If I say, My river is disappearing, do I also mean, My people are disappearing?

—Natalie Diaz, “The First Water Is the Body”1

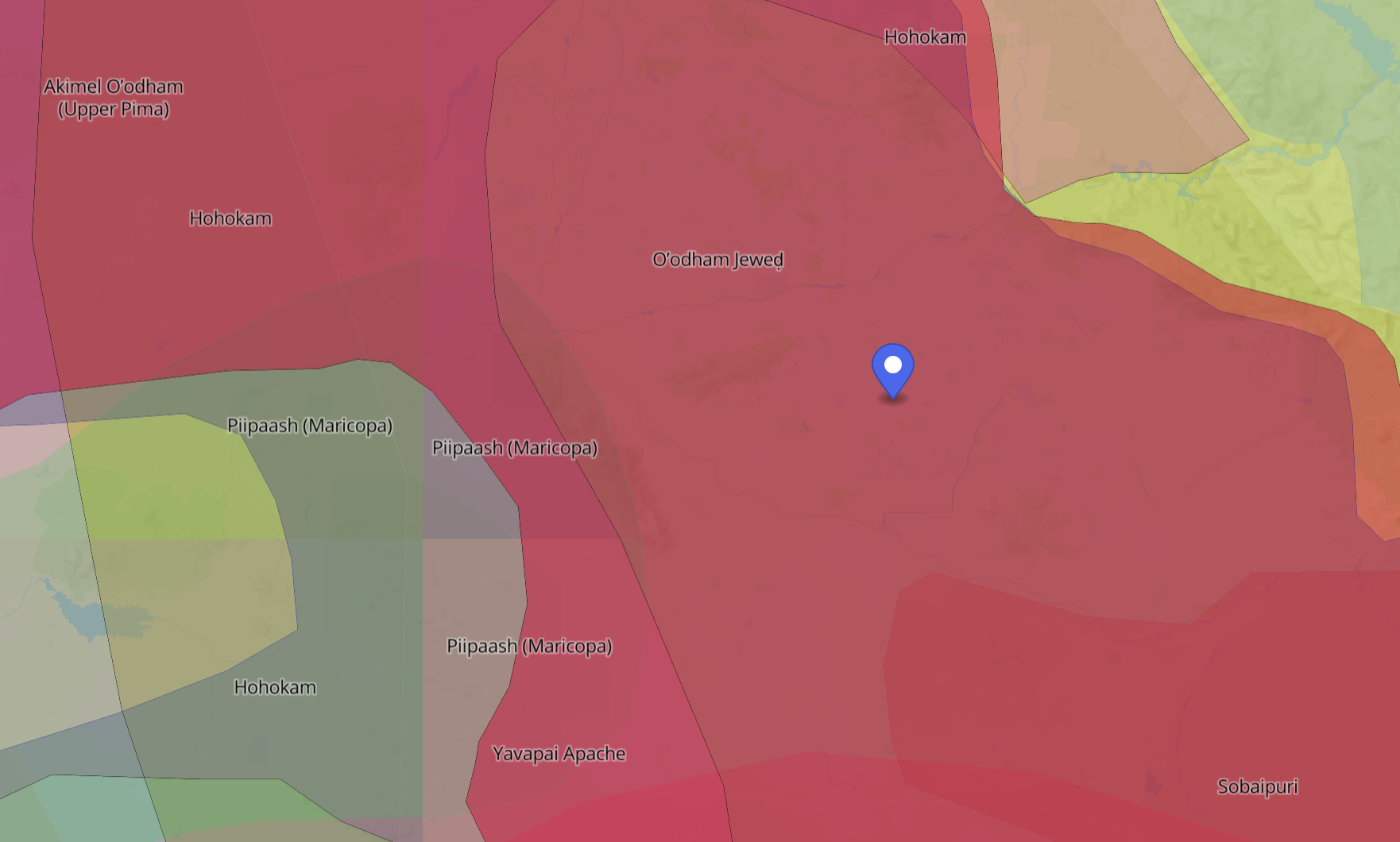

The ocotillo is a semi-succulent plant indigenous to the Chihuahua, Mojave, and Sonoran Deserts. Most months of the year, the plant appears dead—just a cluster of meters-tall thorned sticks that sway slightly in a rare breeze. After the summer and winter monsoons, the branches leaf and bloom sunset-hued flowers. It is a life-giving shrub. Its bark can be used for a tincture to relieve congestion and improve lymphatic health, and its roots can ease fatigue and slow bleeding. Melhok ki (ocotillo house) is an airy structure built by the Indigenous Tohono O’odham and Akimel O’odham people from the ribs of the ocotillo—a space for reprieve from the desert sun.

In 1980, Intel Corporation began operations in Chandler, Arizona, in the Sonoran Desert. By the late 1990s, its Ocotillo campus was manufacturing semiconductor chips used in solar panels, computers, ATMs, refrigerators, pacemakers, and more.2 Boosters of Intel’s presence reminisced:

When Intel first came to Chandler, it didn’t just open a factory—it opened the door to the city’s future. The locations of new freeways, upscale retail centers and luxury housing subdivisions can all be traced in part to the microchip manufacturing giant, its two Chandler campuses and its nearly 10,000 highly paid educated work force.

Since it first arrived in the East Valley... the company has left its mark in ways nobody could have predicted. Indeed, many of the other high-tech companies also operating in Chandler were drawn to the city after Intel set down roots, as were other businesses that have created jobs and helped establish one of the highest median incomes in the Valley.3

Intel hitched itself to the future of the city and state; as the 2023–2024 Community Investment Report states: “For 45 years, Intel has innovated and invested in Arizona, helping to grow an ecosystem of innovation now known around the world as the Silicon Desert.”4 Building the Ocotillo campus rewrote the infrastructure and housing market for this Phoenix suburb—city planners skirted procedure in the interest of expediting profits; private engineering firms helped speed zoning approvals and tax break incentives. But Intel didn’t just remake Chandler architecturally—its influence leached5 into the community in other ways. Since its earliest development phases, Intel partnered with the Chandler Unified School District. Intel employees were encouraged to advise on the district’s science and computer programming curriculum: The company plays a significant role at Hamilton High, where school and Intel officials have been working together on science and math-related curricula since the school opened in 1999. “They changed the way we teach science,” said Fred DuPrez, the school’s principal.6

In other words, in addition to wreaking havoc on the housing market and subsequently on the housing stock in Chandler, Intel aimed to secure the education of generations of city residents to Intel-generated curriculum and to steer a pipeline of youth toward careers in semiconductor manufacturing. The Intel Foundation, established in 1988, continues to funnel thousands of dollars in grants into the Chandler Unified School District as a token “service to the community” while concurrently ravaging the city. Despite settler colonialism’s familiar logics, which frame the Ocotillo campus’s expansion as “blooming the desert”7 and breathing “modernity” into an otherwise sleepy desert town, the Intel campus’s unchecked growth desecrates Indigenous lands and lifeways.

Today, the Intel campus sprawls across 700 acres of this Indigenous land and counting. In September 2021, the company broke ground on Fab 52 and Fab 62, two new semiconductor manufacturing facilities in Chandler, with a project price tag of $20 billion—the largest private-sector investment in Arizona history.8 In March 2024, Intel received $8.5 billion in direct funding from the US Department of Commerce under the US CHIPS and Science Act,9 and an additional $11 billion in loans from the CHIPS Program Office to bolster the Ocotillo campus’s operations.

On March 20, 2024, President Biden, framed by a giant American flag and an array of Caterpillar construction equipment on top of cracked caliche soil, addressed a crowd of stakeholders and shareholders-as-politicians at the Chandler site for a groundbreaking ceremony:

We have invent- — the only nation in the world that have never th- —we have come out of every crisis we’ve ever been in stronger than went we went into that crisis. There’s nothing beyond our capacity.

I’ve never been more optimistic about our future. We just have to remember who in the hell we are. We’re the United States of America. (Applause). And there’s nothing beyond our capacity when we work together.

So, God bless you all. And may God protect our troops.10

That same day, Intel’s media release, “Intel Arizona: The Silicon Desert,” affirmed its long-standing intentions of turning Chandler into the next version of California’s Silicon Valley—securing its financial stronghold on local K-12 schools, community colleges, and universities, and manufacturing consent for workforce development.11 The US Department of Commerce’s National Institute of Standards and Technology “CHIPS for America” confirms as much:

Arizona is already home to massive investments from the Intel Corporation, TSMC Corporation, the Applied Materials Corporation, and many others. Arizona State University [ASU] plays an important role in supporting these corporations through research and development and being able to provide a talent pipeline of an educated and prepared workforce. ASU has been named “number 1 in Innovation” eight years in a row and is home to the largest engineering school in the nation. We have the schools, faculty, tools and resources needed to support and enrich the semiconductor manufacturing industry in Arizona and beyond.12

In addition to Intel, the “Microelectronics at ASU” website lists the US Department of Defense, US Army, and the US Navy as partners.

Also on March 20, the environmental organization Sierra Club,13 alongside CHIPS Communities United—a coalition of labor unions, community groups, and environmental organizations—released a statement urging Intel to follow through on its pledges for chemical handling safety, greenhouse emissions, and just labor practices.14 However, there is no mention in the document of Indigenous land and water rights, remediation efforts, or other infringements on Indigenous sovereignty. The dissonance between corporate “environmental stewardship” and the actual damages wrought on the region’s most vulnerable communities for decades is testament to the greenwashing of capitalist prerogatives of profit over people. Intel’s decimation of the fragile ecology in Arizona is, of course, not limited to Chandler nor to its additional manufacturing sites in Rio Rancho, New Mexico, and Hillsboro, Oregon. Its scorched-earth-as-tech-innovation is part and parcel of the settler colonial claims of terra nullius. This process is assuredly not unique to this region, but for those trained to see solely that which is to be taken, expanses of desert territory, from the Sonoran Desert to the Naqab in Palestine, are lifeworlds to be relentlessly annihilated.

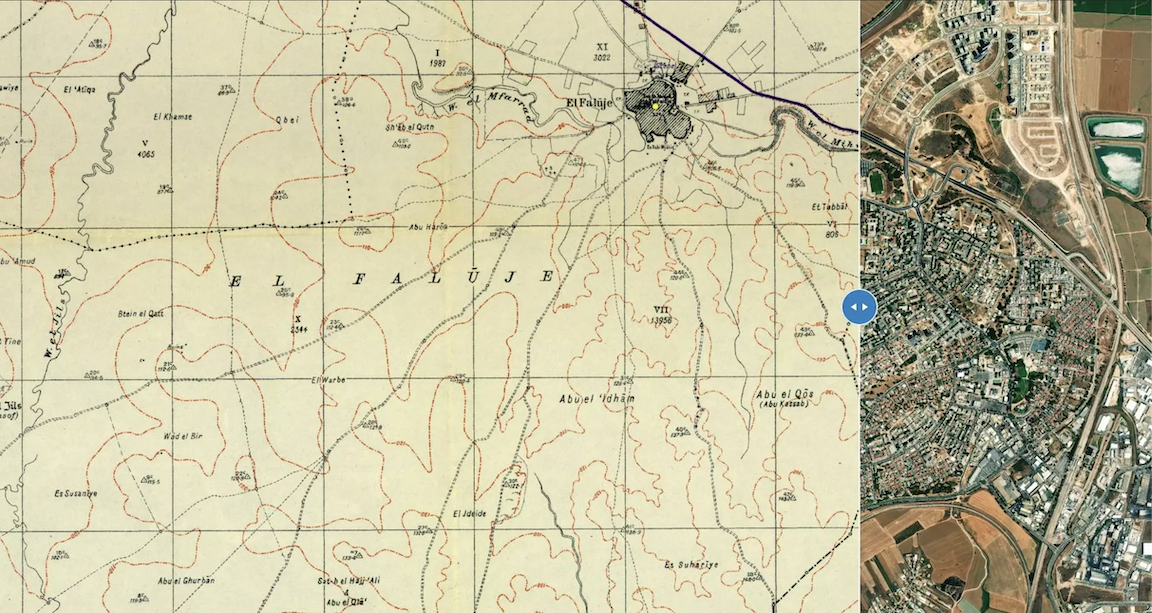

In 1999, Intel opened its Fab 18 chip fabrication plant on the ruins of Iraq al-Manshiyya and al-Faluja, Palestine, within the illegal Israeli settlement of Kiryat Gat. This move in the Naqab marked enormous expansion efforts after the company previously established offices in Haifa (1974) and the Fab 8 manufacturing center in Jerusalem (1982). In addition to the $1 billion spent by Intel on the Kiryat Gat campus, the Israeli government provided an additional $600 million grant to support the sprawl.

Prior to the Nakba, al-Faluja and Iraq al-Manshiyya were thriving centers of commerce, of agriculture, of life. The land, before the Israeli colonization of Palestine, was rich in grain cultivation and grapes; almond and olive trees filled the surrounding rolling hills. In March 1948, a “supply convoy,” escorted by Haganah soldiers, besieged al-Faluja—detonating homes, the town hall, the post office, and other municipal buildings.15 By April 1949, following months of violent intimidation, the remaining Palestinian population of the area was forced into exile.

The Kiryat Gat settlement, which was initially established as a ma’abara (absorption camp), rapidly ballooned during the mid-1990s post-Soviet aliyah. This growth was sponsored by the funding schemes and expropriation operations of the Jewish National Fund–Keren Kayemeth LeIsrael (JNF-KKL)16 and other exploitative donors, including the Ukrainian-born zionist Efraim Margoli. Margoli, an American businessman who also worked for the Mossad, had a heavy hand in the construction of Kiryat Gat, and was a founding benefactor of 40,000 nonnative trees planted as a way to further eliminate traces of the Nakba. Afforestation, here—as across Palestine, and like the desecration of desert flora in the Sonoran Desert—is a weapon of settler colonial land theft. The Plugot Forest and Ha-Mal’akhim-Shkharya Forest choke the remnants of Iraq al-Manshiyya and al-Faluja, while the territory itself has been plundered, razed, and rebuilt unremittingly in the image of the occupier.

The land’s further defilement ahead of Intel’s expansion in Kiryat Gat was not without contestation. In November 2002, the activist organization Al-Awda and a coalition of academics urged direct action against the corporation and sparked widespread support for divestment from Intel.17 Despite dissent from a conscious global network of Palestinian activists, tech workers, and academics, the Intel campus continued to grow. With the success of Intel’s Pentium processor worldwide and billions of dollars in global sales, the development of Fab 28 was announced in 2005. Intel’s stronghold across occupied Palestine is elemental to the boom of “Silicon Wadi,” the glibly named concentration of high-tech startups (many spearheaded by Mamram graduates, the Israeli Occupation Force’s [IOF]18 computer corps) and venture capital groups that pump enormous funds into surveillance, military, and border technologies.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Department of Urban Studies & Planning partnered with Tel Aviv University’s Laboratory for Contemporary Urban Design in August 2012 to prepare “Kiryat Gat 2025.” The strategic plan aimed to imagine (and cross-promote) growth throughout and beyond the settlement. It incorporated stakeholder interviews and geospatial, demographic, and environmental data to “to envision, plan, and design prototypical sustainable residential communities for Israel [in] 2025.” This greenwashes Israel’s ongoing and future presence on and expropriation of Palestinian land, highlighting a “long-term” US research agenda “to plan, design, and retrofit existing residential communities to become low carbon, ecologically responsive, [to] incorporate new technologies, and generally enhance the livability and self-reliance of local residents and potential newcomers.”19 Their “NexCITY Refigured Urbanism” vision emphasized:

The Israeli government has launched policies to solve the problems of distressed neighborhoods, the most prominent among which are “demolition and redevelopment” (Pinui Binui) and densification (Ibui Binui). The idea behind these strategies is to create non-government mandated market conditions that foster initiatives for developers to physically expand their construction projects. Yet, there are many limitations to the current strategies and it is clear that new strategies need to be initiated, in particular for cases of neighborhoods with a majority of low income families and low land values that do not attract for-profit developers.20

The Israeli Government Authority for Urban Renewal, a dedicated office under the purview of the Construction and Housing Ministry, urges for “Pinui Binui” (which translates to evacuation and construction)—state-sanctioned dispossession and demolition of aged housing units—that is, in practice and reality, the slashing and burning of historically Palestinian homes, businesses, religious and cultural spaces, and more under the guise of “renovation,” “modernization,” and attracting foreign investment. Again, state-sanctioned dispossession and demolition of aged housing units: These words evince how genocide, ecocide, domicide (-cide in every form) are cloaked and normalized not only by the “formal” warmongers (Netanyahu, his cabinet, US military/government enablers, “defense” contractors and shareholders) but by architects, planners, landscape designers, academics and university administrators, realtors, artists, and many others.

This process of urban renewal is compounded by the 1950 Absentees’ Property Law21 and 1950 Law of Return22—both of which legally enshrine zionist claims to Palestinian land and generate tremendous ongoing obstacles to Palestinians remaining on their ancestral homelands. In Patrick Wolfe’s evergreen reminder:

Settler colonialism destroys to replace. As Theodor Herzl, founding father of Zionism, observed in his allegorical manifesto/novel, “If I wish to substitute a new building for an old one, I must demolish before I construct.” In a kind of realization that took place half a century later, one-time deputy-mayor of West Jerusalem Meron Benvenisti recalled, “As a member of a pioneering youth movement, I myself “made the desert bloom” by uprooting the ancient olive trees of al-Bassa to clear the ground for a banana grove, as required by the “planned farming” principles of my kibbutz, Rosh Haniqra.” Renaming is central to the cadastral effacement/replacement of the Palestinian Arab presence that Benvenisti poignantly recounts.23

While the MIT–Tel Aviv University project is rife with buzzwords that may read to the willfully ignorant as an increasingly egalitarian approach to redevelopment—specifically for the ways it aims to provide housing access to lower-income settlers and migrant laborers—the “Kiryat Gat 2025” vision is ultimately a blueprint for entrenching transnational technology megacorporations such as Intel, and other zionists-as-CEOS and university leaders, in order to hasten the land grab across the Naqab and all of Palestine.24

Structured by words like “challenges ● opportunities ● significant potential ● preservation ● use value ● accessibility,” the 190-page report produced by this collaboration is but one scheme in a more than century-long history of colonial planners, developers, politicians, realtors, bankers, investors—plunderers by many names—redrawing the maps, the property lines, the terms of engagement in the interest of profit and power.25 “Industrial Urbanism,” the project title and operational agenda for MIT–Tel Aviv University, translates—ecologically, spiritually, architecturally—to an ongoing Nakba (al-Nakba al-mustamirra) for Palestinians and their land. This coded language of dispossession, of destroying the desert and the entirety of Palestine, neatly tucked into courses, workshops, municipal projects, and so forth, normalizes and routinizes the ongoing ravaging of Palestinian land in the interest of “high-tech innovation.”

MIT’s long-standing commitment to partnerships across Israeli universities and companies is exemplary of the US academy’s entrenchment in the zionist settler colonial project. For more than forty years, the MIT Global Experiences (MISTI) program has placed students in over forty countries in fully funded internships, research lab positions, and “global collaboration” projects. For example, the MIT Civil and Environmental Engineering program partners with the National Science Foundation, the United States–Israel Binational Science Foundation, and Ben-Gurion University of the Negev for agricultural microbiology fieldwork courses that include tours, hikes, homestays, and barbecues at kibbutzim. Additionally, the MIT Sloan School of Management’s “Israel Lab” encourages students’ involvement in Israeli high-tech startups:

Why Israel? Israel is home to the highest density of startups in the world. As one of the most dynamic entrepreneurial economies, Israel can leverage its creativity and experience across disciplines for our students. MIT’s motto, mens et manus—mind and hand—emphasizes education through practical application. Israel provides the environment to maximize hands-on learning in world-class entrepreneurial organizations. The Israeli culture and economy, built on teamwork, initiative, and innovation, is the perfect match for the MIT pedagogy and mission.26

As the scholar of Israeli-developed systems of militarism Maya Wind elucidates, universities are complicit in Palestinian unfreedom.27 These insidious relationships—while hardly limited to Ben-Gurion University, Tel Aviv University, and well-known US universities—show the academy’s complicity in (and even commitment to) the prolongation of Palestinian suffering and concurrent profit maximization for stakeholders, sometimes quasi-disguised as philanthropic and educational initiatives but always in the interest of shareholders’ bottom line.

The US imperial project, as the largest supporter and financier of Israel’s “founding” and ongoing 77+ (108+)-year occupation of Palestine, is most notable through the development and manufacture of weapons and surveillance technologies, “field tested” on vulnerable communities and traded globally among warmongers, for billions in profits.

Though drones and missiles are examples of the most nefarious, barbaric tactics of the US/IOF used to leverage their hegemony, they are not all that’s needed to run the US empire and to further dispossess, exploit, and irrevocably harm Indigenous and racialized communities. From study abroad programs to research prizes, curricular collaboration and conferences, the seemingly banal educational and cultural activities promoted and funded by US and Israeli stakeholders further fortify the tacit agreement between settler colonial bedfellows.

It doesn’t need to be this way. When we remain focused, committed, and undeterred by cowardly intimidation efforts, we can (are, will) defeat empire’s hydra.

The Student Intifada of today stands on the shoulders of those like the Social Action Coordinating Committee (SACC), the Weather Underground, the Revolutionary People’s Occupation Forces and the Black Panthers, the Third World Liberation Front, and scores of global grassroots coalitions. SACC’s archives for the years 1969–1975 record decades of organizing against the university-as-imperial-tool.28 In 1969, MIT’s radical student newspaper The Old Mole wrote:

MIT isn’t a center for scientific and social research to serve humanity. It’s a part of the US war machine. Into MIT flow over $100 million a year in Pentagon research and development funds, making it the tenth largest Defense Department R&D contractor in the country. MIT’s purpose is to provide research, consulting services and trained personnel for the US government and the major corporations—research, services, and personnel which enable them to maintain their control over the people of the world.29

MIT’s integral position in US imperial expansionism is not exceptional considering the breadth and depth of so-called Western higher education’s participation in the zionist project. But this university’s self-aggrandizement and chart-topping global rankings for science and technology studies demand our focus toward relentlessly dismantling this Ivory-Tower-as-War-Machine.30

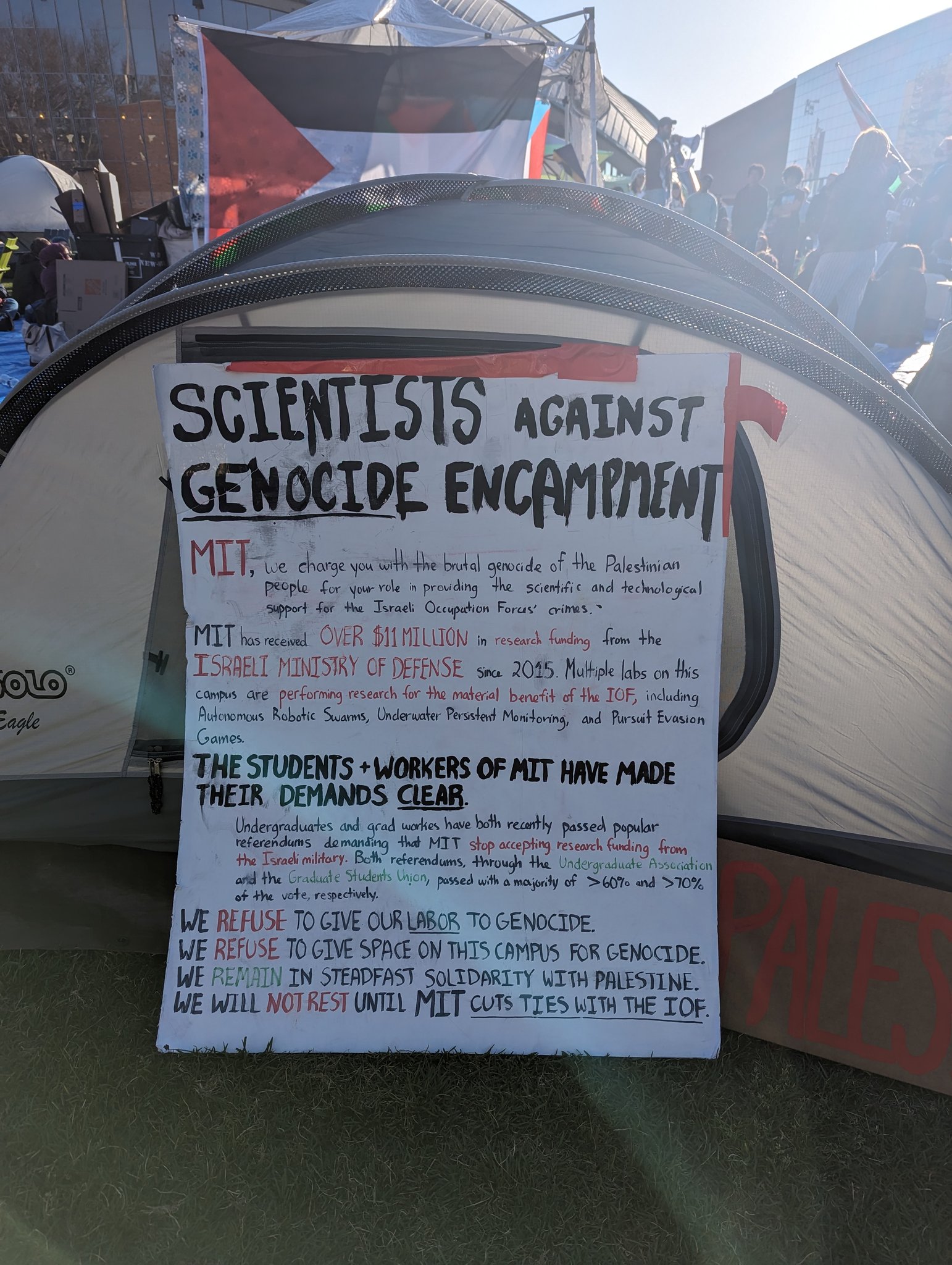

In May 2024, the Scientists Against Genocide Encampment (SAGE) at MIT (MIT Coalition for Palestine) made its multigenerational demands for divestment and justice crystal-clear:

Of course, we have seen these tactics before. In the 1980s, there were similarly heated faculty meetings about MIT’s decision to tear down shanty-town structures on Kresge Lawn built by students protesting MIT’s complicity with apartheid in South Africa. In 1970, at the height of the anti-Vietnam War movement, MIT targeted student-leader Michael Albert with expulsion for “rude and divisive language,” even as the Union of Concerned Scientists and Social Action Coordinating Committee fought to get MIT out of the business of dropping napalm on the Vietnamese. We join our predecessors in demanding that MIT research affirm human life, not build dystopian and militarized futures.* As our colleague Ira Rubenzahl (SACC student leader) told The Tech in 1969: “One doesn’t have the right to build gas chambers to kill people.” To that we add, “One does not have the unqualified right to build drones to kill people.” Academic freedom must have limits; scientific institutions and laboratories do not have the right to collaborate with génocidaires.31

In early September 2024, the MIT Coalition for Palestine announced a major divestment win for its SAGE movement: MIT has ended the MISTI-Israel Lockheed Martin Fund. This is the first known shutdown of an American-Israeli weapons manufacturer partnership at a US university since the current war on Gaza began, and MIT has chosen to end this partnership despite renewing its other MISTI projects.32 This shows the purpose and power of student/community-led coalitions engaging in direct action against imperial domination.

If a university and its constellation of employees, students, and community members are so knitted to settler colonial compulsions, and the careers and lifeways sustained by the logics of ceaseless war and occupation are seemingly tremendously dependent on companies like Intel’s continued growth, how can we insist, stand together, build confidence toward liberatory world-building?

The Student Intifada proves student occupations are effective because they are disruptive. From a Palestine Youth Movement communiqué (May 10, 2024), prophetically precipitating Minouche Shafik’s resignation from Columbia University (August 14, 2024): “We refused to be pacified while the blood of Palestine spills on the streets of Gaza. Instead, we forced Columbia to show the world the iron fist inside its velvet glove.”33 This student-led uprising upends the megadonor-funded (see: Genocide Gentry, NYC Cultural Institution Index, etc.), institutionally backed normalization efforts of violence against learners, against communities.

Gestures toward solidarity (banner drops, marches, wheatpastings and murals, teach- ins/outs, etc.) across the world are seismically shifting the global discourse on Palestinian liberation and Indigenous sovereignty all while demonstrating that another university is possible. Social media campaigns, such as the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) Movement’s “#BoycottIntel” (No Tech for Apartheid, No Tech for Genocide), clarify for broad audiences:

Intel’s brand, which rests on the claim that it makes “technology that can enrich the lives of every person on earth” and shapes “technology as a force for good,” is tarnished by its fanatic ideological commitment to and deep complicity with an apartheid state that is perpetrating the first live-streamed genocide in history.

The insistence by the senior management and board of directors of Intel to invest in an apartheid state that the World Court has decided is also involved in plausible genocide in Gaza incriminates the company for complicity in war crimes, crimes against humanity and possibly genocide, exposing its betrayal of its own internal policies regarding global human rights. This insistence potentially incriminates them as individual decision makers in such crimes as well, according to international law.34

In June 2024, Intel’s $25 billion expansion of the Kiryat Gat manufacturing plant, for Fab 38, was postponed—marking a major BDS victory. In August, Intel’s stock price tanked and rumors spread that widespread layoffs could affect all rungs of the company’s ladder.35 By November 1, S&P Dow Jones Indices reported that Intel lost the spot it had held for twenty-five years on the Dow Jones Industrial Average to Nvidia. While none of this should be diminished, noticeably absent from many infographics and reposts online is the very active and ongoing destruction incurred by Intel’s operations, compounded by unrelenting acts of violence36 perpetrated by settlers across the Naqab, and all of Palestine. BDS is the floor, never the ceiling.

How many 100-year-old saguaro cacti, our elders, have been slain, uprooted (forced displacement!) to pave way for more Ocotillo campus?

The Arizona Israel Technology Alliance (AITA), a nonprofit established in 2018, is dedicated to strengthening and promoting investment, entrepreneurship, technology, business, and trade relations between the state of Arizona and Israeli companies. In 2022, it facilitated a $5 million grant through the BIRD (Israel-US Binational Industrial Research and Development) Foundation awarded across Arizona State University and Ben-Gurion University, focused on cybersecurity for “clean” energy products and services.37

The AITA’s website, under the tab “Israeli Ecosystem in Arizona,” features a geographically ambiguous image at its top: a two-lane road winding through dryland scrub, flanked by fencing with barbed wire. The ambiguity is purposeful: a shared topography with an occupying entity’s walls. We could be looking at the Gila River Indian Reservation’s boundaries with Chandler, with Intel’s Ocotillo campus, or at a highway cutting through Jabal al-Khalil in Palestine. Regardless, more walls, fencing, staged construction equipment, contracts-in-queue, federal statutes signal to the shareholder: business is booming.38

The desert’s principal decision-makers pulverize the fragile Sonoran ecology in the interest of centering the whims of zionist settler colonial desires; for profit, for land theft, for collusion between its universities and schools with R&D-as-dispossession. What the Arizona Commerce Authority deems a “pro-business environment”39 is in practice a web of legislation that includes very loose corporate regulation, low corporate tax rates, and a 2016 law banning state entities from entering into contracts with businesses who participate in boycotts of Israel.40 This anti-boycott law was amended in 2022 “to include public universities and community colleges in the definition of ‘public entities,’ that are prohibited from investing in or entering into contracts with companies that boycott Israel or territories occupied by Israel.”41 The legislation ostensibly prohibits researchers, students, staff, and faculty at Arizona schools from engaging in BDS campaigns against the so-called defense contractors and tech corporations that fuel forever wars and keep these universities fiscally afloat. (So, insert here the Next Great Executive Order, in the windfall of post-inauguration Project Esther–informed turmoil.)

It isn’t enough to share the call—Boycott Intel—because Intel’s hydra has implanted the 1-millimeter thick, 30-layered semiconductors into seemingly every conduit of convenience; silicon wafers—made by magnesium and sand through exothermic reaction—not only run all computers but create the very images we consume. Our vision is structured, in a sense, by this $681 billion (and counting) industry.

How, then, do we co-envision a way out, a way beyond, the technological prowess and predation that seemingly structure and circumscribe every aspect of our lives?

In April 2023, in a press release titled “Saving the Desert with AI and Drones,” Intel announced a program to target the “invasive” buffelgrass species throughout the Sonoran Desert.42 In collaboration with the McDowell Sonoran Conservancy, Intel drones are scouring the 30,000-acre preserve in Scottsdale, Arizona, to eliminate this “environmental threat,” producing high-resolution imagery of the low-desert scrub. Granted, the grass—initially brought to this desert in the 1930s as cattle forage—is a leading cause of brushfires across the region, but this is a stark reminder of how the more-than-human that finds ways to thrive in this landscape cannot wholly evade surveillance and capture.

As the press release notes, “Intel engineers developed an AI algorithm that quickly detects unique features of the plants, including their color, distribution, shape and density.”43 Masquerading as “beneficial,” this technology is at once bio- and necro-politically reordering the landscape. Here, through the algorithm, we can sense a greater connection between Sonora and Palestine; between the “smart shooter” AI-powered guns now regulating movement on Shuhada Street in al-Khalil and, for instance, the US Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory Rapid Capabilities Office (MCRCO) and US Naval Surface Warfare Center utilizing the Smart Shooter SMASH 2000 system for “test and evaluation” to “support their mission”;44 between the stun grenades, sponge-tipped bullets, tear gas, and myriad other remote-controlled weapons that border and order Palestinian movement, life, and empower the US/IOF and its tech-giant colluders to inflict harm, death, on the land and its Indigenous stewards. We can consider, for example, cloud-seeding operations to enhance rain as literal and figurative nonconsensual penetration of the zionist settler colonial agenda into the more-than-human realm; “Blue Wolf,” “White Wolf,” “Arbel,” Pegasus, Lavender, Graphite, and Project Nimbus exemplify zero-click predation and cloud-computing systems that “[centralize] Israel’s surveillance technologies into an all-encompassing cloud solution that can be used for ‘facial detection, automated image categorization, object tracking and sentiment analysis.’”45

We recognize the mis/management of bodies, of grass, of databases in the service of death-making—and we must also think of “redevelopment” and investment (whether via Pinui Binui or the CHIPS Act, etc.) and “cultivation” as a coordinated arm of destruction and occupation. We know the deserts are not empty; yet they continuously eradicate its beauty and determination, foolishly and hastily rebuild, poison it—by planting, by pest- and herbicide—and declare its capture a triumph.

In collaboration with MIT’s “Sensible City Lab,” Purdue University and Google created the “Tree-D Fusion” system, merging AI and tree-growth models with Google’s Auto Arborist data to create the first-ever large-scale database of 600,000 “simulation-ready” tree models across North America.46 Intended to “address” climate change and its ripple effects for urban forest management, marketing for this “dynamic tree modeling” spotlights lush areas in Jaffa, Palestine. Captioned as “Tel Aviv,” this simulation further spatially, cartographically, politically, and culturally erases Palestinian Indigeneity from the land. This current project, of course, is but another chapter reproducing the JNF-KKL’s 120+ year mission,47 an ongoing process of theft and destruction, and never a singular event.

Settler colonial agricultural/land management/extractive practices spanning centuries—first and foremost for the maximization of profit—a violence spanning continents—prove so inherently flawed and detrimental, they beg ecological/cultural exploitation and degradation touted as “solution.” This pernicious cycle reminds us: returning the land to its Indigenous stewards, for full, unimpeded sovereignty, is the only practical present- and future-oriented solution.

How many trees still stand at this very moment across Gaza? How many nopal (prickly pear cacti) have been bulldozed and/or bombed in the eighteen-plus years of its besiegement? And what of those removed from Indigenous land across the Sonoran Desert? To be against genocide and against occupation is the crux but also only the bare minimum here. It is about unlearning, learning, seeing, visualizing, aligning, coconspiring, rearranging our infrastructures and our lives in a way that centers Indigenous sovereignty; The Right of Return, Land Back.

It is about clogging the school-to-military contractor pipeline, about blockading and severing the flows of capital that prop up dispossession, “redevelopment.” It is about reading and identifying these spaces we move through as architectures solely in the interest of prolonging violence, from their place-names to ports and byways. And they can no longer hold. We must keep up; new worlds are being built. Adam HajYahia insists:

We must not mistake Palestinian return as something that will occur in the future. Rather, it occurs and has been occurring throughout this present moment to enable a future—a future that escapes the economic speculation of racial capitalism into an indeterminate future that isn’t yet molded, one that could be retrieved, that could be emancipated from colonial financialization.48

The ocotillo, not a kitsch name for the colonizer’s campus but as shelter. Melhok ki. As the million-bodies-long line headed north49 along Salah al-Din, a great return home. A succulent’s seed, germinating despite drought. Toufan al-Ahrar, Toufan al-Awda.

-

Natalie Diaz, “The First Water Is the Body,” Postcolonial Love Poem (Graywolf Press, 2020). ↩

-

Chris Markham, “Chandler's Upscale Growth Tied to Intel,” East Valley Tribune, July 31, 2005, link. ↩

-

Intel Arizona, “Community Investment Report, 2023–2024 Impact,” link. ↩

-

On May 5, 2014, pipes severed by construction crews at Intel Corporation’s Ocotillo Campus plant exposed 12 people to toxic ammonia. See Brandon Quester, Lauren Gilger, and Maria Tomasch, “2.8 Million Arizonans Live Within Vulnerable Zones from Toxic Chemical Leaks,” Arizona Capital Times, June 3, 2014, link. ↩

-

Markham, “Chandler's Upscale Growth Tied to Intel.” ↩

-

“Making the desert bloom” is mythology central to the zionist settler colonial project; the insistence that the land of Palestine, particularly in the Naqab, was historically a “land without a people,” empty space awaiting Jews to cultivate, beautify…profit from… There is no shortage of oral and written documentation, as well as what’s to learn from the land itself, dispelling this farce. We can learn about agricultural practices, centers of commerce, community practices, recipes, and so much more that testify to Palestine’s abundance, pre-colonization, from sources such as Walid Khalidi’s All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948 (Institute for Palestine Studies, 1992); Salman Abu-Sitta’s Atlas of Palestine (1871–1877) and (1917–1966); as well as Palestine Land Society and Palestine Remembered. ↩

-

This brings the company’s forty-year total investment in Arizona expansion to over $50 billion. For more, see Intel, “Intel Breaks Ground in Arizona,” link. ↩

-

The White House, “FACT SHEET: President Biden Announces up to $6.1 Billion Preliminary Agreement with Micron Under the CHIPS and Science Act,” April 25, 2024, link. ↩

-

The White House, “Remarks by President Biden on Agreement with Intel for CHIPS and Science Act Award,” press release, March 20, 2024, link. ↩

-

“CHIPS for America,” National Institute of Standards and Technology, U.S. Department of Commerce, link. ↩

-

CHIPS Communities United and Sierra Club, “Coalition Urges Caution in CHIPS Act Award to Intel,” press release, March 20, 2024, link. Noteworthy, too, are Sierra Club’s “educational trips” to Israel, not dissimilar from the Birthright Israel zionist settler colonial enterprise. For more, see Michael Arria, “Status of Sierra Club ‘Greenwashing’ Trips to Israel Unclear After Backlash from Activists,” Mondoweiss, March 15, 2022, link. ↩

-

For more on the Faluja Pocket, see Henry Norr, “The Nakba, Intel, and Kiryat Gat,” Electronic Intifada, July 23, 2008, link. ↩

-

Meron Rapoport, “Gov’t Contract Shows How Israel Enlists Forests to Grab Land from Bedouin Citizens,” +972 Magazine, September 22, 2022, link. ↩

-

“Joint Action Alert: Intel Support of Israeli Ethnic Cleansing,” Miftah, link. ↩

-

A persistent reminder: one person’s “defense” is another’s invader; a “War of Independence” is a Nakba–catastrophe. For more on this, see Rabea Eghbariah, “Toward Nakba as a Legal Concept,” Columbia Law Review 124, no. 4 (2024): 887–992, link. ↩

-

On “low carbon,” “ecologically responsive,” and “enhance the liveability,” see Andreas Malm, The Destruction of Palestine Is the Destruction of the Earth (Verso, 2025). ↩

-

“NexCITY - Refigured Urbanism for Kiryat Gat 2025,” MIT School of Architecture & Planning, link. ↩

-

“Absentees’ Property Law,” Adalah: The Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel, link. ↩

-

“Law of Return,” Adalah: The Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel, link. ↩

-

Patrick Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (2006): 387–409. ↩

-

As Mohammed El-Kurd pens in Perfect Victims and the Politics of Appeal, “Zionism is best defined by its material manifestations—Zionism is what Zionism does.” (Haymarket, 2025), 91. ↩

-

Examples are abundant–including on August 19, 2024, when representatives from the Intel Corporation toured Batan al-Hawa, Silwan (occupied Jerusalem), under the protection of heavily armed Israeli police. As described by the group Ir Amim on X (August 20, 2024): “We heard the police describing a neighborhood where Israelis and Palestinians share daily life and the municipality invests in the residents’ wellbeing–an image far from reality, in which Palestinian families are being evicted from their homes, and settlers are [taking them over]. It’s not clear why Intel is touring the neighborhood, or why they choose to do so with the police. What is clear is that the police’s rhetoric is very similar to the narrative put forward by Ateret Cohanim, the settler organization behind the evictions in the neighborhood.” ↩

-

“‘Universities are complicit in Palestinian unfreedom’ w/ Maya Wind,” Makdisi Street, YouTube, June 5, 2024, link. ↩

-

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Social Action Coordinating Committee records, MIT ArchivesSpace, link. ↩

-

Immanuel Maurice Wallerstein and Paul Starr, The University Crisis Reader (Random House, 1971), 240–243. ↩

-

For more, see Akela Lacy, “MIT Shuts Down Internal Grant Database After It Was Used to Research School’s Israel Ties,” The Intercept, January 16, 2025, link; Nora Barrows-Friedman, “Exposing Ties Between MIT and Israel’s Army,” Electronic Intifada, January 4, 2025, link. ↩

-

It is worth noting that the MIT-Germany Lockheed Martin Seed Fund, which promotes “the exchange between faculty and students at MIT and at universities and public research institutions in Germany,” is still very much active. See link. ↩

-

This fist is continuously rearing: February 17, 2025: Columbia President Katrina Armstrong meets with Israeli Minister of Education Yoav Kisch to expand ties with Israeli universities, link; February 21, 2025: Barnard College expels two students for their alleged involvement in classroom disruption, link and link; February 24, 2025: Former Secretary of State and CIA Director Mike Pompeo is hired as Columbia SIPA Institute of Global Politics faculty, link. ↩

-

Palestinian BDS National Committee, “Apartheid Chip – Boycott Israel,” March 19, 2024, link. ↩

-

Robert Hart, “Intel Shares Freefall as American Chipmaking Giant Careens Toward Worst Day Ever,” Forbes, August 2, 2024, link. ↩

-

Noteworthy active and ongoing destruction, particularly across Kiryat Gat, is the expansion of Israel Weapons Industry’s (IWI) manufacturing facility. This Israeli firearms company, founded in 1933, is one of the world’s top sellers of semiautomatic, assault, and sniper rifles. IWI anticipates completing its move from Ramat HaSharon into the Kiryat Gat site this year. ↩

-

See the BIRD Foundation’s interactive project database to search by region/sector to further connect these constellations of US–Israel “research & development” collusion: link. ↩

-

From Max Porter’s “Wild West” soliloquy (Palestine Festival of Literature, December 2023): “Business is booming. It’s an evil easily measured in mourning, the size of this world. We become one another. We who have spoken with the tongues of arms trade websites and .gov diktats and tech fair sound bites and Hansard-bleached Westminster gossip and those who have locked on, or given up, or never cared, or don’t yet know, or look another way, or only just found out, and feel it’s a bit late to say anything now anyway.” ↩

-

For more, see Palestine Legal’s “Legislation” overview for Arizona, specifically HB 2617 as amended by SB 1167, updated January 19, 2023, link. ↩

-

Palestine Legal, “Legislation.” ↩

-

Intel, “Saving the Desert with AI and Drones,” press release, April 20, 2023, link. ↩

-

Intel, “Saving the Desert with AI and Drones.” ↩

-

Arie Egozi, “Backed by Army, Smart Shooter Now Looks to Sell Counter-Drone Tech to Marines,” Breaking Defense, October 13, 2021, link. ↩

-

For more, see Carma Estetieh, “Israel’s Push Towards a ‘Frictionless’ Occupation,” Euro-Med Human Rights Monitor, October 3, 2022, link; Tech for Palestine, link; and No Tech for Apartheid, link. ↩

-

Karen Kloosterman, “AI Scientist Gets Full Map of Urban Trees Using Google Street View,” Green Prophet, November 13, 2024, link; Rachel Gordon, “Advancing Urban Tree Monitoring with AI-Powered Digital Twins,” MIT CSAIL, November 21, 2024, link. ↩

-

Al Wah’at Collective, “صَبْر – ‘Patience’ as Resistance,” Avery Review 69 (2024), link. ↩

-

Adam HajYahia, “The Principle of Return,” Parapraxis, 2024, link. ↩

-

The journalist Anas Jamal on X (January 26, 2024): “We are the owners of this land and we will not leave رغم القهر والألم والتجويع والخذلان غزة,” link. ↩

Taylor Miller—researcher and writer based in Tucson, Arizona—is an editor at large at The Avery Review. A longtime Sonoran Desert dweller, she earned her PhD in Geography from the University of Arizona and holds an MA and BFA in Art & Visual Culture Education from the University of Arizona. She is a university lecturer and a research fellow with the London-based Corruption Tracker/Shadow World Investigations, documenting the violence of the global arms trade. She’s motivated by border abolition and cactus propagation.