbal or written storytelling by natives of a land and beyond visual cartographic practices themselves, it is archeological inquiry that ultimately serves to bolster a desired constructed narrative for the physical and ethnographic history of a place. Importantly, she makes a case for observation of physical space as a mediator between text and drawn line. She writes,

It was precisely through the work of excavating that the fund intended to produce knowledge of a very different kind. Textual traditions would be taken as an “indication, not as an authority.” They had to be supported “by other evidence,” which would be derived from firsthand experience and observation of material proof gleaned from the landscape and from the depths of the earth itself. In this quest for observable truths, however, not all things visible (or, more accurately, not all things potentially visible) were to be of equal value… That landscape could be scientifically explored (excavated as opposed to “mere purposeless digging” only subsequent to the drawing of accurate plans and to the “actual measurement and a careful survey of the modern” city of Jerusalem or of the country as a whole.12

Notice that, here, textual or verbal description is decidedly superseded by the drawing, which is only made possible via the relationship between text and observable truths; this yields a complex feedback loop between text and line, and ultimately establishes their reliance on each other as a necessary partner in constructing narrative.

She continues, “Maps, in other words, were a prerequisite for archaeological research. And it was precisely for the extrication of historical truth via cartography (the primary science) and, thereafter, informed excavation that the fund turned to officers of the Royal Engineers.”13 Primarily, however, historians argue that mapping the territory served a more profound dominant purpose: not to understand its physicality but rather to learn about and recast its ethnographic history. Most of the maps of modern-day Israel-Palestine used by the Zionist movement of the late nineteenth century were drawn by European—primarily British—cartographers and engineers (there are very few known maps drawn by natives—whether Muslim, Christian, or Jewish, or other inhabitants—that were used as the standard reference for subsequent military or geopolitical strategy).

More remarkable than the lines on these maps delineating borders is the text—the paired names of regions, cities, and towns, each of which had its transliterated name in Arabic paired with either the biblical name of that town, in English, or a Hebraized version of the name taken phonetically from the Arabic. The pairing of two names—one known by natives living on these lands, and the other a proposed name for the future identity of the place and its new inhabitants—is a prime example of the way maps have been used as tools to craft new narratives. The inclusion of two names, represented nonhierarchically and equally, imposes the two identities as temporally coexisting rather than one representing the present and the other, a projected future. Notably, the earlier maps drawn by Berghaus, Washington, Robinson, and Bertou were inscribed primarily with the Arabic place names according to standard orthography developed by Swedish biographer Jacob Gråberg di Hemso.14 It is only when the maps were redrawn and updated in preparation for the British Mandate that the Hebraized or Biblical English names began to appear alongside the Arabic.

If we are to understand this role of drawing in both territorial definition and discovery, maps become quite similar to photographs. They represent ideas that people have of what a place ought to be like—the shapes of its borders, its subdivisions, its size, its topography—but present themselves as though they are a true snapshot of reality. As such, the use of a map as a canvas to further draw and plan territorial definition compounds the dissonance between representation and reality. In the case of such contested territory, however, particularly with regard to the role of archaeology, cartography is characterized not by either one or the other type of projection described earlier, but by both. It is, on the one hand, a fabricated truth (maps were drawn first—based on observation of objects on and above the surface of the landscape—to properly understand the depths of the space below the ground plane), and a stencil to justify continued exploration—a literal roadmap—on the other. It serves as both a plane onto which reality is projected and as one to be operated on and projected from. The mapping of historic Palestine, as with numerous contested, discovered, or colonized territories around the globe, served to showcase existing knowledge and, simultaneously, as a catalyzing template to create new stories about the same place. The duality of the aboveground and the underground, the visible and invisible, the known and the undiscovered, confirms that the presupposition that a flat drawing exists on a single plane in three-dimensional space is paradoxical. As we continue to confront over and over, in any practice of image interpretation, a drawing is anything but flat; it is a composite of an infinite number of planes along the axis normal to it.

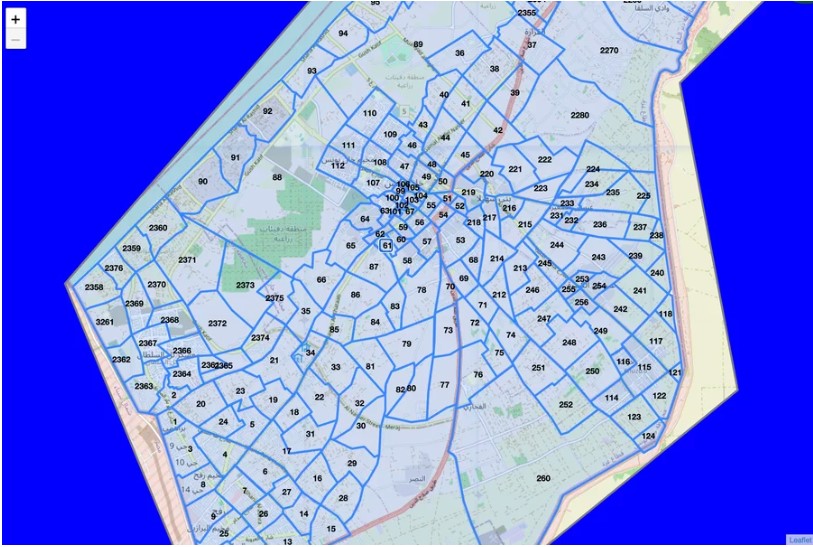

In her essay “In Free Fall: A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective,” Hito Steyerl recalls Eyal Weizman’s argument that “geopolitical power was once distributed on a planar map-like surface on which boundaries were drawn and defended. But at present,” she continues, “the distribution of power has increasingly come to occupy a vertical dimension. Vertical sovereignty splits space into stacked horizontal layers, separating not only airspace from ground, but also splitting ground from underground, and airspace into various layers.”15 This notion is, perhaps not unironically but nonetheless eerily, captured in a photograph of leaflets dropping down from the sky onto residents of Gaza with evacuation orders from the Israeli military during the war in 2023–4 (Figure 6). These evacuation orders were accompanied by an interactive map of the neighborhoods of southern Gaza, sent to residents via text message. The Israeli military divided the region into numbered zones, new and unfamiliar boundaries imposed onto a territory known otherwise by its residents. Verbal instructions on the leaflets did not align with the visual information depicted on the map, causing lethal confusion among Gazans as they struggled to orient themselves and locate their residences in this newly crafted map of their home.16

A single flat plane will never sufficiently represent the stratified space described by Weizman. This argument can be expanded further, literally, in acknowledging that the consequences of the representation of geopolitical power, particularly in the drawing of borders, are not only vertically stratified but also radiate horizontally across vast expanses of the land.

The Fickleness of the Drawn Line

One of the most consequential and tangible translations of the drawn line exists in the realm of territorial definition. Borders manifest in various ways as physical expressions of a drawn line—an abstract, infinitesimally thin, constructed artifact. Geographical borders are, by their very nature, imaginary constructs. The representation of any form of cartographic projection of the earth on a plane is distorted in one way or another. However, they are also constructs in that they are rarely if ever absolute and real. Borders are fluid and thick. They are contrived, always inviting distinctions between the drawn line and the experienced line (or the real and the perceived, though in this case the definitions of “real” and “perceived” can be interchangeable). However, borders extend beyond cultural identities, ethnicities, politics, and language. Migrating birds acknowledge neither drawn lines nor physical barriers. As it turns out, neither do radio signals.

In scenarios where borders are literally constructed, they come in many forms as dimensional extensions of the one-dimensional line—vertical extrusions in the form of walls or fences, splitting space into two absolute sides, or blurred volumetric approximations that hover in the vicinity of the thin drawn line. In her essay “Border/Skin” the architect Lindsay Bremner recalls the spatial zones known as “Bantustans” in apartheid South Africa, as territories or “homelands” that delineated separation more so than any manifestation of an extrusion of a line into a wall:17 “The wall is not a familiar trope through which apartheid was lived or its experience recalled. Any attempts it made to draw boundaries were fluctuating, porous, and ill-defined.”18 Extending this notion, sociologist Anne Shlay and geographer Gillad Rosen build on urban scholar Joel Kotek’s definition of a “frontier city” to argue, “Indeed spatial boundaries, even when seemingly created by topography, are dimensions and creations of culture; there is nothing intrinsic about a border between a city, country, or state.”19 Urban historian Dolores Hayden asserts that “place making” is, after all, an eternal and ongoing act.

Even in cases where a thin line is simply extruded into a vertical surface, political processes beyond the construct of drawing and the physical artifact intercept the translation from two dimensions to three. Because of its crenellations (the deliberate misalignment between the drawn line and the constructed line), the Israel-Palestine Occupation Border Wall currently measures over 700 km in length—about twice as long as the (imaginary) Green Line, the demarcation line agreed upon in the 1949 armistice agreement between Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and Israel following the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. Testament to its precarious and fictional nature, the Green Line—named for the green ink used to draw it—was indeed simply erased from official maps by the Israeli security cabinet in late 1967. Israel justifies the meandering of the wall beyond the Green Line by claiming security concerns in and around settlements that have already been constructed outside the bounds of what is recognized as legal by both the International Court of Justice and the Israeli Supreme Court. The more technical claim, though, is that the topography along segments of the Green Line route would render the eight-meter-tall wall less effective as a barrier (for example, in hilly areas where visibility over the wall is possible), and in that process, of course, further carved out territory from the West Bank to Israel.

Constructed of 1.5-meter-wide concrete sections, the wall is, in the end, a low-resolution inscription of what a policy of separation looks like: eight meters above the surface of the earth, it is a momentary trace of the topography of the land on which it rests. This floating, and now most visible and recognizable, contour is one that cannot be physically experienced or crossed where it is drawn and constructed, but its intended effects radiate hundreds of kilometers away from its base. In some segments of daily life, the location of the wall and its physical characteristics are invisible and irrelevant yet overtly present. It is experienced not through vision or touch but through longer drives to get from one place to another; it is felt through the hostility experienced at a checkpoint distant from it; it is felt in the freshness (or lack thereof) of produce bought at the market.

No matter the capacity of our tools to preserve fidelity between the drawn line and the constructed one, the translation from two dimensions to three inevitably separates imagination from reality—a sought-after ambiguity in the process of projection. Territorial and nation-state demarcations are fickle lines. A drawing can mean one thing on paper, but the lived reality is anything but a simple extrusion, even in cases where the drawing succeeds building, rather than the other way around (for example, in the charting of maps and the construction of the border wall, whose route is transcribed onto existing maps post-construction). To return to Goodman’s question of authenticity, these case studies make evident that authorship in the “art” of building is arguably more complex than most, if not all, other arts. The translation of drawing to building (or building to drawing) may be defined most authentically not by those who draw or construct or observe the artifact, but by those who experience the consequences of its existence. The power of the line rests in the drawing alone, and no process of physical or geometric translation can supersede forces—political, financial, or otherwise—that are much larger and determine to a vastly greater extent the realities of our spatial constructs.

-

Errol Morris, Believing Is Seeing (Observations on the Mysteries of Photography) (Penguin Press, 2011), 3–71. His analysis follows an observation made by Susan Sontag in Regarding the Pain of Others, and before her, Ulrich Keller in The Ultimate Spectacle: A Visual History of the Crimean War. ↩

-

Nelson Goodman, Languages of Art (Hackett, 1976), 113. ↩

-

Goodman, Languages of Art. ↩

-

Peter Hill, “From Score to Sound,” in Musical Performance: A Guide to Understanding, ed. John Rink (Cambridge University Press, 2002), 129–143. ↩

-

Robin Evans, “Architectural Projection,” in Architecture and Its Image: Four Centuries of Architectural Representation, ed. Eve Blau and Edward Kaufman (Canadian Centre for Architecture, 1989), 21. ↩

-

Nadia Abu El-Haj, Facts on the Ground: Archaeological Practice and Territorial Self-Fashioning in Israeli Society (University of Chicago Press, 2001), 27. ↩

-

On the map, Robinson’s route is marked in red; Bertou’s is in blue. ↩

-

Maps constituted a combination of materials, including “measurements, written and oral descriptions.” For example, Berghaus mentions in his Memoir to the Map of Syria (1835) that to establish the distance from Jaffa to Jerusalem, he relied on varied reports from eight explorers. ↩

-

Haim Goren and Bruno Schelhaas, “Berghaus’s Part of Arabia Petraea and Palestine Map (1839) and the Royal Geographical Society: Misuse or Misunderstanding?” Terrae Incognitae 47, no. 2 (September 2015): 127–141. ↩

-

Goren and Schelhaas, “Berghaus’s Part of Arabia Petraea and Palestine Map (1839) and the Royal Geographical Society,” 135. ↩

-

Goren and Schelhaas, “Berghaus’s Part of Arabia Petraea and Palestine Map (1839) and the Royal Geographical Society,” 130. ↩

-

Abu Al-Haj, Facts on the Ground, 27. ↩

-

Abu Al-Haj, Facts on the Ground, 27. ↩

-

Jacob Gråberg, “Vocabulary of Names of Places, & c. in Moghribu-l-Aksá, or the Empire of Marocco,” Journal of the Royal Geographical Society 7 (1837): 243–70. ↩

-

Hito Steyerl, The Wretched of the Screen, e-flux journal (Sternberg Press, 2002), 23. ↩

-

Kat Lonsdorf, Daniel Estrin, Anas Baba, and Abu Bakr Bashir, “Israel’s Map and Evacuation Messages for Gaza Are Adding to the Chaos,” NPR, December 7, 2023. ↩

-

Lindsay Bremner, “Border/Skin,” in Against the Wall, ed. Michael Sorkin (The New Press, 2005), 122–127. ↩

-

Bremner, “Border/Skin,” 122–123. ↩

-

Anne B. Shlay and Gillad Rosen, “Making Place: The Shifting Green Line and the Development of “Greater” Metropolitan Jerusalem,” City and Community 9, no. 4 (December 2010): 345–446. ↩

Iman Fayyad is an Assistant Professor of Architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design and founding director of projectif, a research design practice that explores relationships between projective geometry and the politics of physical space and building practice.