This essay is based on a lecture delivered in Arabic on May 22, 2024, at Darat Al Funun, transcribed and expanded by the author.

There has long been a discussion about the name of the Naqab. We were deliberate in refusing to call it “the Negev,” instead insisting on “Naqab” as a way to reclaim the land’s Indigenous identity. However, we were later cautioned by Dr. Salman Abu Sitta that even “Naqab” is a name imposed by conquerors, while the native term has always been Diar Be’er al-Saba. Despite this, we have chosen to embrace “Naqab” because, over the years, it has evolved into a term of empowerment—one that has helped raise awareness for the southern part of Palestine, home to fifty-four Bedouin villages whose histories and struggles deserve recognition.

Here, I would like to focus on embedded spatial values and why they matter so much—not only for me, as someone who was born here, but for most of us who care about finding alternative ways of living autonomously, defying colonial rule. Whether as an architect or simply an interested observer, one can engage with the local movement working to preserve these villages while learning from the values they embody—human values that translate into collective values and, ultimately, into the way space is organized.

Our villages have been shaped by oppression and are forced into an existence sans “formal” recognition. The villages’ presence is denied by the very government that controls the people’s land—an active, ongoing invisibilizing and delegitimizing of these sites, their architectures, and their people. However, rather than delving into the complexities of this oppression or attempting to make sense of it, I choose to focus on what does exist in these villages—their spaces, their social fabric, and the ways they have been built and sustained. Oppression is only one part of the equation, and as an architect, it must be considered, but not at the expense of recognizing the richness and ingenuity embedded in these places.

Here, the village of Beer Al-Mshash, where a cemetery dating back seven generations stands as a powerful reminder to not get caught up in the shallow debate over land ownership. Many Israeli scholars and practitioners may try to engage you in such discussions—but we needn’t fall for the trickery.

I was born in the Naqab, in a village called Al-Lagiyya, right on the edge of what the authorities recognize as a village and what is considered by forces as an empty open field—where Indigenous communities are denied the right to exist, to thrive. A hasty blue line, drawn by a foreign hand, determines whether you have the right to attend university or not.

The division of Al-Lagiyya is emblematic of the brashly divided Naqab, a partition of an “unrecognized” and “recognized” region. Recognition… by whom, for whom? At whose cost, for whose agendas and desires?

When invited to act, plan, and design in architecture, we must first question this rapid and unsettling transformation. What did the current agenda bury? What is it hiding? And what of its future iterations? These questions must be addressed before intervening in the existing spatial systems and social structures.

The one good thing about this division—in the “unrecognized” areas—is an absence of the state’s strong arm and how it leads to the preservation of our desired open life in most villages, even if material and spatial conditions attempt to convince you otherwise. This freeing, this freed land, is a counter-reading of forced enclosure, an existence within and beyond their borders. Seeing space in such a way similarly freed my perceptions and actions; I align with the unrecognized local movement as it continually develops, with or without governmental services. With or without architects.

The term “village” itself has become our political tool for gaining recognition, and understanding our fraught relationship with all its complications. Originally, we referred to our various settlements on the eastern side of the Naqab as Bar—literally meaning “wilderness.” This word embodies the spatial values cherished in these areas. It contrasts with the term used by the government: scattered. While Bar describes the natural and geographical character of the land, “scattered” implies irrationality and disorder—a narrative repeatedly used to delegitimize the villages of the Naqab and justify their erasure.

Many understandings of the southern struggles are hidden within the words used in closed circles… at politicians’ tables… and in government laws. Something that took me a while to understand while working in this field is that when we speak about recognition, the Israeli government speaks about establishment. This distinction is crucial: while recognition should acknowledge and restore land rights and sovereignty, in practice, it often results in the opposite—reducing ownership to a fraction of what once existed, reinforcing state control rather than true acknowledgment.

Architecture, as I studied it at Bezalel, was a means of making things look more appealing—comfortable to the eye, inviting. But in the villages, this approach felt irrelevant. How can we expect aesthetic considerations to take precedence for 150,000 residents living in a landscape of struggle, shaped by decades of displacement and deepening poverty? Yet, despite seemingly insurmountable obstacles, many conversations among land defenders emerged—seeking dignity, functionality, and resilience in the face of erasure.

Here, I won’t bring in quotes by David Ben-Gurion calling upon young, eager zionists to accept the “real” challenge of blooming the desert. Nor will I turn this into a historical timeline detailing the abrupt challenges that have reshaped the Naqab in less than fifty years—ongoing to the present day.1

Instead, I will try to point out.

An artist from New York, Zaid Arshad, once taught me the power of pointing at things rather than merely describing them—a method I would like to try here. Rather than recounting the well-documented injustices or tracing a familiar historical arc, I will attempt to bring attention to the details often overlooked, to the spatial and social realities that shaped the spaces we witness today in the Naqab.

As children, we played a game where one of us would scream bar! (wilderness), and we would all jump to one side. Then, they would shout bahar! (sea), and we would leap to the other.

The inhabited Naqab, mostly the northern part of the southern triangle of the territory, used to be called Bilad Gaza. We could say that the eastern side of the Naqab was bar—dry land and open, wild grazing fields—while the western side could be referred to as bahar, meaning the sea, but more precisely, the wet agricultural lands of the Bedouin tribes. My grandfather Amer Al-Sana used to own agricultural lands close to Gaza.

The first thing Israel did in the Naqab during the Nakba was to empty the west—either by expelling its inhabitants into exile from Palestine, or forcing them eastward. Imagine what this does to a human being—to steal the water, the greenery, the very essence of life from the land’s people.

This, in my eyes—which are sometimes criticized as overly emotional and too spiritual—was the first spatial (and cartographic, architectural, etc.) decimation of this region; it transformed a once familiar and varied landscape into a single, confined space.

To this day, families visit their lands in the west—connecting to them, recalling their past, or simply enjoying the breeze that carries the scent of what once was. They send their wishes through Wadi Gaza, a stream that originates in Hebron, flows through Be’er al-Saba, and makes its way to the sea.

From 1948 until 1970, the remaining families were policed under military rule, prohibited from building anything and forbidden from grazing black goats2—the very source of Beit Sha’ar, which was, in essence, a home made of goats hair. This had two profound impacts on the spatial organization of Bedouin neighborhoods.

The first of these was the freezing of movement. For Bedouins, the inability to move is a death sentence—not just for the people but for the land, the shrubs, and the herds that depend on seasonal migration.

The second impact was seen and felt in the way people began to build. With Beit Sha’ar no longer an option, they turned to whatever materials were available, as long as they were not wood, concrete, or metal—materials explicitly restricted by the occupying forces. Despite these restrictions, the different tribes continued to expand their presence, and this troubled the Israeli authorities—an anxiety dealt with by the “Seven Townships” plan3 and the Israeli Planning and Construction Law of 1965.4

Their premise was simple: concentration and control. In a very short period of time, the Naqab experienced rapid, violent, and incomprehensible transformations, affecting the collective consciousness of its Indigenous population regarding the concept of the house, how the neighborhood should be built, and even the meaning of identity itself. Many homes began to have empty rooms, reflecting emptiness and the loss of identity and social fabric.

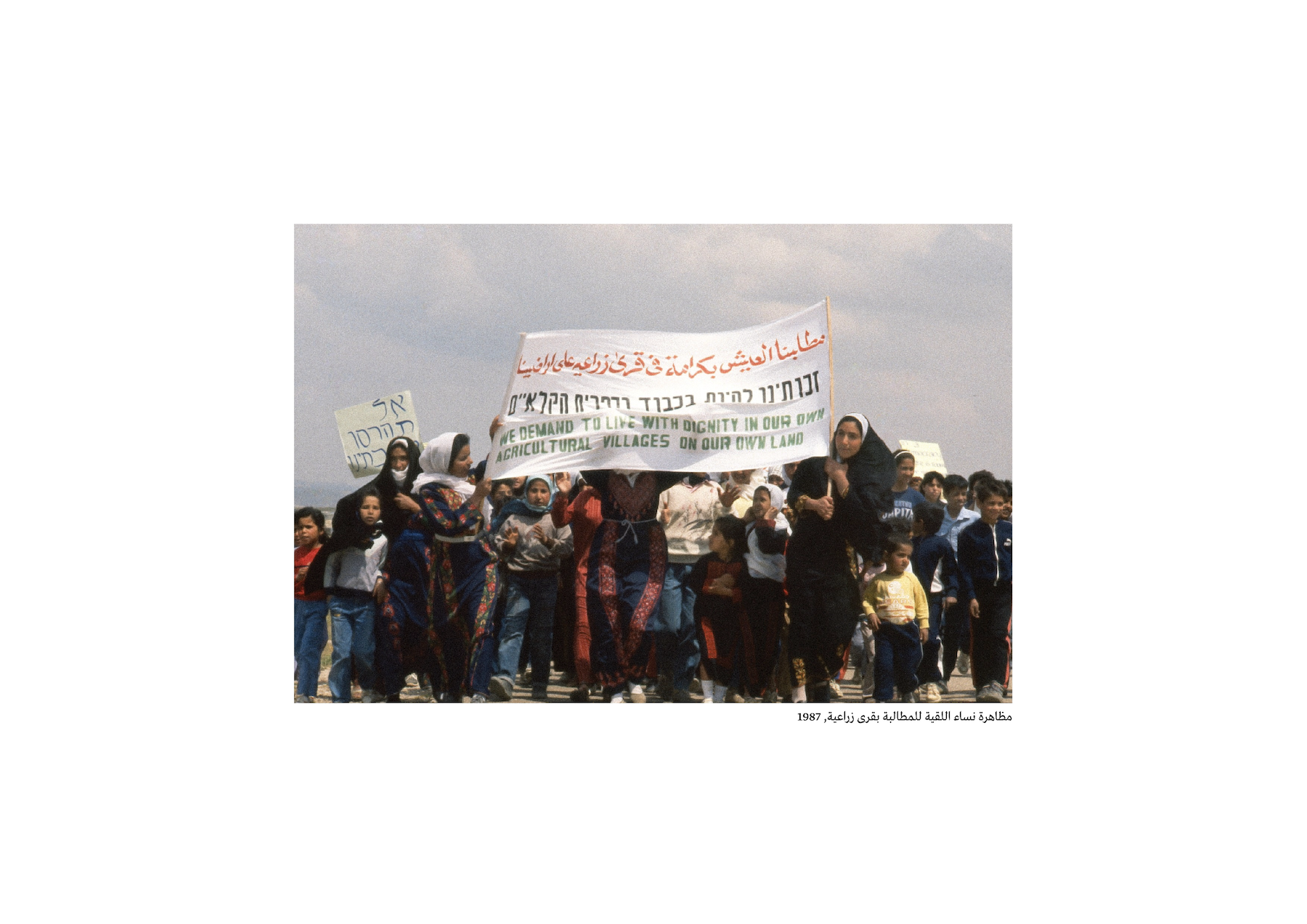

Most of the townships were built only in the late 1980s, and the sociopolitical movement demanding the right to agricultural villages began to take shape. Tonight, while writing, I stand on the side—of this iteration of partition—as someone who grew up in one of the seven newer townships—spaces of total social devastation of ethics—only to watch, witness, learn from the thirty-seven unrecognized villages encompassing everything we lack.

At the end of 1994, the regional master plan for the Southern District, TMM 14/4, was submitted. The plan’s provisions stated:

The principles of the plan for the Bedouin sector include the continued settlement of the Bedouins in the seven existing townships, expanding, densifying, and developing them as urban and semi-urban settlements.5

In other words, the plan upheld previous policies denying any planning solutions for dozens of Bedouin villages with a rural agricultural character. All the while, the Israeli Green Patrol not only continually forbids Bedouins from grazing black goats but also prevents people and their kin from living on their lands altogether. For decades, the patrol has uprooted communities, confiscated and discarded their belongings, and forced people to follow their possessions into exile. It has planted trees instead of constructing homes as a means of territorial control, further erasing traces of Bedouin existence.

This perspective is at once endemic and parasitic; it is also reflected in the metropolitan master plan, where vast areas are painted in different shades of green—marking them as either developed or planned landscapes for future projects. However, these so-called future-oriented landscapes actively erase historical villages, rendering them invisible on planning maps while treating them as obstacles rather than communities with deep-rooted histories.

I truly believe that everything starts from a personal place. My writing comes from a personal place—from a need to be heard, from a need to have companions and partners in this work. To consider architecture in the villages today is suicidal: to operate in a space where one is not meant to operate, to build where one is not supposed to build, and to envision and create spaces that may ultimately be demolished.

Yet I cannot think of any act more important than this.

To stop waiting. To seize the moment. To begin finding alternative physical solutions that can promise families safe and dignified lives.

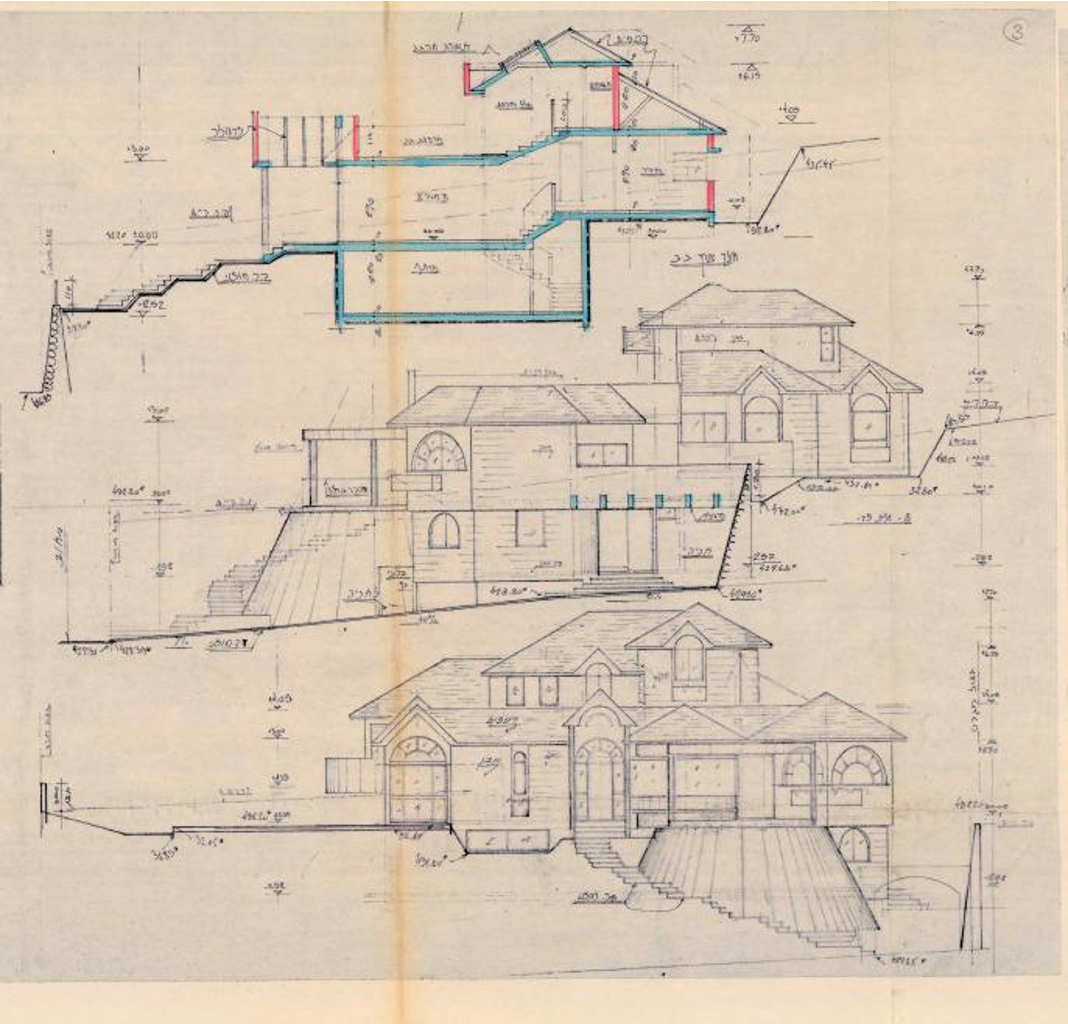

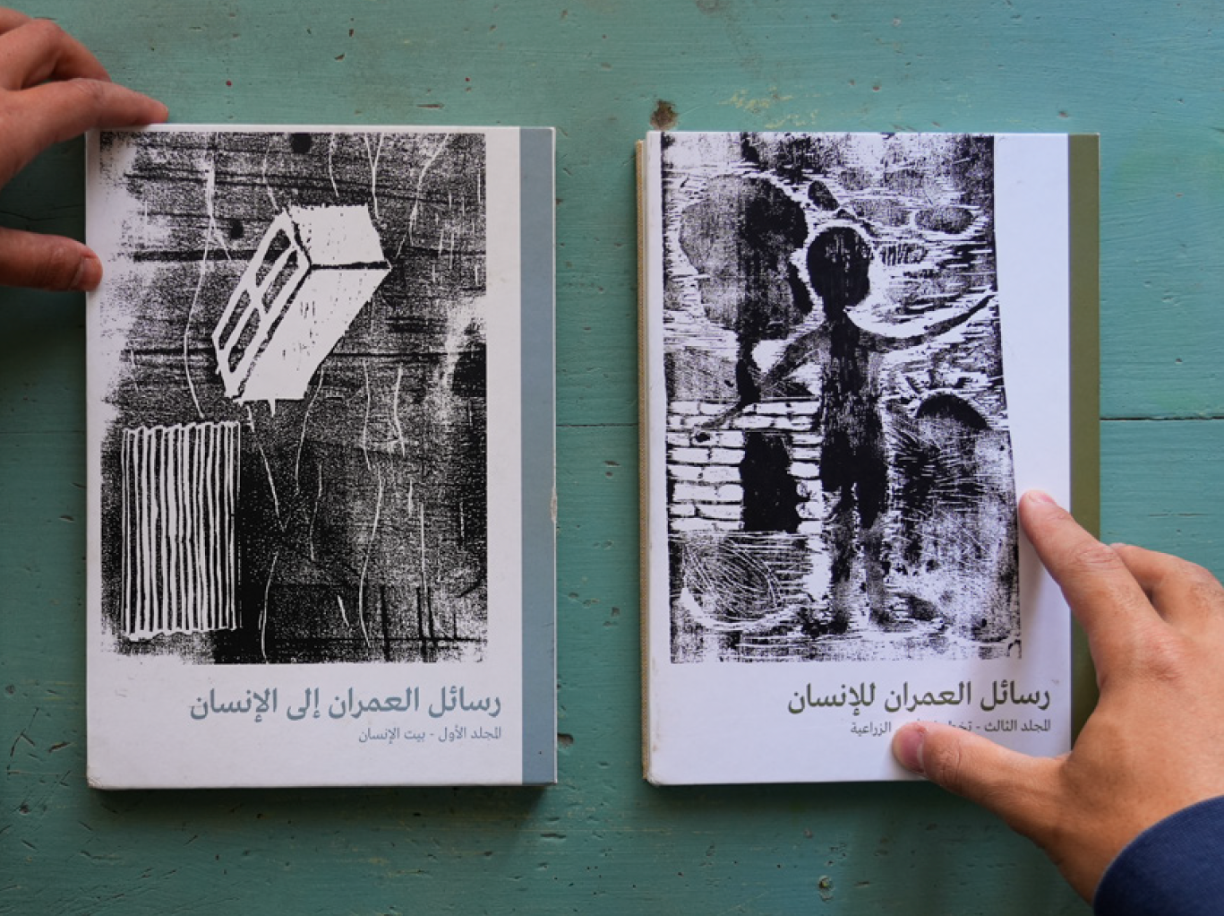

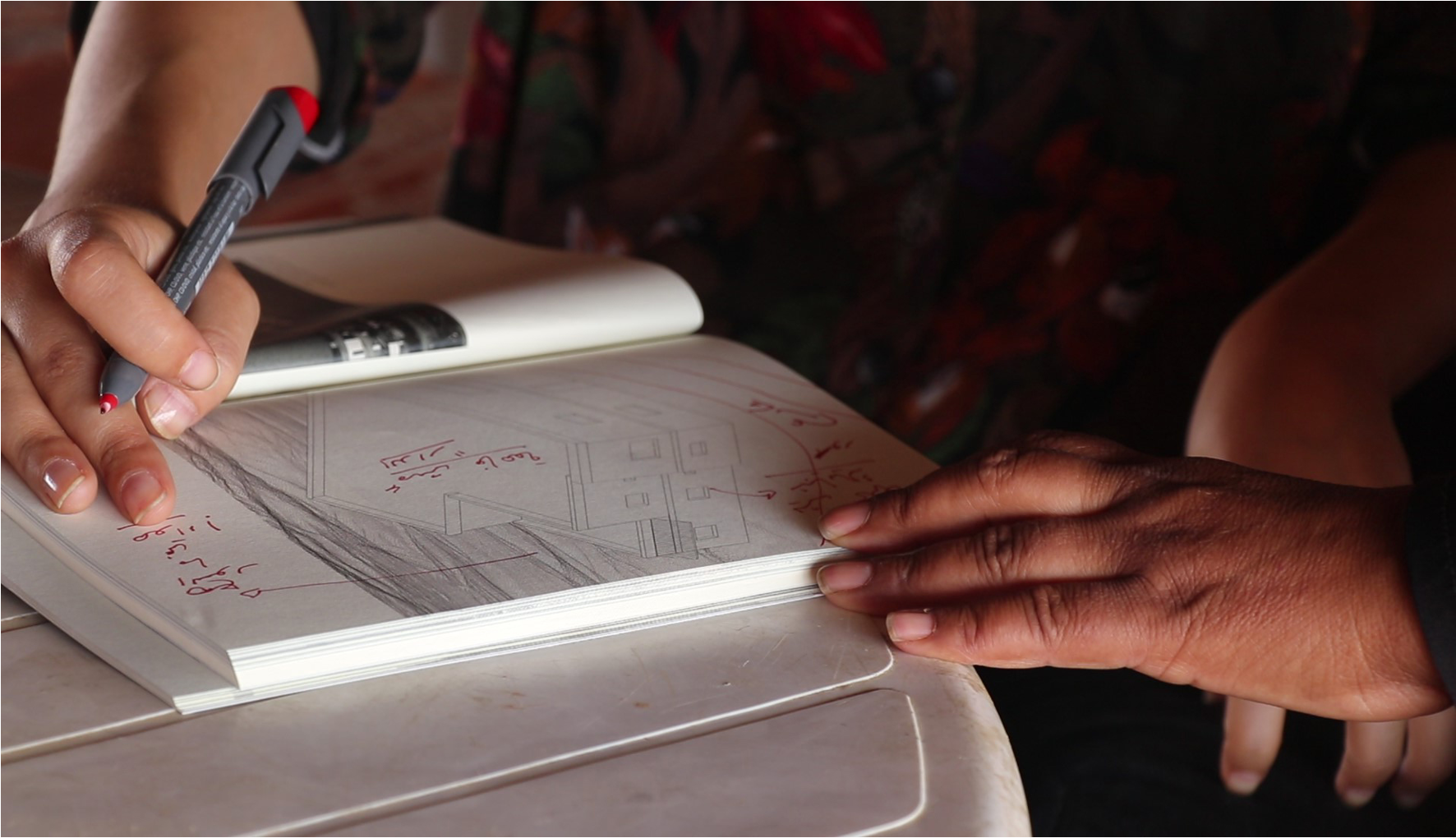

My first attempt at this reclamation, while studying in Jerusalem, was to write letters. I wrote letters about the house, the neighborhood, and the agricultural land. Each letter recalled homes from our poems, examined existing structures, and proposed affordable new typologies—different in their structure, materials, and cost. Imagining this might spark an intimate discourse within the circles I work with, eventually leading to real attempts and actual construction on the ground.

Today, while continuing to explore possible local structures and material usage through a laboratory I built with Haytham Canaan at his farm, Nabat, in Tamra, my focus has shifted to putting the villages on the map. This is a life that should be valued and seen by anyone who chooses to look.

To do that, I started from the Be’er al-Saba’ Valley—an endless expanse of villages where you cannot tell where one ends and the next begins. They flow seamlessly with the natural streams and hills, forming a continuous landscape of Bedouin life.

While making this map, we visited sites with landmarks existing since pre-1948 through the present day and discovered stories and sites that had been demolished. This is extremely important as we contextualize the Naqab—as many people know demolition more than they know construction.

We’ve discovered traces of water routes that were demolished, and this was visible only through direct surveying. We examine the complexities of surveillance and whether our work ultimately serves the oppressor or the people. This raises critical questions: Are we, as architects and planners, serving the interests of our people, or are we inadvertently assisting the occupation? We need to be realistic and approach this issue with caution. We must openly question how we handle this information, what we choose to share, and in what context.

Demolition has become a central topic in our lives, and sometimes, discussions around it carry a bleak sense of humor, even though this ordeal should never be normalized. Escalation in extremist acts this past year is visible in the massive uptick of forced demolitions and displacements across the region.

A provocation that arose during this initial lecture—what of the persistent demolitions in the village of Al-Araqib? I have heard that it has been demolished over 300 times. Why such persistent targeting? What do the residents of Al-Araqib do after each demolition? Do they build new houses, or do they reconstruct the same homes? If the village has been destroyed 300 times, what drives them to keep rebuilding it?

The reason is that Al-Araqib has become a symbol of resilience in the Naqab. In each of these immensely brutal episodes, the authorities try to break this symbolism by demolishing it again (and again). Al-Araqib’s people refuse to leave their land, which is why the village is continuously demolished. In reality, they do not build permanent homes anymore because it is no longer possible—every small house or even a tent is demolished. Yet they keep returning. Resisting.

Over the past few years, they have developed new methods to remain on the land, such as sleeping in cars or constructing extremely lightweight shelters. Recently, though, even these cars and light structures have been demolished, making the situation increasingly difficult. As for constructing new houses, this is simply no longer an option.

Honestly, after hearing all this, I feel that the occupation does not just aim to control the land but also to systematically weaken the people. This is deeply painful. As a someone who tries to build a home—as a trade, and for my heart—I have a personal attachment to the space I create for myself; it becomes part of my identity. While open spaces are important, a closed space remains a place where one feels privacy, belonging, and safety.

How do you keep going after every demolition? How do you continue redesigning, researching, and engaging with those impacted, repeatedly? Do you start thinking about stronger building materials, or do you focus on designs that are quick and easy to rebuild?

Should the materials be durable, or should the design prioritize ease of reconstruction? As an architect, I try to design spaces with the awareness that they might be demolished one day, yet I always think of them as if they will remain—as if they will endure and coexist with the people. This makes the design process emotionally and intellectually challenging and exhausting.

What is the role of enclosed spaces? And what are the terms of the enclosure? Should they exist in specific locations? Will they eventually be lost? How do you decide? Do you aim to create the best possible solution, or do you strive for the strongest one? This is a deeply personal connection. How do you make these decisions?

This is a question I often ask myself. Whenever I work on proposals, I realize there is always more to consider. If an area faces siege, should it be designed to be light and easy to dismantle? There are available techniques, but understanding that a structure might be torn down affects planning—affects the psyche, the soul, the aspects of the land that are so much more than the paper and plan. Designing for potential demolition is a difficult consideration.

The first approach is to learn from Al-Araqib, where you stand firmly for justice. My mom would say, احزم أيدك عالصحيح، لا بتبرا ولا بتقيح, meaning: Hold on to what is just, and you will never fall ill—neither in mind nor in heart. To hold on to justice can mean accepting the ephemerality of your architectural actions and refusing to stop moving—either outwardly or inwardly.

I personally cope with these difficult days through different means of expression—using art to convey the terror we experience—we live, endure, survive—every day in the Naqab. Art helps me process the trauma of witnessing the erasure of a house I once knew from the landscape. This was the essence of the film I created with director Patricia Echeverria—Remember This Place.6

One must find their own way to protect their heart, not their career. For the heart is the source of our ideas, our intuition, and our care. Solutions do not emerge from thinking alone; rather, they arise from what we feel sincerely and deeply while being present in the places we work in. It is this raw connection that compels us to explore different means—means that we later call architecture so that the outside world will take notice.

-

For more on this history, see: Mansour Nasasra, The Naqab Bedouins: A Century of Politics and Resistance (Columbia University Press, 2017). ↩

-

“Palestine: In-Between, ‘The Black Goat Act’ w/ Rabea Eghbariah,” Lifta Volumes, June 25, 2021, link. ↩

-

Monica Tarazi, “Planning Apartheid in the Naqab,” Middle East Research and Information Project, 253 (Winter 2009), link. ↩

-

“Planning and Building Law, 5725—1965,” Adalah: The Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel, link. ↩

-

Bimkom: Planners for Planning Rights, מטרופולין באר שבע – תמ”א 23/14/4, link. ↩

-

Patricia Echeverria Liras, dir., Remember This Place: 31°20’46’’N 34°46’46’’E, link. ↩

Lobna Sana is a Bedouin architect and artist from the Naqab. Her practice is dedicated to addressing social and spatial challenges through architectural design and a multidisciplinary artistic approach that includes film, sculpture, mapping, curation, and activism. She holds a bachelor’s degree in architecture from the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem, where she was awarded the Azrieli Prize in Architecture in 2022.

Currently, Sana plays a leading role at the Regional Council for the Unrecognized Bedouin Villages in the Negev (RCUV), where she develops innovative local mapping methodologies and architectural solutions. Her ongoing projects include mapping the unrecognized villages from a local perspective and developing indigenous building techniques.